One of the centerpieces of the Trump administration’s deregulation agenda is the rescission of the Clean Power Plan that was put into place by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2015 under former President Barack Obama. Comprising in part the new and existing power plant rules by the EPA, the Obama plan was to reduce carbon emissions by retrofitting existing coal power plants and making the costs of building new ones so onerous that nobody would dream of it.

By and large, the Obama policy was a “success,” if by success we mean that existing coal plants were taken off-line and replaced with natural gas, and the new plants being built run on natural gas.

In 2007, coal-generated electricity made up 49 percent of the total U.S. grid, while natural gas was just 21 percent, according to the Energy Information Administration.

In 2018, after Obama, now natural gas makes up 35 percent of the grid, and coal is down to 27 percent.

What made this overreach possibility — a de facto ban on new coal power plants and a major incentive to convert existing ones to natural gas — was the 2009 carbon endangerment finding by the EPA, defining carbon dioxide as a harmful pollutant under the terms of the Clean Air Act.

To address this war on coal, the EPA has now come back with a plan to modify the standards under the new power plant rule, while still imposing emissions reductions, doing so in a manner that is actually technically feasible and achievable. Instead of limiting new larger power plants to 1,400 pounds of carbon dioxide per megawatt hour, which the agency said was too onerous to be met, it will make it 1,900 pounds.

As for existing plants, the EPA proposes for states to decide for themselves how to reduce carbon emissions. If states fail to produce a plan, then the EPA will give them one.

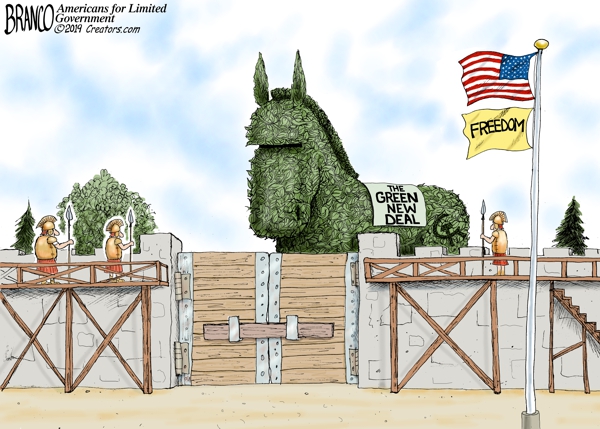

Both of these proposals would certainly be a step in the right direction and afford more latitude to meet emission reduction targets but they still accept the central premise that carbon dioxide is a harmful pollutant and must be addressed under the Clean Air Act. They leave the carbon endangerment finding in place, creating an opening for future administrations to come back and just do the same thing again — or worse, implement something like the Green New Deal, which ambitiously contemplates getting to net zero carbon emissions within 10 years.

This minimal progress being made is not unexpected. It is a lot harder to rescind regulations and have courts sustain that rescission than it is to water them down a bit via a modification. In 1983, the Supreme Court unanimously decided in Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Association v. State Farm Mutual that in rescinding a regulation, the agency must provide a reasoned analysis, “for the change beyond that which may be required when an agency does not act in the first instance.”

This leaves every rescission subject to judicial review, where you have to prove not only that rescinding the regulation in question is rational based on the statutory scheme, but prove that enacting it was irrational to begin with. The problem in this case is that the Supreme Court already decided in Massachusetts v. EPA in 2007 that carbon dioxide could be regulated under the terms of the Clean Air Act even though the law never contemplated doing so.

In other words, it was “reasonable” based on the 2007 Supreme Court ruling to implement the carbon endangerment finding and so too were the Obama rules that sought to reduce carbon emissions within the statutory scheme. If the Trump administration simply rescinded the regulations, it would likely face an uphill battle in court, since ultimately the question would boil down to persuading the Supreme Court to second-guess itself in the 2007 ruling or not.

If the courts were to block an attempt to rescind the regulations, it could be argued the Trump administration had squandered an opportunity to clarify them instead into something that would at least allow for new coal plants to be built and save a dying industry.

On the other hand, it is a good question whether it would be worth the risk of losing to rescind the regulations in this case. Justice Anthony Kennedy was the swing vote in the majority opinion in the 2007 case, a 5 to 4 decision, and is no longer on the Supreme Court. This might be the best, last opportunity to revisit the carbon endangerment finding.

Other avenues of potential remedy appear to be cut off at the moment. Congress could have addressed this issue in 2017 and 2018 when Republicans controlled majorities in both chambers of Congress, and clarified the terms of the Clean Air Act either by reforming the statute or by defunding implementation of the Obama era regulations but that was not even attempted — it would have likely stalled in the Senate failing to get to 60 votes and the GOP Senate had already foreclosed the possibility of eliminating the filibuster — and so President Trump is left with what he can do under limited discretion the agencies have to modify the existing regulations.

Unfortunately, what that means is that to prevent something like the Green New Deal from being implemented via regulation, Republicans will have to win every election from now on. In the least, the GOP would need to win back the House in 2020 and hold the Senate and White House. To prevent the Green New Deal, the Clean Air Act needs to be reformed to rule out carbon emissions regulations or else the Supreme Court needs to go back on its 2007 decision.

What it really comes down to is even with these new regulations, will investors want to risk building a new coal power plant, knowing that it’s just one election away from being shut down again? The coal industry may need more permanent protections via law. The regulations keep changing.

Also, the President’s Commission on Climate Security is an important step to addressing whether such onerous regulations are even necessary, as it will take a second-look at the science behind man-made climate change. But it is Congress that really needs to act.

Arguably, under the existing statutory and regulatory scheme and judicial precedent, Democrats already have everything they need to one day implement the Green New Deal via regulation, effectively banning carbon emissions by making carbon capture requirements so onerous nobody can comply with them. Do we really want to sit around and wait and see if they are successful in jamming it through the regulatory process and the courts — and consigning the U.S. to economic oblivion?

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.