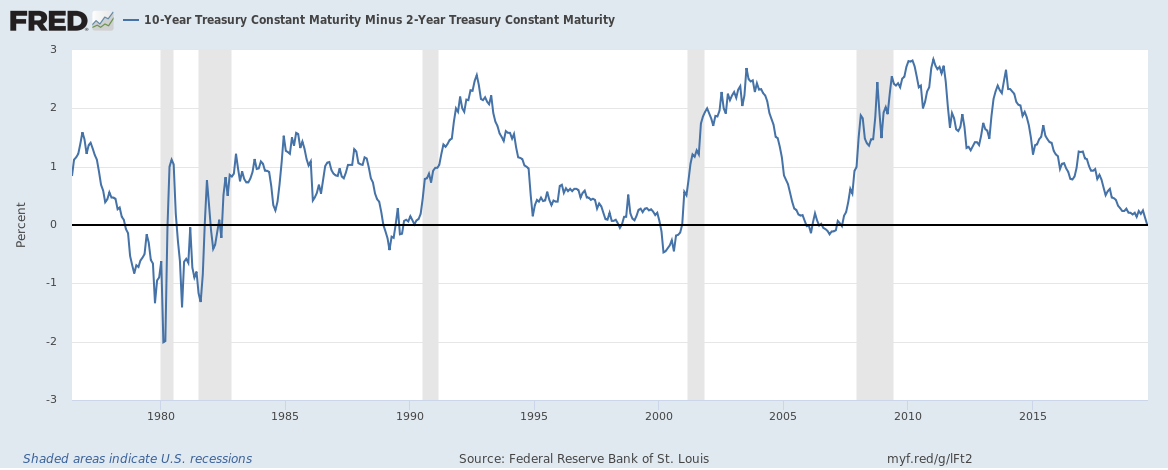

The 10-year, 2-year treasuries spread was bound to invert eventually.

It’s been a full 12 years since the last inversion, after all, and a full 10 years since the last recession. Is anyone really surprised? The economy is not a perpetual motion machine.

Still, that didn’t stop equities markets from suddenly dumping shares on the news that the 10-year, 2-year treasuries spread — the difference between the interest rates of the 10-year and 2-year treasuries that usually precedes the next recession — briefly dropped below zero, although remained positive for the rest of the day.

How long until it fully inverts is a question as it went negative overnight again but is slightly positive as of this writing, and yet looking at the long-term chart, it won’t take much for it to go negative and then stay there for some time. We’re simply getting near the end of the business cycle.

The fact is, we’ve been sitting on the precipice for many years now. The U.S. economy is long overdue for another recession. It averages one every 5.3 years since World War II, according to data compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Research. After 10 years without one, we’ve been living on borrowed time.

Now, how steep the recession, when it does happen — which on average is about 16 months after this key inversion, which would put a potential recession somewhere around the end of 2020 — is another matter entirely. Maybe a better question is, what should we be doing to prepare for it?

Of course, good luck getting politicians to discuss it rationally with political season upon us. Seeing a potential recession signal, Democrats will automatically want to pin blame on the incumbent Trump.

Republicans will urge caution and point to strong economic indicators such as the near-50-year-low unemployment rate at 3.7 percent, and that’s all well and good. After all, sometimes you get false signals.

In Jan. 2016, I would have sworn to you that we were on the cusp of another downturn (in fact, I did). Stocks were taking a hit, China was crashing, oil was down to $29 a barrel and 10-year treasuries had crashed below 2 percent in a flight to safety. By July 2016, the 10-year, 2-year spread was all the way down to 0.76 as the 10-year treasury hit 1.36 percent, the lowest it had been in decades.

In my Jan. 2016 piece, I wrote, “Heck, it’s been eight years since the last recession. Why not another one now? In that sense, you almost feel bad for the next president, considering the cyclical nature of these things. The U.S. averages a recession once every 6 to 7 years, and we’re due.”

