Deflation? No, not footballs.

In this case, a growing number of economic observers are becoming concerned about falling prices, in the Eurozone, the Pacific, and elsewhere — and what it means for the global economy.

In the 1930s, falling prices were a scourge. Assets became less attractive over time, since they might be cheaper to get in the future, and so it forestalled purchases. Meanwhile, the economy failed to recover, despite the collapse of the international gold standard and the easing of monetary conditions that brought.

No matter what central banks conjured up, the economy kept on sinking.

So, are we in the same situation today?

For certain, prices are slowing in the Eurozone, only growing at an annual rate of 0.6 percent in 2014, according to Eurostat. So spooked were policy makers, that the European Central Bank is firing up the printing presses, promising monthly purchases of assets totaling €60 billion.

And in Japan, where the economy has not grown at all for over 20 years. Since the beginning of 2012, the Bank of Japan has more than doubled the amount of government securities it holds.

Similar fears provoked the U.S. Federal Reserve to engage in unprecedented asset purchases of U.S. treasuries and mortgage-backed securities since the financial crisis began in 2007, totaling more than $3.5 trillion.

Despite the easing, prices in the U.S. most recently dropped 0.4 percent in December. But the decrease has been led primarily by a 9.4 percent decline in gasoline and a 7.8 percent drop in fuel oil.

So, the current slowdown may just be the price of oil correcting itself, a view taken by Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen who says the current price drops are only “transitory.”

On the other hand, there is no question that prices have been trending downward for two decades in the U.S., Europe, and Japan — along with nominal economic growth and jobs growth.

But the real downward pressure may be coming from a different source, namely, the decline of the working age population. In Europe, the number of people aged 16-64 has only increased an average annual percent of 0.31 percent since 1996. In Japan, as the workforce there rapidly ages, the population aged 15-64 has been in outright contraction, decreasing at 0.52 percent a year.

The U.S is slightly better, with the working age population growing at about 1.07 percent a year.

Nonetheless, a shrinking number of people entering working age does appear to have a major impact on everything else, largely because of lower demand for goods and services, credit, and everything else.

In Japan, the quantitative easing does appear to have had some temporary impact, spiking inflation in the past twelve months by 2.4 percent, according to the Statistics Bureau of Japan. Also, in 2013, nominal economic growth poked upward at a whole 1 percent (believe it or not, for Japan that’s actually quite significant).

However, that trend may already be reversing, as in the third quarter of 2014, nominal growth in Japan fell 0.8 percent.

So, despite all of the easing by the Bank of Japan, it is not enough to overcome the overall demographic decline there. The central bank cannot print customers, apparently. All it can do is prop up asset prices which might have some impact on the economy, but then only temporarily.

Which may be the lesson to be learned. Throwing money from helicopters does not really have much of an impact over the long haul if nobody’s around to spend it. Just as there may be a “demographic dividend” when working age populations are growing, there appears to be a commensurate decline when they are not. Long-term, couples may start deciding to have more children.

Until then, the world might need to start getting used to slower growth, weakening demand, and yes, falling prices. What is clear is that no amount of quantitative easing has been able to stop the economic slowdown worldwide.

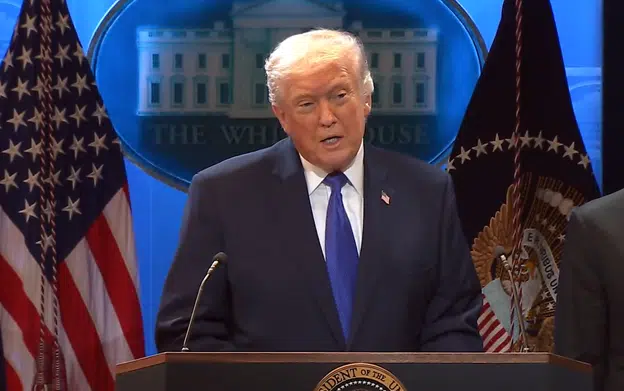

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.