Just when it appeared that a new trade agreement with China was being finalized last week, Beijing abruptly attempted to change all the terms of the deal and walk back prior concessions that had been made to head off President Donald Trump’s threat to increase tariffs from 10 percent to 25 percent on $200 billion of goods.

The changes had arrived on May 3 late in the evening and blew up months’ worth of negotiations.

According to Reuters’ David Lawder, Jeff Mason and Michael Martina, “In each of the seven chapters of the draft trade deal, China had deleted its commitments to change laws to resolve core complaints that caused the United States to launch a trade war: Theft of U.S. intellectual property and trade secrets; forced technology transfers; competition policy; access to financial services; and currency manipulation.”

It was an unacceptable situation. China was reneging on the deal. Trump had already delayed the 25 percent tariffs in January to give negotiations a chance to make a breakthrough. Then, on the eve of concluding the agreement, Beijing wanted to do a complete 180 on everything that had already been discussed.

Instantaneously, and in response, on May 5, President Trump said that the new tariffs were going into effect, giving May 10 as a hard deadline, which has now passed. The tariffs went up at midnight.

China’s erratic behavior in the past week necessitated Trump’s tariff threat, if for no other reason than to get the negotiations back on track. It could be argued that the only reason for the negotiations in the first place was because of the imminent tariffs.

Now, we can only surmise the apparent concessions by China were merely a delaying tactic, intended to test out how committed Trump was to the tariffs. And now China knows President Trump means business.

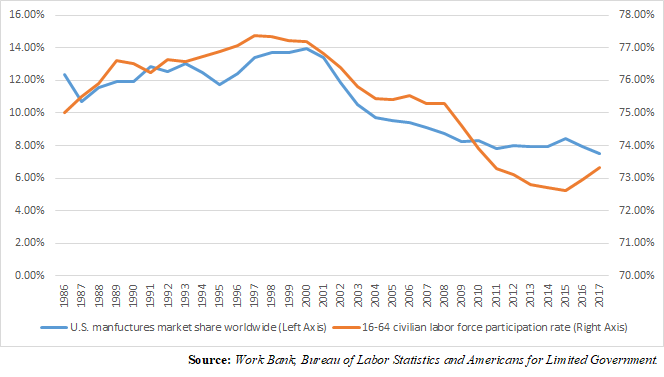

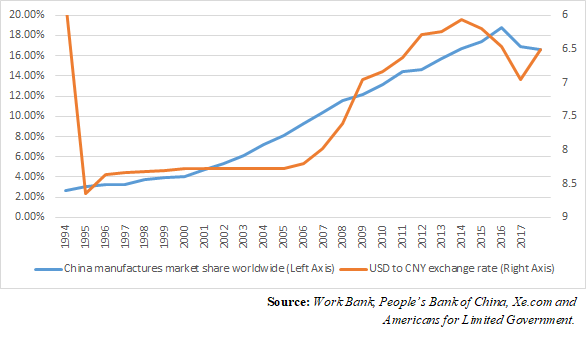

Which, it’s time to get tough. Since China entered the World Trade Organization in 2001, U.S. manufacturing market share has dropped from 13.4 percent to 7.5 percent in 2017, according to World Bank data. China has risen from 5.3 percent to 16.6 percent in 2017, although their percent of global manufacturing market share has peaked in 2015 at 18.8 percent.

During that time, the U.S. economy has not grown above 4 percent since 2000, and not above 3 percent since 2005 on an annual basis.

The trade in goods deficit with China hit a record high in 2018 at $419.1 billion according to the U.S. Census Bureau. And that was with President Trump’s 10 percent tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods that came atop a 25 percent tariff on $50 billion of hi-tech goods.

Fueling the shift in production has been a competitive devaluation of China’s currency, the yuan. From 2014 alone, after a period of revaluation that could be accomplished as its global market share was still increasing, Beijing shifted from being worth 6.05 per dollar to about 6.8 per dollar today, a 12.6 percent devaluation.

China has a lot more to lose in a trade war than the U.S., too, according to data by the U.S. Trade Representative. China’s $539.5 billion of goods exports to the U.S. comprised almost 4.1 percent of its $13.28 trillion Gross Domestic Product in 2018 and about 22.5 percent of its $2.4 trillion of goods exports. In contrast, American goods exports to China were $120.3 billion, comprising 0.58 percent of the 2018 annual GDP of $20.5 trillion, and comparatively 7.2 percent of its $1.66 trillion of goods exports.

From 2000 to 2016, the U.S. lost nearly 5 million manufacturing jobs. There was some recovery after the financial crisis, and in addition, 470,000 manufacturing jobs have been created since President Trump came into office in 2017.

Labor participation among working age adults has dropped significantly through 2016, accounting for about 9 million people who would have been participating in the economy had labor participation remained the same. Since President Trump took office, that number is down to about 6.9 million or so as working age labor participation has increased, thanks in part to Trump’s new trade policies but also tax cuts and deregulation to make the U.S. more competitive globally.

None of the bad things that were supposed to happen because of the tariffs have come to pass. The economy grew at 2.9 percent in 2018. It has accelerated to 3.2 percent in the first quarter.

Unemployment is at a 49-year low at 3.6 in April.

Inflation is normal at about 2.0 percent the past 12 months.

The negotiations are still ongoing, and a deal may still be had, but even if that does not happen, the world is not ending. The sun still rose today.

The point is, there is most certainly a case to be made for the President’s tariff stance. If anything, the question about the new tariff is not whether it is justified, but whether it is big enough?

Correction: The Bureau of Labor Statistics updated the consumer price index this morning, bringing inflation for the past 12 months at 2 percent. Also, if labor participation had remained what it was in 2000, there would be 6.9 million more people in the labor force today.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.