The Wall Street Journal is reporting that momentum is building for the U.S. government to subject Google and other Big Tech firms to antitrust scrutiny for fears that they have become too big and too powerful.

In today’s digital ecosystem, politicians, political parties, organizations and media all rely on social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Google and Youtube to get the message out because that’s where consumers by and large go to in order to consume information.

A Pew report found 68 percent of adult Americans use Facebook, or over 170 million. 24 percent use Twitter, or about 61 million. A separate Pew report found 73 percent, or 185 million, use broadband internet. Statista reports that Google’s family of sites are the most popular in America, with 255 million unique U.S. visitors in March 2019 alone.

So, the internet is indisputably a huge part of the way people are getting information nowadays.

Now, conservatives and Republicans have become alarmed as many of these platforms are censoring and restricting speech that does not coincide with Big Tech’s social justice agenda. Deplatforming is real. Actor James Woods has been censored on Twitter, Stephen Crowder has been demonetized on Youtube (owned by Google) and Candace Owens was temporarily suspended on Facebook before the company did a reversal and declared it “an error.”

Political discrimination is destructive as it creates an incentive to silence your political opponents. Suddenly you have countrymen reporting on one another to get them deplatformed. Is this healthy for a society?

But it is not merely the reporting features that are being abused on these platforms.

Project Veritas’ James O’Keefe released a video on June 24 that showed how the algorithms that produce Google search results (and other machine learning) are programmed with algorithmic “fairness” in mind to prevent, per an internal 2017 Google document, “unjust or prejudicial treatment of people that is related to sensitive characteristics such as race, income, sexual orientation or gender, through algorithmic systems or algorithmically aided decision-making.”

Just throw in political affiliation, philosophy or religion, and one can immediately recognize how Republicans, conservatives or Christians might feel marginalized on social media platforms, but Google did not end up looking into that. A study by Google in 2018 on algorithmic fairness stated, “due to our focus on traditionally marginalized populations, we did not gather data about how more privileged populations think about or experience algorithmic fairness.”

As a Google executive in the video who was quoted in an undercover camera noted, “Communities who are in power and have traditionally been in power are not who I’m solving fairness for.”

But if Google had looked at other groups, they would have likely found found that supposedly “privileged” populations can feel marginalized, too. The 2018 study unsurprisingly found that participants expressed, “In addition to their concerns about potential harms to themselves and society, participants also indicated that algorithmic fairness (or lack thereof) could substantially affect their trust in a company or product” and that “when participants perceived companies were protecting them from unfairness or discrimination, it greatly enhanced user trust and strengthened their relationships with those companies.”

The thing is, nobody wants to be discriminated against, and if they are it will affect their perception of the company or companies that are doing it. Deplatforming, censorship and manipulating search and news results undermines trust in these Big Tech firms, and suddenly makes them a problem that many want to solve. No need for another focus group.

So, what responsibility does Big Tech have to foster our way of life and our competitive system of representative government, if any?

I would argue just as much responsibility as they feel to tackle the issue of fairness for historically marginalized groups, if for no other reason than it is good, sound business to cater to all comers, particularly in the political and governmental sphere. Why make enemies? It’s provocative.

Many solutions have been proposed to help there to be a level playing field on the Internet. Some are heavy-handed and appear to miss the target, while others are more narrow.

There is the Federal Communications Commission route, which might seek to make public utilities out of Big Tech companies, and all the regulation that comes with that. Net neutrality springs to mind, although that appeared more focused on throttling broadband speeds due to how much data was being used, whereas the issues today appear to focus on content-based censorship.

