In its June 25 in Shelby County v. Holder landmark ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated Section 4 of the longstanding Voting Rights Act of 1965. In the nine states affected, this is a major change in the law.

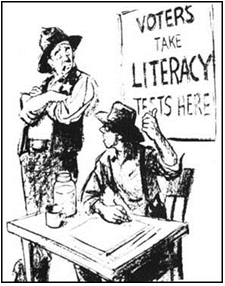

In responding to the ruling, ALG President Nathan Mehrens stated, “The Voting Rights Act of 1965 implemented the 15th Amendment provision empowering Congress to enact legislation enforcing the protection against voter discrimination on the basis of race. It was enacted during a time of literacy tests and other Jim Crow laws that have long since been banned nationwide. In effect today, the Act gave the Justice Department de facto veto power over nine state legislatures’ enactments of any changes to election law that states would otherwise have had the power to put into effect.”

The Voting Rights Act was created to deal with the racial discrimination in the 1950s and 1960s that kept many African Americans from voting. It has two sections which are pertinent to the court case: Section 4 and Section 5. Section 4 establishes the formula for which localities need to file for preclearance with the Justice Department to change their voting laws, while Section 5 contains the preclearance requirement.

The Section 4 formula according to CivilRights.org “applies Section 5 to any state or county where a literacy test was used as of November 1, 1964, and where a participation rate of under 50 percent by eligible voters in the 1964 presidential election showed the test had a racially discriminatory basis. Later amendments to the Act included the years 1968 and 1972 in the coverage formula.” In practice this covered “16 states: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Texas; and most of Virginia, 4 counties in California, 5 counties in Florida, 2 townships in Michigan, 10 towns in New Hampshire, 3 counties in New York, 40 counties in North Carolina, and two counties in South Dakota.”

The Section 5 requirement, according to the U.S. code, applied to “Any voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting that has the purpose of or will have the effect of diminishing the ability of any citizens of the United States on account of race or color.” In practice this means every change to voting law including district lines, polling locations, dates, registration procedures, eligibility requirements, etc. needed to be cleared through the U.S. Department of Justice before they could be approved.

The case arose when one of the affected counties requested “a declaratory judgment that sections 4(b) and 5 are facially unconstitutional, as well as a permanent injunction against their enforcement,” according to the ruling. In a 5-4 decision, Chief Justice John Roberts ruled that Section 4 was unconstitutional, while Section 5 remained constitutional.

The court noted that in the 2012 presidential election, “African-American voter turnout exceeded white turnout in five of the six states originally covered by Section 5, with a gap in the sixth of less than one half of one percent.” In essence Barack Obama did so well with African American turnout that President Obama’s campaign showed that the equation is fundamentally flawed.

The majority opinion also noted that in the first decade of enactment the “Attorney General objected to 14.2 percent of proposed voting changes… In the last decade before reenactment, the Attorney General objected to a mere 0.16 percent.” The court also noted the incredible increase in the number of African American elected officials in the impacted states. The court found that on every front, there was little need for the Voting Rights Act in the respective states. The court also stated that the formula for the Voting Rights Act had not been adjusted since its enactment in 1965, and was clearly outdated for a rule that was reauthorized in 2006 for 25 years through 2031.

While the court left the Section 5 prefiling requirements in place, by removing the Section 4 formula defining who needs to prefile, it rendered the prefiling requirement meaningless. This was not lost on Justice Clarence Thomas, whose concurring opinion strongly called for striking down Section 5 as well. Under the doctrine of equal sovereignty, the idea that Congress could target certain states with a law would be found unconstitutional in almost every other situation. Not invalidating Section 5 also violates well established principles of severability that a law made inoperable by invalidating one section is not severable from the unconstitutional section and thus must be thrown out as well.

The decision to invalidate only Section 4 creates an interesting political situation where those who believe in protecting the Voting Rights Act can restore the prefile requirement if it creates a modern equation for what localities the requirement applies to.

Fascinatingly, Congress’s failure to act is what led to the invalidation. In the last challenge to the Voting Rights Act, the Supreme Court warned Congress to update the equation. Congress did nothing. This inaction is something that the court reminded Congress of in the opinion.

The last section of the Court’s opinion is the judicial version of throwing the Voting Rights Act ball back across First Street N.E. to Congress. Emphasizing that invalidating a federal law is one of its most serious responsibilities, and that it “do[es] not do so lightly,” the Court makes clear that in its view, only Congress is to blame here. Four years ago, it warned Congress that the constitutionality of the law was in doubt: “Congress could have updated the coverage formula” then, but it failed to do so. “Its failure to act,” the Court explains, “leaves us today with no choice but to declare [the coverage formula] unconstitutional.”

The practical implications to striking down the Section is simply one of ease. Efforts to restrict minorities access to voting have disappeared as the decades progressed. The result was that the act led to long delays for states and localities that were trying to make regular simple changes to the voting procedures.

However, the fact that iconic legislation that protected minorities in the 1960s was rendered impotent by its own success has many on the left enraged. Strong calls are being made for congress to create a new formula, others elected Democrats are using racial slurs against Justice Thomas, and yet others are pushing for a constitutional amendment to ensure the freedom to vote for all, seemingly ignorant of the 15th Amendment’s clear protections.

If the Democrat response to the Citizens United ruling is any indicator, we can expect many Democrats to campaign for Congress in 2014 on “restoring” the Voting Rights Act, and continue to talk about this issue at least leading into the 2016 presidential election. While the respective localities no longer need to follow the prefile requirement, we can expect Republicans to be demonized as wanting to disenfranchise minorities if they don’t support resurrecting Section 4 of the Voting Rights Act.

This is a political situation Chief Justice Roberts created by rendering Section 5 meaningless instead of simply invalidating it.

With Congress unlikely to act on the Voting Rights Act, it will be interesting to see how long it takes for the Democrats to stop using this as a wedge issue after minorities continue to vote in large numbers and succeed at the ballot box. Time will tell.

Willie Deutsch is Editor-in-Chief for NetRightDaily.com, and Social Media Director for Americans for Limited Government. You can follow him on twitter @williedeutsch.