Being first has its advantages.

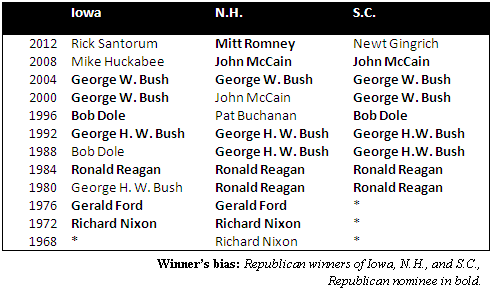

Since the advent of the Iowa caucuses in 1972 and the South Carolina primary in 1980, the “first in the nation” political contests, including the New Hampshire primary which dates back to 1916, have had an uncanny knack of declaring who the nominee for President will eventually be, particularly on the Republican side of the aisle.

In fact, you cannot find a Republican nominee for president in modern history that did not win either Iowa or New Hampshire. For its part, “first in the south” South Carolina has predicted the ultimate nominee every year except for 2012, when it selected Newt Gingrich.

In years without a sitting Republican president on the ballot — 1980, 1988, 1996, 2000, 2008, and 2012 — Iowa and New Hampshire have delivered opposite results. Neither chose the same candidate.

In those years, Iowa correctly chose the party’s ultimate nominee in 1996 and 2000, Bob Dole and George W. Bush, respectively. New Hampshire took the other 4: Ronald Reagan in 1980, George H.W. Bush in 1988, John McCain in 2008, and Mitt Romney in 2012.

South Carolina beats them both, having chosen the eventual nominee 5 out of 6 times. But, it is worth noting that coming slightly later in succession, South Carolina voters have the benefit of seeing the other early contests play out.

The one time South Carolina got it wrong, in 2012, happened to be a year when it did not select one of the winners of Iowa or New Hampshire.

So, Iowa and New Hampshire choose the players and breaks the field down, but South Carolina tends to decide the outcome of the GOP contest.

The importance is shared on the Democrat side, too, but to a lesser extent as there are a couple of notable exceptions. Bill Clinton managed to secure the nomination in 1992 without winning either Iowa or New Hampshire, and so did George McGovern back in 1972.

Still, two-thirds of the years where no incumbent Democrat was running — 1976, 1984, 1988, 2000, 2004, and 2008 — the nominee had won either Iowa or New Hampshire.

With more than three decades of compelling evidence, then, a virtual monopoly emerges for Iowa, New Hampshire, and South Carolina — which constitute less than 4 percent of the nation’s population — selecting the Republican presidential nominee.

Call it winner’s bias. Voters want to associate with a winner, and they do not wish to waste their votes on someone whom they perceive cannot win.

Consider the prospect of placing a sizeable bet on a horse — after the race has already begun. The further behind in the race the stallion is, the greater risk he or she will never catch up. If the lead appears to be insurmountable, comparatively fewer bets would be made.

Meaning the later the primary or caucus occurs in the process, the less important it becomes to the overall outcome. And the choice becomes less ideological since perceived electability, based on prior results, becomes a primary concern moving forward.

The winner’s bias then becomes undeniable.

Those later voters also get comparatively fewer choices, since as time goes on and resources are exhausted, more candidates tend to drop out of the race.

Meaning, the current nomination process may have some merits, but offering a wide range of choices to 96 percent of voters is not one of them.

Robert Romano is the senior editor of Americans for Limited Government.