“If [the Russians] want to collaborate and show they will properly act with us going forwards — so-called cyber norms — I think it’s a conversation our State Department is already having and one which started in previous administrations and that Trump should support that effort…”

That was U.S. Rep. Dutch Ruppersberger (R-Md.) on July 17 responding to an idea floated by Russian President Vladimir Putin for a joint U.S.-Russian task force to look at the Russian hack in 2016 of the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and John Podesta under the 1999 treaty on mutual legal assistance in criminal matters.

For Ruppersberger’s part, he rejected such a task force, that is, he said, “unless the President bluntly shows that evidence that Special Counsel Mueller put into plain English for him on Friday — must be addressed with Putin.”

Although under the treaty, it would actually be up to the Attorney General or his designee to work with the Russian Procurator General on a criminal case. In this case, it would fall under Special Counsel Robert Mueller and Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein as it relates to the attempted prosecution of a dozen Russians said to be GRU intelligence agents who hacked the DNC and Podesta and had the emails published on Wikileaks. If they ever want to try the case against the accused, it might be considered, since they will never be extradited to the U.S. for trial.

Leaving aside whether Mueller would go to Russia to interview the alleged hackers — President Donald Trump suggested Mueller would not want to go in a Fox News interview with Sean Hannity on July 16 — the overall idea of working with Russia to get to the bottom of the DNC and Podesta emails appearing on Wikileaks goes to the heart question of establishing international “cyber norms” in the words of Rep. Ruppersberger.

Ruppersberger suggested that this could somehow be accomplished by the State Department, citing the work of previous administrations. Although such an approach has hardly been effective, if we are to be honest about what’s been occurring.

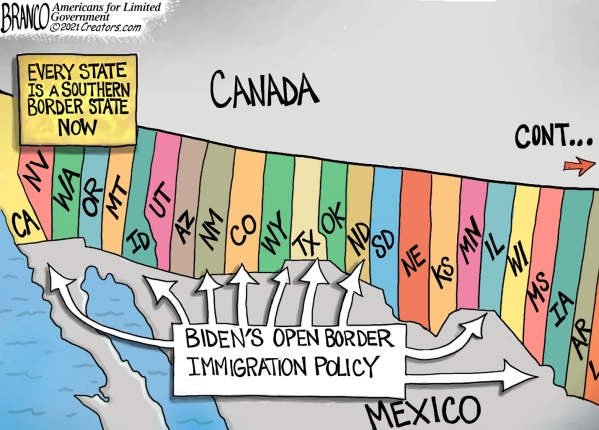

On just the question of election interference, in the past five years, Russia has been accused of intervening in the 2016 U.S. elections and Brexit and the U.S. has been accused of intervening in the 2015 Israeli elections and in Ukraine in 2014 and so forth. Generally, every major power in the world carries on cyber operations.

If there are any norms at all, it’s that anything goes. As former President Barack Obama suggested in 2015, it’s the “wild, wild West” when it comes to cyber. There is no international cyber treaty. But perhaps there should be.

On Lawfareblog.com on July 17, Jack Goldsmith made the case that the U.S. would have to check its own actions if there ever were any international cyber norms: “As I have long argued, I think the United States’ failure to look in the mirror is a large part of the problem. This is a difficult and painful thing to say the same day the president of the United States stood next to Putin, discredited U.S. intelligence agencies, and said ‘we’re all to blame’ for the poor state of U.S.-Russia relations. I am certainly not blaming U.S. intelligence agencies, which don’t control U.S. strategic decisions, for anything. But the reality is that the United States government engages in substantially similar behavior to that which the Russians used to cause us great harm [in 2016].”

In other words, President Trump had a point when he suggested that both sides had acted to bring about the current state of affairs. Goldsmith did not do so to suggest there is moral equivalency between how the U.S. and Russia act in the cyber sphere, but simply to observe the reality of the world we are living in, not as we wish the world would be.

Goldsmith also underscores a larger point. If there were international cyber norms via a treaty, the U.S. would be obliged to follow it, too. That would mean no more operations overseas to interfere in elections or engage in hacking.

Is that what Democrats like Ruppersberger really want? Really? It could be pie in the sky, but let’s play along.

If so, then Democrats’ current insistence that the Russia hack be tried publicly in the U.S. makes a certain bit of sense. Then, they are seeking to establish international cyber norms and want to reciprocally foreswear U.S. foreign operations in intervene in the politics of other states in exchange for other countries doing the same. A mutual political non-interference treaty perhaps with the inclusion of no hacking provisions.

On the other hand, if what Democrats really mean is that we expect the rest of the world to stop interfering in our elections and politics, while the U.S. would offer nothing in return to stop our own meddling, such an approach would seem likely to fail, since there would be no incentive to cooperate. Nor would such an approach appear to provide for deterrence against future cyber-attacks. It’s not like nuclear, where deterrence is achieved via mutually assured destruction and humanity’s potential extinction.

So, what to do?

The U.S. should obviously be hardening its cyber defenses. This can be done in the context of building up the infrastructure for 5G and fiber, something Congress may be spending money on anyway. It could include other measures such as hardening the electric grid against a potential electromagnetic pulse.

There is always sanctions, something that was already in effect in 2016 when the DNC and Podesta were hacked. These are retaliatory in nature. They might not have much deterrence value, but these should still be anticipated.

And there is the possibility that some of these disputes might be dealt with internationally via treaties and other agreements. Perhaps there could be some sort of an accord.

On this count, Goldsmith advises, “the United States needs to draw a strong principled line and defend it. That defense would acknowledge that the United States has interfered in elections itself, renounce those actions and pledge not to do them again; acknowledge that it continues to engage in forms of computer network exploitations for various purposes that it deems legitimate; and state precisely the norm that the United States pledges to stand by and that the Russians violated. It is revealing that the United States has done none of these things. And it is unclear whether it can do them. But this is a necessary first step to creating norms to prohibit what happened in 2016.”

That is a tall order, mostly politically. This was something Obama supported in 2015, when he suggested, “We have to make cyberspace safer. We have to improve cooperation across the board. And, by the way, this is not just here in America, but internationally…”

Could President Trump propose a cyber treaty to bring order to the current chaos in the cyber sphere, specifically outlining the dos and don’ts? Democrats should be careful what they wish for. Trump might actually try.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.