Another 5.2 million Americans filed for initial unemployment claims last week, bringing the total number of jobs lost to the Chinese coronavirus and related government closures to anywhere from 21.8 million to 24.8 million jobs lost in about one month, and when added to the 5.8 million who were already jobless, produces an effective unemployment rate of 16.7 to 18.5 percent.

That’s already almost triple the number of jobs lost in the 2007-2008 financial crisis and ensuing recession, when 8.3 million Americans had lost their jobs by Dec.2009 and more than 6 million foreclosures occurred between 2007 and 2010. Joblessness has not been this high since the Great Depression.

If the same proportion of homes lost to jobs lost holds true today in the event we have a long-term unemployment problem, as many as 15 million to 18 million households could be in jeopardy of falling behind on their mortgage payments right now — through no fault of their own. They had great jobs and were making good money to live in a nice home, and now it could all be washed away by the recession onslaught brought on by the virus.

Many banks are already providing temporary forebearance and deferral options for mortgage payments that must be paid back for any delinquency on a separate payment plan, or outright deferral with the delinquent amounts being added to the mortgage principal.

In addition, there is also a moratorium on foreclosures and evictions by the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve, but those who have already lost their jobs are in danger of falling behind on their payments and losing equity in their homes right now. Fortunately the job losses only began a month ago, but already the effects may already be trickling into the financial system that could become a torrent should it go on too long.

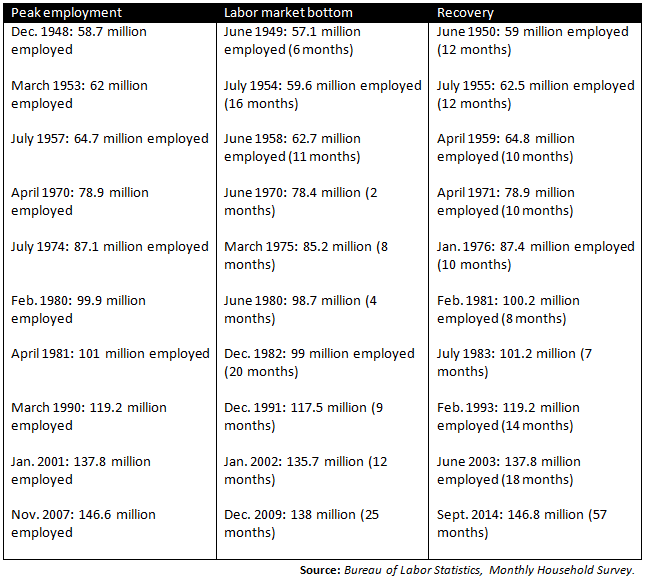

The trouble is the amount of time it takes for a recession to run its course, with job losses to recovering those jobs lasting on average 27 months since 1948 — 11 months to lose all the jobs, and 16 months to get them all back. But if you look at the financial crisis and Great Recession, which may be a more relevant example, it took 25 months to lose all the jobs, and 57 months to get them all back. Of note, the past three recessions have progressively taken longer to recover from, at 14 months to 18 months and then 57 months in the last one.

So, banks might be able to defer or reduce payments for a few months, but in the end, if unemployment turns out to be a much longer term problem, then so too will foreclosures eventually become a problem, the current moratorium notwithstanding. The danger comes if the recession lasts longer than anticipated and suddenly homeowners are either way behind on their payments or they lost a ton of equity when the moratorium ends and find themselves upside down if, say, property values plummet during this recession.

For middle and upper middle class households, the expanded unemployment proceeds plus the checks going out, particularly in more expensive states, may still not be enough for millions of households who are already experiencing unemployment. Households whose revolving debt loads were already high will be impacted greatly. The wealthiest could actually be hit the hardest in these circumstances, as unbelievable as that might sound to the lay person, because they will have to simultaneously assume considerable capital losses on equities to get to cash, which are still in practical bear market territory.

