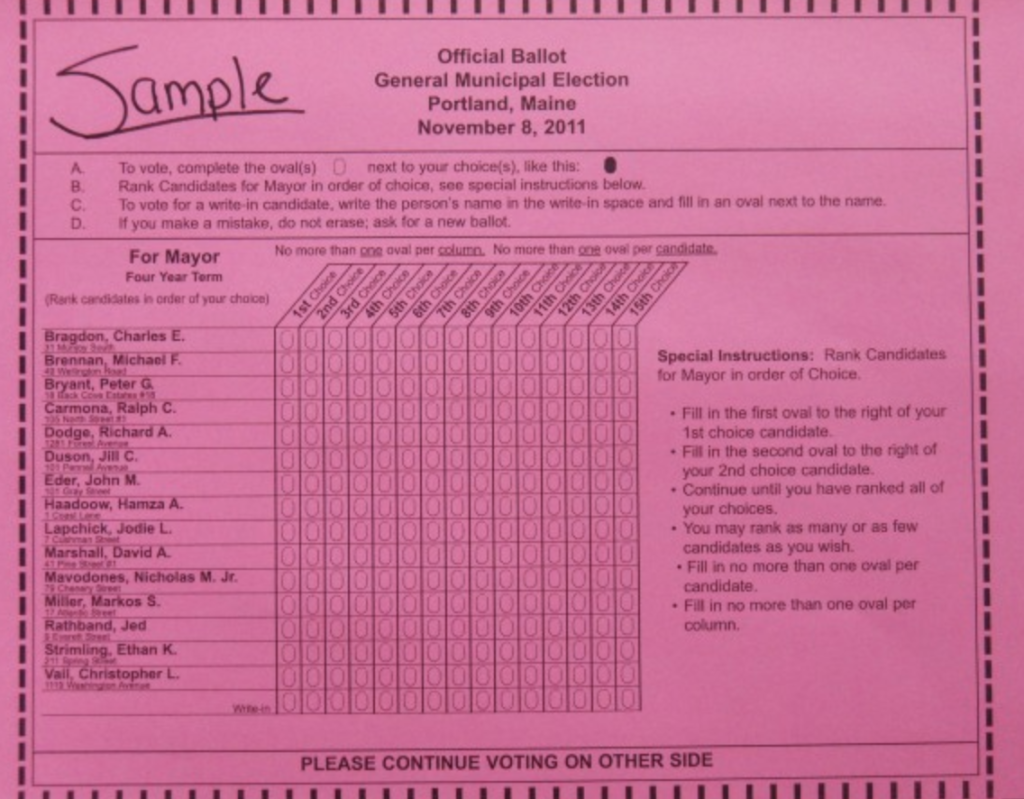

A left-leaning foundation is pushing a complicated election scheme called Ranked Choice Voting. Alaska recently adopted it in a statewide ballot initiative and policy experts say it could undermine faith in the election system.

Actual sample ballot of what Ranked Choice Voting election. The voting scheme leaves many voters confused and disenfranchised.

A left-leaning foundation funded and headed by a former Texas hedge fund billionaire and his corporate attorney wife is a leading backer of a controversial voting scheme known as Ranked Choice Voting (RCV). Between 2012-2017 the Laura and John Arnold Foundation spent nearly $45.5 million dollars pushing RCV, and other election “reforms” which will undermine election integrity and participation.

In recent years, the Arnold Foundation has succeeded in convincing voters in Maine, New York City, and Alaska to adopt the complicated new system. Massachusetts voters rejected RCV in a 2020 statewide ballot initiative.

Sarah Montalbano, a Research Associate Alaska Policy Forum recently sat down with American for Limited Government (ALG) to explain what RCV is and why voters should be concerned.

ALG: Voters in Alaska adopted Ranked Choice Voting in last November’s general election by the thinnest of margins, just half a percentage point. How does CRV work and what do backers claim it will achieve?

Sarah Montalbano: Ranked Choice Voting sounds like a really good idea until you start delving into the technicality. Under RCV voters are asked to rank the candidates from the most to least favorite. You put your first preference, your second preference, even third and fourth preferences. If there’s not a majority of first preference votes, then those are tallied up and the balance that listed the eliminated candidate, as their first preference, they go on to the second choice candidate. So if your first preference doesn’t win, in the first round, they check your second preference. If your second preference doesn’t win in that round, they check your third preference and your fourth preference and maybe even all the way down your ballot.

ALG: For some of us, the only thing we’ve ever heard about RCV was in the New York City primary elections last year. I just remember it was very confusing and I didn’t understand how a winner was finally determined.

