Last month, China reported growth of its economy in 2018 at 6.6 percent, the lowest in 28 years. The slowdown is real enough but whether it results in a grand trade deal by the U.S. and China may depend on how much pain China is really feeling at the moment.

Is Beijing feeling the pinch?

Currently, the U.S. is levying 10 percent tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods shipped to the U.S. that came atop a 25 percent tariff on $50 billion of goods from China.

While the talks were ongoing, Trump gave China a 90-day reprieve from the 10 percent tariff also rising to 25 percent, which was supposed to happen at the beginning of the year.

That’s the U.S. leverage. If the U.S. and China do not reach an agreement, then the tariff will more than double.

On the other hand, 2017 set a record for the trade deficit in goods with China at $377 billion according to the Census Bureau.

2018 will be even worse. Excluding November and December data not yet available for 2018, the goods trade deficit from Jan. 2017 to Oct. 2017 was $309.3 billion. For Jan. 2018 to Oct. 2018, it is up to $344.5 billion, an 11 percent increase.

By the time the rest of the 2018 data comes in, the trade in goods deficit with China could exceed $410 billion. And that’s with the already enacted tariffs in place.

This raises a big question of whether the proposed tariffs are big enough to eliminate China’s cost advantage and shift production back to the U.S. So far, the initial tariffs have not made a dent in the trade deficit. Not even a scratch.

China’s real manufacturing advantage comes on account of a combination of lower labor costs, fewer regulations and access to rare earth metals used in high-tech computer components.

We’re not really mining rare earths that much. We still import about 78 percent of our rare earths from China. And it’s one area where Trump has been reluctant to enact tariffs against.

China and other east Asian countries continue to dominate the textile manufacturing sphere in exports to the U.S., according to data compiled by the World Bank, with the U.S. importing more than $40 billion worth in 2017 from China.

The advantage on consumer goods remains similar, with the U.S. importing more than $226.6 billion worth from China in 2017.

While U.S. manufacturers are continuing to experience a resurgence — adding 454,000 jobs since Trump took office in Jan. 2017 — still, the U.S. has a long way to go to reclaim its prior dominance in this sphere. While data for 2018 are not yet fully available, the preliminary results from Census on the trade deficit suggest China continues to expand its market share of exports to the U.S.

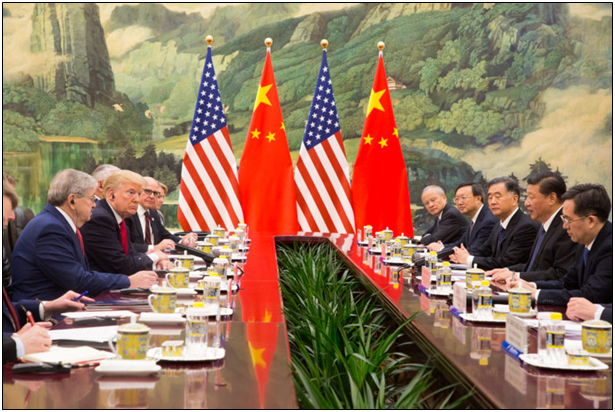

As trade negotiators from both countries continue to meet, a final deal will have to be ironed out by President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping, according to Trump who tweeted on Jan. 31: “No final deal will be made until my friend President Xi, and I, meet in the near future to discuss and agree on some of the long standing and more difficult points.”

Currently, U.S. trade negotiations of China revolve around access to markets, currency valuation and intellectual property theft.

Trump articulated some of these sticking points on Jan. 31, stating, “Looking for China to open their Markets not only to Financial Services, which they are now doing, but also to our Manufacturing, Farmers and other U.S. businesses and industries. Without this a deal would be unacceptable!”

Some good news came as China agreed to import some more soybeans from the U.S., which it has been levying tariffs on. But soybeans is hardly the whole ball game. Those tariffs were retaliatory against the U.S. China lifting those tariffs in part and allowing some soybeans in merely gets you back to where you started.

But the real question might be if China has enough of an incentive to move forward with a deal. On paper, cases can be made that each side has strengths it brings to the table.

And if a deal was made, how much would it result in manufacturing shifting back to the U.S.?

Now, that doesn’t mean that there isn’t a deal to be made. Analysts for years have speculated that China’s growth rates reported are overstated. If true, then the 6.6 percent rate being reported could indicate that real pain is being felt, and that Trump’s threatened 25 percent tariff rate would make that even worse. The question is whether the U.S. will get enough in return for not enacting it.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.