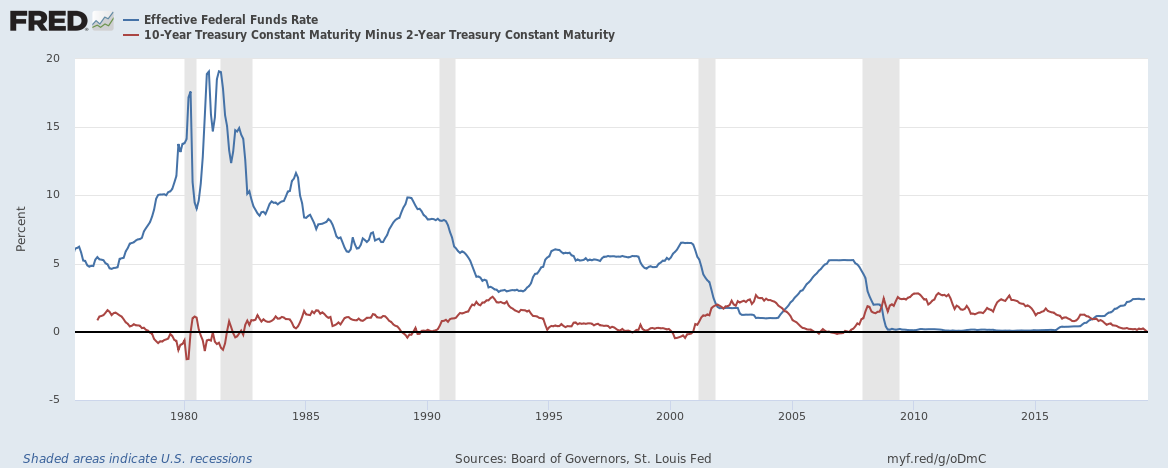

Of course, as I noted then, it’s a crapshoot trying to predict the next downturn. Turns out the timing was wrong. At that point, the Federal Reserve had only just begun normalizing the federal funds rate from its near-zero percent levels left over from the financial crisis beginning in Dec. 2015. And just with their quarter percent uptick, markets panicked. When the Fed forestalled any more rate hikes until after the election, and after Trump won, the 10-year treasury did a swift turnaround, the stock market boomed, oil prices had recovered along with Chinese stocks, and the inversion was averted that year.

Was that politically timed until after the election? It looks that way. And in terms of timing the next recession, 2020 is a real possibility now. We can argue about what might have happened had the Fed normalized in, say, 2015 when the economy grew at 2.9 percent. We might have already experienced the next recession for all we know. I certainly thought at the time that the federal funds rate was long overdue for normalization and that the Fed had waited too long. In fact, it waited until after the election to fully hike the rates.

But it’s impossible to know the counterfactual. All we can do is see where we are now.

And right now, Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan is already talking up the possibility of negative interest rates. With such little wiggle room, and interest rates already quite low — rates tend to drop in recessions in a flight to safety — it seems likely the Fed could follow Japan’s lead and utilize negative interest rates in the next downturn. What will that mean for our economic system and the future of economic growth?

Interest rates are an indicator of future expected growth. If somebody as smart as Greenspan thinks they’re going negative, watch out. Not only will it hurt growth, it raises questions about incentives to lend and borrow.

Elsewhere, President Donald Trump has delayed some implementation of his additional 10 percent tariff on $300 billion of goods until Dec. 15, a three-month delay, giving China more time to consider what it wants to do on a trade agreement.

On Twitter on Aug. 14, Trump wrote, “Good things were stated on the call with China the other day. They are eating the Tariffs with the devaluation of their currency and ‘pouring’ money into their system. The American consumer is fine with or without the September date, but much good will come from the short… deferral to December. It actually helps China more than us, but will be reciprocated. Millions of jobs are being lost in China to other non-Tariffed countries. Thousands of companies are leaving. Of course China wants to make a deal. Let them work humanely with Hong Kong first!”

Also, Beijing has certainly devalued the yuan in response to the tariff threat from Trump as China experienced its slowest growth in almost three decades. And the dollar could be a little too strong relative to other currencies, something the President has been concerned about.

I’m concerned about that, too. Having a strong currency is a choice. It didn’t help during the Great Depression when the federal government stuck to the interwar gold standard while the rest of the world was abandoning it as unemployment spiked. My thinking is nobody’s talking about negative interest rates as a solution if the dollar isn’t so strong. Trump is wise to continue talks with China, because we need to resolve this issue before events shift beyond either Beijing or Washington, D.C.’s control and only bad choices are presented to us.

All these factors could very well weigh on the economy. But there’s no need to panic. Every recession is different, and the next one may not even hit until after the 2020 election is all over with. We’ll see. We’ve been here before, and I suspect we’ll survive it. But with talk of negative interest rates or policies like universal basic income in the wake of the next downturn, what we need to make certain of is that liberty, limited government and capitalism survive, as well.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.