Sarah Montalbano: It’s important to recognize that RCV was only one of several factors that led to problems in the NYC primary elections last year. New York City spent about $15 million on an education campaign to explain rank choice voting, and it still didn’t really work. A political analysis basically said that voters in South Bronx had a higher incidence of ballot mistakes. And that’s kind of the thing we see with rank choice voting is the complexity of the method makes it hard. It advantages the voters who have more time, interest, and ability to research and rank several candidates all at once.

ALG: Quoting from your guest column on RCV in the Washington Examiner,

Yet confusion is only one downside of ranked-choice voting. The most concerning aspect of it is that it disenfranchises voters through “exhausted” ballots, which occur when all the candidates on a ballot have been eliminated before the final round of counting. Proponents of ranked-choice voting contend that the number of exhausted ballots is small, but a 2015 study of more than 600,000 ballots in four San Francisco mayoral elections showed ballot exhaustion reaching 27%. In NYC’s Democratic primary, there were 140,167 exhausted votes, almost 15% of the total. When large percentages of voters in every election have zero impact on the outcome, faith in the legitimacy of elections is hard to justify.

Exhausted ballots lead to a sobering conclusion: Ranked-choice voting does not guarantee winners receive an absolute majority. In practice, it does the opposite: A study of 96 ranked-choice voting races by the Maine Policy Institute reveals that when you account for exhausted ballots, the eventual election winner fails to receive a true majority 61% of the time. Due to ballot exhaustion, ranked-choice voting only guarantees that the winner has the majority of all valid votes in the final round of tabulation, not a majority of all votes cast.

To underscore that point, in one election nearly a quarter of the voters were disenfranchised by the system.

Sarah Montalbano:Yeah, it’s really frightening that this is part of the process. This is a feature of the system, not a bug, as we say in computer science. One other thing I’d like to note is that because RCV is so confusing, there’s a lot of ballot errors that also disqualify those votes. You might try to rank only one person in which case if your first preference doesn’t make it to the rest of your ballot, you didn’t put anything so it doesn’t count. You’re just making mistakes that are going to throw out more ballots and we actually see a lot more ballots are discarded in RCV voting elections.

ALG: That’s outrageous. It undermines people’s faith in the election system and process and that’s one of the biggest problems we face right now as a nation after the 2020 election. There is a lack of faith in the integrity of the elections and so we see a lot of states moving towards the election integrity measures to give people more faith and confidence and that the system is transparent and that their vote counts.

And then you point out in your article that certain groups tend to benefit and other groups of voters are hurt by this.

Sarah Montalbano: RCV really advantages more educated voters and wealthier voters and people with free time and energy to devote to this. In the New York City primary we had 13 candidates and five slots. And when you do the permutation there’s more than 150,000 combinations that you could actually put these people and that’s a mind boggling amount of choice. And I think it really shows that there’s difficulty in actually implementing this because now instead of guessing, all right, I intend to vote Republican. So I know I’m probably going to like the Republican candidate. You can just pick that person but now you have to rank several Republicans or you have to write help Republicans and Democrats and independents and libertarians you have to do so many, so much research. I don’t see this helping voter turnout. We don’t actually see that helping voter turnout in any situation with rank choice voting.

ALG: Alaska got this through a statewide ballot initiative in November by half a percentage point. Who is pushing CRV and the where did it come from? Was this an outside group coming into Alaska?

Sarah Montalbano: There’s obviously a lot of Alaskans that support this but it’s really being pushed along by outside interest groups. And whether you are an Alaskan who agrees or disagrees with RCV, we don’t want outside interest groups affecting our internal affairs as Alaskans.

ALG: The left-leaning Arnold Foundation out of Texas has been behind a lot of the RCV funding. Is there a partisan component to RCV?

Sarah Montalbano: I think for a lot of Democrats, and people generally on the left, see RCV as a panacea for our democracy. They think it will fix so many problems with elections, like polarization, or, reduce the money in politics. And I don’t think any of those arguments really hold up. It doesn’t significantly change election outcomes from what they would have been under one person, one vote system. It doesn’t really ameliorate racially polarized voting. Voters can identify the ideologies or policies of the candidates under RCV and that dashes, hopes of a centrist coalition emerging.

ALG: For a lot of us, we just want to know, will RCV give us greater confidence in the election outcomes or will it improve democracy?

Sarah Montalbano:

I don’t think functionally it will. I think we’ve seen that voter turnout decreases. We’ve seen that confusion increases. There’s disenfranchised ballots everywhere. And it really confuses younger voters and minority voters. I think it’s very telling that the Arnold Foundation puts RCV initiatives under their democracy tab. They would like this to improve democracy. I just don’t think it does.

ALG: Thank you for sharing your expertise with us. I hope Americans will be on the lookout for RCV coming to their states.

Catherine Mortensen is Vice President of Communications for Americans for Limited Government.