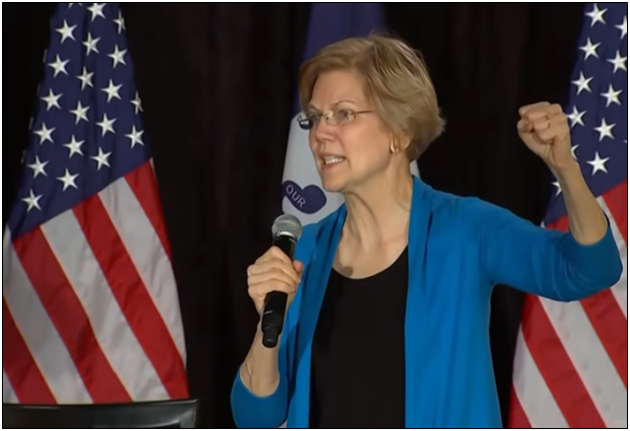

There is antitrust approach, whether via the Federal Trade Commission or the Department of Justice Antitrust Division, that might envision breaking up these large companies. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) has come out for this approach. In a recent statement, she said, “As these companies have grown larger and more powerful, they have used their resources and control over the way we use the internet to squash small businesses and innovation, and substitute their own financial interests for the broader interests of the American people. To restore the balance of power in our democracy, to promote competition, and to ensure that the next generation of technology innovation is as vibrant as the last, it’s time to break up our biggest tech companies.”

Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act exempts “interactive computer services” from liability of what their users post, and grants them the power to remove items at their discretion they find objectionable. Some have proposed simply removing the liability protections, which would render sites that allow users to write whatever they want suddenly subject to liability of hundreds of millions of users. It would also effectively destroy the Internet, since nobody would be willing to assume the risk of hosting somebody else’s material that might be defamatory.

Some have called for conservatives to boycott these platforms and to take their business elsewhere or to make their own platofrms, but what sort of echo chamber would we wind up with? More to the point, to win elections, Republicans have to appeal to independents and unaffiliated voters. You buy ads where there’s ad space to reach undecideds. Insular practices of exclusively only talking to partisans on your side is a recipe for being in the minority for a very long time. It does not grow a political movement to do that.

This author has posited that perhaps Congress could narrowly expand the franchise of protected groups under civil rights to include politics, philosophy and the like (although excluding employment hiring for exclusive organizations like political parties and organizations) and defining interactive computer services as public accommodations so that services cannot be denied on the basis of partisan differences. Throw in banking, DNS resolution, web hosting and email services as public accommodations while we’re at it for good measure.

From the perspectives of the Big Tech companies, surely they have noticed a marked uptick in calls to regulate their firms? Conservatives complain about censorship. Elizabeth Warren is worried about smaller businesses. The calls for regulation are directly proportionate to how powerful these firms have become. Do any of the above options sound profitable or more like a regulatory headache that will cost millions or billions of dollars to manage?

And these are not even things we would normally consider, but throw in the prospect of censorship and suddenly it’s an existential matter of survival. Republicans who might normally defend these companies from regulation might look the other way when it comes up now. See how that works?

The truth is, I’m taking time out of my column to focus on this issue and so are many other organizations that are worried they too could be censored. The platforms we’re talking about have such market saturation that is so pervasive it could be utilized to discriminate on the basis of politics in order foster conditions conducive to one-party rule, which I believe to be dangerous.

More broadly, groups like Americans for Limited Government and political parties depend on a competitive political system to function. If we and others like us were suddenly barred from posting on social media or hosting a website or sending emails, suffice to say we would not function for much longer.

In a representative form of government, political parties’ access to media and their followers are critical to building and growing constituencies, and in the digital age these represent a digital sort of civil rights, and they must be protected in order for that system to continue to exist. One party systems do not respect civil rights. They squelch dissent to consolidate power and they target political opponents and critics of the system.

The great Renaissance philosopher Niccolo Machiavelli supposed that there were but two forms of government, republics and principalities, perhaps for that reason. One is ruled by the consent of the governed and the separation of powers, and the other by the will and domination of the state and over time needs to instill fear in order to govern.

There are liberal democracies that foster debate, and then there are one party systems that demand loyalty to the state. There’s not much in between.

The alarming trends we’re seeing with Big Tech companies engaging in censorship in the pursuit of “fairness” look a lot like a bid for one party rule. And the thing about one party systems is, once you have one, it’s really, really hard to get rid of it and there’s no guarantee that your favored class will be represented in its leadership. Sometimes those who support the rise of such a system wind up being marginalized by it. Look no further than Elizabeth Warren to see what lies at the end of that tunnel. Is it worth the risk? Be careful what you wish for.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.