By Bill Wilson — “We do not have an immediate debt crisis.”

That was House Speaker John Boehner’s take on the rapidly growing $16.75 trillion national debt, speaking on ABC’s This Week.

He went on to suggest that “we all know that we have one looming. And we have one looming because we have entitlement programs that are not sustainable in their current form. They’re going to go bankrupt.”

When asked when the crisis might be, the House Speaker acknowledged, “Nobody knows where this is. It could be a year, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years.” He didn’t know, but still insisted despite the uncertainty that “it’s not an immediate problem.”

Where’s the urgency? On one hand, his statement appears to wreck any possibility for something to get done this year to dramatically reduce spending beyond sequestration.

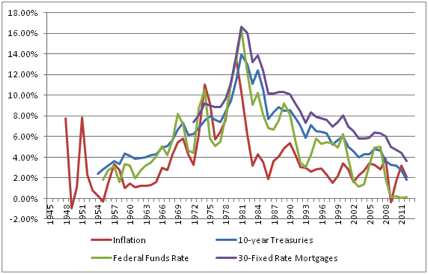

On the other, if by that he means it may take a long time before inflationary forces reassert themselves and for interest rates to significantly rise, ultimately making it difficult or impossible to service the costs of our skyrocketing debt, then certainly that appears to be true.

A word of caution, however. If we wait until rates rise to begin to finally address our fiscal problems, we will certainly have waited too long. By then, it will be too late. Today, the seeds are already being laid for future inflation.

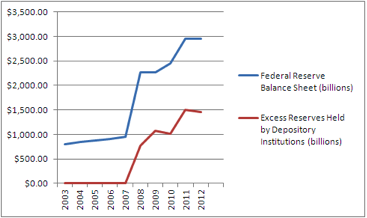

We all know the story well. With unprecedented quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve, when that money eventually floods the economy, we will experience harsh inflation.

Then interest rates will have to rise, pulverizing taxpayers with a debt that cannot be refinanced let alone be repaid. For every point of additional interest we must pay, payments to our creditors will rise by $167 billion.

Now, as quantitative easing enters its sixth year, economic growth still appears sluggish, and with it core inflation less food and energy, which have seen price increases in recent years. So, what gives?

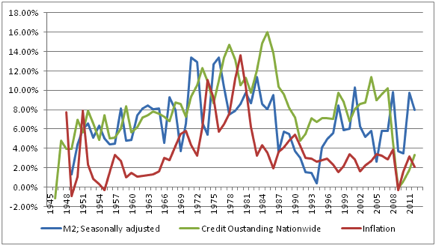

Again, the short bout of inflation in the late-1980s lagged behind another credit explosion. In the 2000s inflation was just starting to tick upward into higher territory when the housing bubble collapsed, taking the economy and inflation with it.

For now, so long as credit creation remains subdued, so will inflation. And even after borrowing begins growing robustly again, as it eventually will, it could take several years before it results in much higher price inflation.

But once it does, watch out. Because interest rates, including those at which the government borrows, do tend to follow inflation — as they must in order to rein it in.

So far, the impact appears to have been muted as banks stockpiled the quantitative easing given by the Fed in the form of unprecedented excess reserves amid low demand from consumers to go deeper into debt.

Additionally, the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency results in increased demand for dollars overseas, which has the effect of keeping domestic inflation tame.

If history serves as any indication, credit expansion sooner or later will restore its robust 7.9 percent historical trend upward, and along with it the growth of the monetary base, which has averaged 6.6 percent growth over the years.

Once these forces reassert themselves, the longer they are unimpeded by any asset bubble collapses, like housing, the greater the risk for a sudden spike in inflation becomes, and with it, a sharp rise in interest rates.

Mr. Boehner is correct that we have a debt crisis looming, which makes extremely disappointing his decision this year not to use either the continuing resolution or the debt ceiling as leverage to get real reforms enacted — such as the House Republican balanced budget plan. In a recent interview with Sean Hannity, he took all of those options off the table, saying, “It is very difficult to impose our will on them,” referring to the Democrat-controlled Senate and White House.

In the ABC News interview, the House Speaker criticized Barack Obama for basically saying that “we don’t really need to do anything at this point. And I would argue that we do need to do something.”

Yes, Mr. Boehner, we do need to do something. So do it now — before it is too late and interest rates really do rise, burying us under a mountain of debt that cannot be repaid, making the crisis in Europe look like a sideshow.

Bill Wilson is the President of Americans for Limited Government. You can follow Bill on Twitter at @BillWilsonALG.