Into the mix, we must also consider the very strong possibility that governors of larger states with bigger metropolitan areas, Democrats and Republicans alike, are going to take considerably longer to reopen than smaller states, cities and towns that have flatter curves in terms of the rate of infection by the virus. Longer periods to reopen, then, will undoubtedly mean millions of more unemployed and longer periods of unemployment, too, and therefore even more potential foreclosures than is currently being discussed.

And so we may need a temporary bank holiday to prevent another financial crisis much, much larger than the last one. That is, if we want there to be a middle class when this is over. Not even the wealthy may have enough savings to not work indefinitely because they have larger mortgages, as we learned in 2008. The higher the property values, the bigger the problem. Those of you living in more expensive states who are at risk of losing their jobs or already have know exactly what I’m talking about.

This gives some context to the current anxiety over how and when states might begin reopening. There are very understandable concerns on the public health side, and those on the economic side are equally sobering. But still not knowing when we might reopen definitively for each state is a huge red flag that the potential downstream costs have not been fully contemplated by the federal and state governments.

For example, if in reality we’re actually talking months and not weeks to get past this current period for larger states and metro areas where property values are the highest and unemployment will likely be the worst — and maybe even until we get a vaccine for the virus — we need to know that right now.

State governors must be clear about what it will take for them to reopen, because Congress, Treasury and the Federal Reserve must be prepared now, not later, for those contingencies that have yet to be defined.

Under these circumstances, periodically returning to Congress to address these concerns every few weeks when another critical part of the economy breaks could result in millions more households getting behind on their payments, ultimately culminating in another foreclosure crisis when things finally do reopen that will make 2008 look like a blip on the radar. Again, we’ve already lost triple the jobs compared to the last financial crisis. Expanded unemployment benefits and the checks now going out may not be enough to cover the damage that’s already been done, especially in areas with higher costs of living.

Whatever choice we make right now must be both politically and economically sustainable. That has to be the rule. Does the above scenario sound sustainable to anyone? Governor Cuomo? Anyone?

State and local governments have their own problems, where the essence of the crisis is they are rapidly running out of taxpayers to cover the costs of everything on government ledgers, in addition to so many losing their jobs in the private sector to continue servicing their own privately held debts. This toxic combination could collapse not only the financial system but society itself.

This could be an economic suicide pact if the proper measures are not taken.

The U.S. labor force is currently contracting at a rate about 3 to 4 percent every week! So, for governments, that means state and local revenues are falling at about the same rate. It appears to be more expensive to leave things closed than to have them open, despite utilizing fewer resources, as unbelievable as that sounds.

Another problem is that currently, Congress is attempting to deal with this emergency on the fiscal side where the administration may have to keep going back to Congress when further assistance is needed, and even then what they’re producing out of Congress is actually quite meager despite the gargantuan price tag when balanced against the real need. Consider that, the legislation Congress passed is by far the largest in American history, and might not be enough.

To be sure, the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve should have access to accurate, up-to-the-minute data that will tell them how many households are about to fall behind on their payments and by how much. They need to look at the drop in FICA payments already occurring and then compare the incomes that existed above that but suddenly do not anymore. Similar analysis will probably need to be prepared for municipal bond markets. The shortfalls being experienced or that we’re about to experience must be colossal.

Treasury and the Fed should also consider whether the bill Congress already passed, which can be expanded up to $6 trillion with firepower from the Fed, already would authorize a more aggressive approach and begin making immediate preparations.

If so, then the nation’s top financial officials could move towards a bank holiday rapidly. We might need it right away, not just for households, but for a larger portion of debt service than is currently being anticipated. In truth, only the Federal Reserve has the resources to do this. Anecdotally, my student loan payment has been automatically deferred. Officials should consider whether that might be necessary for a larger share of debt payments across the country.

Here are just a few categories of things the Fed might already be looking at potentially covering. Fiscal conservatives may wish to avert their eyes. But if this really is going to go on for months, not weeks as I am reading from state governors right now who are reticent to even think about when we might reopen, then this contingency must at least be considered. The areas most likely to run into trouble are 1) state and local government revenues; 2) municipal bonds; 2) small businesses; 3) larger employers; 4) mortgages both residential and commercial; 5) credit card bills; 6) student loans; and 7) corporate bonds.

