In 1963, Karl Popper proposed that the central criterion of the scientific method should be its testability, or the ability to falsify a theory. Absent that, he wrote that such a theory could not be considered scientific.

Popper wrote, “A theory which is not refutable by any conceivable event is non-scientific,” adding, “Irrefutability is not a virtue of a theory (as people often think) but a vice.”

Although controversial, in science, the whole premise of peer review is encapsulated by Popper’s central theme, which is that science as a practice should be transparent. The evidence backing up a scientific theory should be reproducible. Popper wrote, “Every genuine test of a theory is an attempt to falsify it, or to refute it. Testability is falsifiability; but there are degrees of testability: some theories are more testable, more exposed to refutation, than others; they take, as it were, greater risks.”

But many scientific theories, although subjected to peer review, are often not subjected to public review, particularly when it comes to government agencies that rely on published science to enact regulations. While some agencies do require publication of underlying data to support regulations — the National Institutes for Health stands out — there is by no means a legal requirement that they do so, either for issuing regulations or receiving government grants.

That could change, however, with legislation by outgoing U.S. Rep. Lamar Smith (R-Texas), H.R. 1430, the Honest and Open New EPA Science Treatment Act of 2017 (HONEST) Act that would, according to the bill’s description, “prohibit the Environmental Protection Agency from proposing, finalizing, or disseminating a covered action unless all scientific and technical information relied on to support such action is the best available science, specifically identified, and publicly available in a manner sufficient for independent analysis and substantial reproduction of research results…”

The bill passed the House in March 2017 but so far almost no action has been taken in the Senate, and with the incoming Democratic House majority that most certainly will not pass it again, the current Senate lame duck session could be the last chance for Smith’s bill to be enacted.

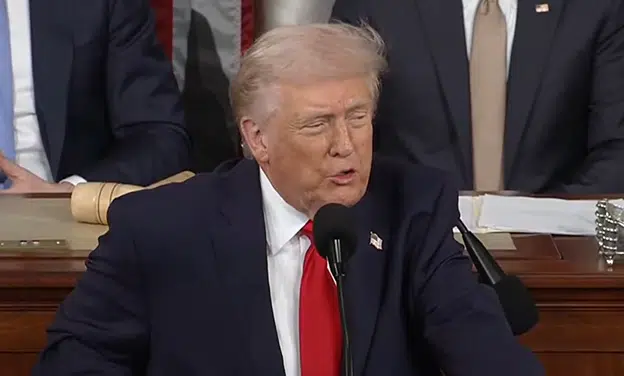

But the Trump administration is not sitting around waiting for Congress to act. In April, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed a new rule, “Strengthening Transparency in Regulatory Science,” which would simply require that “for the science pivotal to its significant regulatory actions, EPA will ensure that the data and models underlying the science is publicly available in a manner sufficient for validation and analysis.”

After all, federal agencies are already required to put together programs for scientific research, grants and the use of that research in rulemakings. Under 42 U.S.C. Section 7403(b)(1), for example, the EPA Administrator is already required to “collect and make available, through publications and other appropriate means, the results of and other information, including appropriate recommendations by him in connection therewith, pertaining to such research and other activities.”

A reasonable interpretation of the statute is that the EPA Administrator can “make available, through publications” the “data and models underlying the science” used in rulemakings.

Other agencies beyond the EPA have similar authority to conduct research and publicize it. Which is why President Trump should expand the EPA rulemaking to include all government agencies via executive order — to ensure that all data used by the federal government will be subjected to public scrutiny.

Yet, Robert Bazell at The American Prospect finds any call for transparency “despicable” and makes dire predictions that such regulation “will cost lives.”

Bazell also makes the absurd contention that the Smith legislation or the EPA regulation would somehow prevent government agencies from issuing regulations based on data that included private medical information. That’s a talking point, or at worst, a legal dodge, not a serious objection. Agencies like the National Institutes for Health already publish their data, including medical data, which is anonymized, in accordance with the HIPAA Privacy Rule.

Of course, and obviously, any publication of scientific data for research purposes must comport with HIPAA requirements. HIPAA does not prevent research from occurring. To the contrary, it provides a clear exception for it, limited in scope to preserve patient privacy while still allowing necessary scientific inquiries to be made by public health and other authorities. As long as agencies continue to follow those rules, there should not be a problem with more disclosure.

Making scientific data publicly available will fuel scientific research and innovation. Standing up artificial roadblocks, like pretending that medical data cannot be anonymized to make it suitable for publication when it already is silly. Anonymizing medical data used in issuing regulations is an easy workaround and already standard practice.

As Popper would have noted, failing to subject science to testing and potential falsification is inherently unscientific.

No serious scientist fears scrutiny of his or her theories as testing and falsification are already embraced as a part of the process. Science must not be performed only behind closed doors beyond public scrutiny, especially when the laws and regulations we live by are made using that science. It’s not too much to ask.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.