“[T]here is a provision in the McCarran bill, an unprecedented provision, section 212 (e), which would give the President of the United States the authority to bar any and all aliens, or any class of aliens, at any time the President felt such a move was required in the public interest. This is plain authority for the President to shut off all immigration, at any time, or to reduce it at any time, or to shut off immigration from any country, at any time, in time of peace as in time of war.”

That was Sen. Herbert Lehman (D-N.Y.) speaking on the floor of the Senate on May 13, 1952 in opposition to the provision of the Immigration Act of 1952 — now 8 U.S.C. 1182(f) — that has been invoked by President Donald Trump to temporarily suspend immigration from seven countries deemed to be terrorist hotspots.

That section of the law Lehman objected to, and remains on the books today, states, “Whenever the President finds that the entry of any aliens or of any class of aliens into the United States would be detrimental to the interests of the United States, he may by proclamation, and for such period as he shall deem necessary, suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrants or nonimmigrants, or impose on the entry of aliens any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate.”

Although an opponent to the measure, Lehman explained precisely and quite clearly what the extent of the grant of power to the president was under the 1952 law, as was originally understood by members of Congress.

The law was adopted overwhelmingly. President Harry Truman actually vetoed the bill, and the vetoes were overridden in the both the House and the Senate by the requisite two-thirds majorities. It was a popular bill.

The 1952 law put together a fairly strict scheme of national quotas limiting the number of immigrants that could be accepted on a per country basis.

As a matter of construction, then, the provision allowing the president to suspend the entry of any and all immigrants into the U.S. was a statutory exception to that scheme — when such a presidential proclamation suspending immigration from that country was in effect.

As Lehman emphatically noted, “This is plain authority for the President to shut off all immigration, at any time, or to reduce it at any time, or to shut off immigration from any country, at any time…” Again, “from any country,” even though the law otherwise allowed for a set number of immigrants to be allowed on a per country basis.

In effect, the president under the 1952 law could suspend the quotas of the affected nations via proclamation, and when said proclamation was lifted, the quotas would be reinstated.

During the debates on the law, both in committee and in Congress, there were many statements of groups testifying in opposition to this very provision of the bill, and they all read it the same way Lehman did, as a broad grant of power to the president to suspend any and all immigration, even in peacetime.

Congress even considered limiting this provision to only be invoked during a time of war or national emergency, a proposal Lehman endorsed in his floor speech — and that proposal was rejected by Congress, which ultimately left that part of section 212 unaltered.

When the Congress amended the nation’s immigration laws in 1965, it had every opportunity to remove this exceptional grant of power to the president or limit it. That never happened.

In fact, the American Legion testified on behalf of section 212 in testimony before the House Judiciary Committee in 1965, submitting for the record a resolution by that group that stated “the American Legion strongly supports the provisions of section 212 of the Immigration and Nationality Act pertaining to the security of the United States and the mandatory exclusion of undesirables, it therefore urges the retention of the mandatory exclusion of all classes therein defined so that the strength and security of the United States of America shall not be weakened in the years ahead.”

Section 212, including the presidential power to shut down the border to all immigrants in times when the president deemed it detrimental to the interests of the U.S., was left intact.

What the 1965 law replaced was the national quotas for more evenly distributed regional allocations from throughout the world, giving up on the decades-long preference for European immigration. It did include a non-discrimination clause, 8 U.S.C. 1152(a) that states “no person shall receive any preference or priority or be discriminated against in the issuance of an immigrant visa because of the person’s race, sex, nationality, place of birth, or place of residence.”

That is, unless the president has by proclamation decided otherwise to “suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrants or nonimmigrants,” presumably in exigent circumstances, as the law still allows.

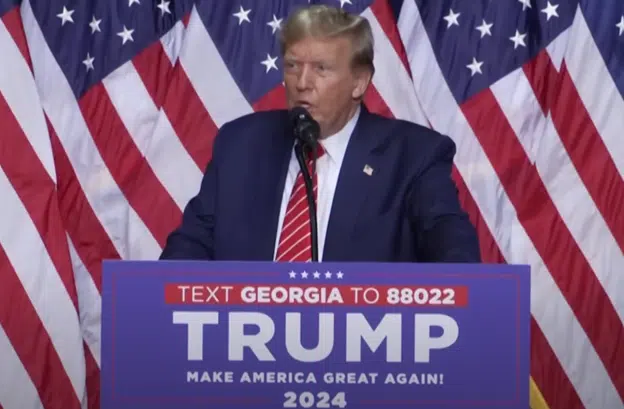

Which is exactly what President Trump has done, blocking immigration from the seven countries, for a 90-day period while the administration puts in place new restrictions on who may enter the U.S. and under what circumstances, as the president has the authority to do under the statute. Extreme vetting is on the way.

Under the law, Trump could go much further, shutting down the entire border if he wanted to, but he has limited the travel ban to short length of time, to be replaced by whatever the new policy will be.

By leaving in place and not overturning the president’s power to suspend any and all entry into the country, the 1965 law allowed that power to remain an exception to the scheme of regional allotments of immigration.

If there is any legal argument against Trump’s policy, it might be that the 1965 statute’s non-discrimination clause would block such a travel ban. And it might, if the 1965 law had removed the president’s power to suspend the entry of any and all immigrants, but it didn’t.

When there are two closely related statutes, they must be read consistently.

The president’s power to close the border remains an exception to the normal scheme of immigration outlined by law.

Interestingly, the statute in question was amended — in 1996 — to add an additional clause giving the Attorney General the power to shut down entry by immigrants on particular airlines that fail to comply with federal regulations: “Whenever the Attorney General finds that a commercial airline has failed to comply with regulations of the Attorney General relating to requirements of airlines for the detection of fraudulent documents used by passengers traveling to the United States (including the training of personnel in such detection), the Attorney General may suspend the entry of some or all aliens transported to the United States by such airline.”

Congress has had many opportunities to amend and limit or eliminate the 1952 grant of power, and if anything, its only action to date was to expand this section of the law in 1996, by giving the Attorney General to power to suspend an airline’s access to the U.S. if its detection of fraudulent documents is not up to snuff.

So, as a matter of law then, textually and based on the original intent of the 1952 law, the travel ban President Trump has instituted is on solid legal ground.

Constitutionally, there is practically no argument against the Trump travel ban. As an exercise of his Article II executive power to conduct foreign relations, shutting down the border in a time of emergency or a time of war is pretty much a no-brainer. Nor is there any constitutional right for non-citizens overseas to travel and immigrate to the U.S.

If courts uphold centuries of jurisprudence deferring to exercises of presidential power like this, often ruling that such actions are non-justiciable, it ought to stand up to judicial scrutiny. But everyone should also bear in mind that in less than 90 days, the travel ban may in all likelihood no longer be in effect, becoming a moot point very soon. What will come next are the new restrictions on travel to the U.S. that Trump under the same statute has the power to implement.

Then, the question will be on the list of counties promulgated by the Secretary of Homeland Security pursuant to the executive order that “do not provide adequate information” to adjudicate visas proving “that the individual seeking the benefit is who the individual claims to be and is not a security or public-safety threat.”

Again, the president can issue whatever restrictions he deems necessary on entry into the country under the law and the Constitution, including any necessary vetting, in pursuit of the government’s primary responsibility to protect and defend the country.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.