Without widespread deferrals amid mass unemployment already approaching Great Depression levels, even if only, say, 25 percent of individuals and entities fell into this category, that would be more than enough to topple the entire financial system.

Again, the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve has access to all the data they need to determine how many households and, yes, municipalities are about to be unable to service payments. It might be wise to consider debt service assistance for the foreseeable future. That’s what a bank holiday is. In addition to the already approved expanded unemployment plus the checks going out, debt service assistance might be enough to get households through this crisis without any foreclosures and prevent households from falling behind on their payments in the first place.

Such a program can only possibly be undertaken on the monetary side, in my opinion, because not even the U.S. treasuries market are big enough to cover the gaping hole that has been created by the equivalent of a large asteroid striking the global economy.

In 2008, Congress created the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program to address what was more like a $5 trillion problem in mortgage and derivative markets. That is because no matter how big Congress thought the problem was, it was in fact much, much larger than could be politically contemplated. The only way then Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke was able to stop the bleeding was by effectively taking over the delinquent mortgage markets from both the privately issued mortgage-backed securities plus those held by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

To give this scale to the current crisis, Congress passed a $2.2 trillion leverageable up to $6 trillion plan to address what might actually be more like a $20 trillion problem on the backend.

This has to do with the potential cascading effects of tens of millions of Americans suddenly stopping their payments on debt service, which may already be happening or soon will this month and next month en masse. In the financial crisis, that resulted in bond holders who suddenly stopped receiving principal and interest payments, who in turn suddenly stopped making their own debt service payments to major financial institutions, who in turn had nowhere but the Fed to turn to.

It shouldn’t even get that far. The uncertainty in the projection has to do with similar uncertainties about how long the economic shutdown will go on, plus bank exposure in the shadow banking and derivatives markets. It is possible not even the banks know how large the problem is across the system. The only difference appears to be on orders of magnitude. Again, we’ve already lost triple the jobs compared to the last financial crisis. The orderly liquidation fund in Dodd-Frank won’t be enough to cover this on a liquidation basis, nor do I think it should even be considered as an option because it assumes mass defaults.

Now, stemming that tide will be the Fed’s ongoing legacy mortgage-backed securities purchase program from the last crisis, where the central bank takes bad debts off of bank’s balance sheets. But we shouldn’t let it get there, either, because that assumes the foreclosures happen.

This crisis was not the fault of Americans who were working hard and paying all their debts in one of the finest economies in modern history.

In one month, however, again, we have lost almost triple the jobs lost in the Great Recession that took 25 months to be realized beginning in 2007 all the way to the end of 2009. The bill Congress already passed could be adequate to address this since it already provides for the Fed to expand measures as needed up to $6 trillion without any more votes in Congress required to cover whatever needs to be covered. If so, then the action that could still be urgently needed must come from Treasury and the Federal Reserve.

In addition, 38 million Americans in the labor force are 55 years old and older, and 11 million of those are 65 years old and older, such that even if governors say let’s reopen except for older Americans, we’re still talking about almost one-quarter of the labor force who will likely be unable to continue working and servicing their debts. And that’s the so-called Swedish model. It will likely take years to calculate the true costs of the overall closures impacting a far wider swath of the civil labor force than just the elderly, however.

Now, all of the above is completely dependent on what state governors do very specifically on reopening, and what sorts of treatment become available to mitigate the virus’ impact, including any cures that were authorized on an emergency basis by President Trump. Until there is something like that, and we can already anticipate how governors in larger states are going to proceed, it would be irresponsible of Congress, the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Reserve not to contemplate and prepare for the worst case scenario economically that I fear we are already in. The damage may have already been done. We need to get ahead of this storm. The problem is it is already right over our heads.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.

Correction: The number of unemployed total is anywhere from 27 million to 30 million now, producing an effective unemployment rate of anywhere from 16.7 to 18.5 percent.