By Bill Wilson — How is it that a hard Greek default — a tiny country that comprises less than two percent of Europe’s Gross Domestic Product — poses such a systemic risk to the European and, indeed, the global financial system?

By Bill Wilson — How is it that a hard Greek default — a tiny country that comprises less than two percent of Europe’s Gross Domestic Product — poses such a systemic risk to the European and, indeed, the global financial system?

The American Enterprise Institute’s Alex Pollock has the answer, citing a little-understood danger created by the weakening of capital requirements after the financial crisis by the Bank of International Settlements based in Basel, Switzerland. The problem, Pollock writes, is “banks investing in European government debt would for such investments have zero required capital.”

Banks are normally required to hold capital against assets based on their risk. Pollock notes a zero-based capital requirement for sovereign debt “can only make sense if owning this debt has no risk whatsoever.”

Of course, it is not risk-free, so it makes no sense. A Greek default in particular has become increasingly likely in recent days as parliamentary leaders in the Hellenic nation are rejecting demands to cede national fiscal sovereignty to the European Commission, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the European Central Bank (ECB), known as the Troika.

Without an agreement to meet the Troika’s budget targets, Greece cannot receive what remains of its original €110 billion bailout refinance loans, nor an additional €130 billion pledged in October. Just €14.5 billion of debt is coming due on Mar. 20, but a hard default has wider implications.

Of Greece’s €340 billion debt, the ECB holds €55 billion in Greek bonds, plus tens of billions more worth it accepted as collateral when it made other loans. The IMF has lent €23 billion to Greece. The European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) has also lent €53 billion.

The ECB did not pay face value for its purchases, so it stands to lose at the most €41.2 billion on a Greek default for the bonds it holds directly. It might be able to withstand the shock, with €81 billion in capital and reserves on hand, if the other loans are repaid and, importantly, the crisis is contained to Greece.

But if the defaults spread to Ireland, Portugal, Italy, and Spain — of which the central bank holds more than €150 billion — or Greek institutions cannot repay the other loans, the ECB could easily be wiped out. In the least, a hard default by Greece would place severe upward pressure on the interest rates of other countries’ debts.

Then there is the rest of Greece’s debt that is held by private financial institutions, including €80 billion in Greece itself. A hard default would affect these institutions the most, and if the crisis cascades to our Eurozone nations, threatens widespread insolvencies throughout the continent.

But the damage will not be contained there.

U.S. financial institutions are said to be on the hook for as much as $641 billion more in exposure to Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain (PIIGS), according to the Congressional Research Service.

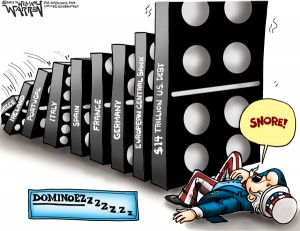

And it all traces back to Basel’s curious declaration after the financial crisis that sovereign debt was risk-free. Financial institutions around the world were already woefully undercapitalized, able to essentially lend money into existence that they never possessed. This broader, fatal flaw to the financial system underpinned the mortgage securities meltdown in 2008, and now, it threatens the entire global economy with sovereign debt dominoes.

The scary part is the U.S. no better off. Like other U.S. financial institutions, the Federal Reserve does not take on additional capital when it lends to the Treasury, viewing its balance sheet. On Jan. 5, 2011 at it had $53 billion of capital and $1 trillion of U.S. Treasuries. Today it still only has $53 billion of capital and but its share of U.S. Treasuries has risen to $1.65 trillion.

Despite t being downgraded to AA+ by Standard and Poor’s (S&P), the Fed still is treating U.S. Treasuries as if they were risk-free. After the nation suffered the worldwide humiliation at the hands of S&P, the Fed boldly proclaimed that “For risk-based capital purposes, the risk weights for Treasury securities and other securities issued or guaranteed by the U.S. government, government agencies, and government-sponsored entities will not change.”

That’s comforting.

Nonetheless, a Greek default may be just the shock the rest of the developed world needs to get its act together and to stop providing unrestrained financing to debt-addled governments.

After all, how can free markets ever compete with the limitless financing regime that governments enjoy today? There is no constraint on government expansion, but very real constraints on the private sector. A default in Greece may therefore be a blessing in disguise, helping other countries to get their fiscal houses in order — and the real economy back on track.

Bill Wilson is the President of Americans for Limited Government. You can follow Bill on Twitter at @BillWilsonALG.