“As I predicted, Jay Powell and the Federal Reserve have allowed the Dollar to get so strong, especially relative to ALL other currencies, that our manufacturers are being negatively affected. Fed Rate too high. They are their own worst enemies, they don’t have a clue. Pathetic!”

That was President Donald Trump’s reaction on Twitter after U.S. manufacturing had its worst showing in 10 years as the Institute for Supply Management (ISM) manufacturing index came in with its lowest reading since 2009 at 47.8. Readings below 50 signify a contraction.

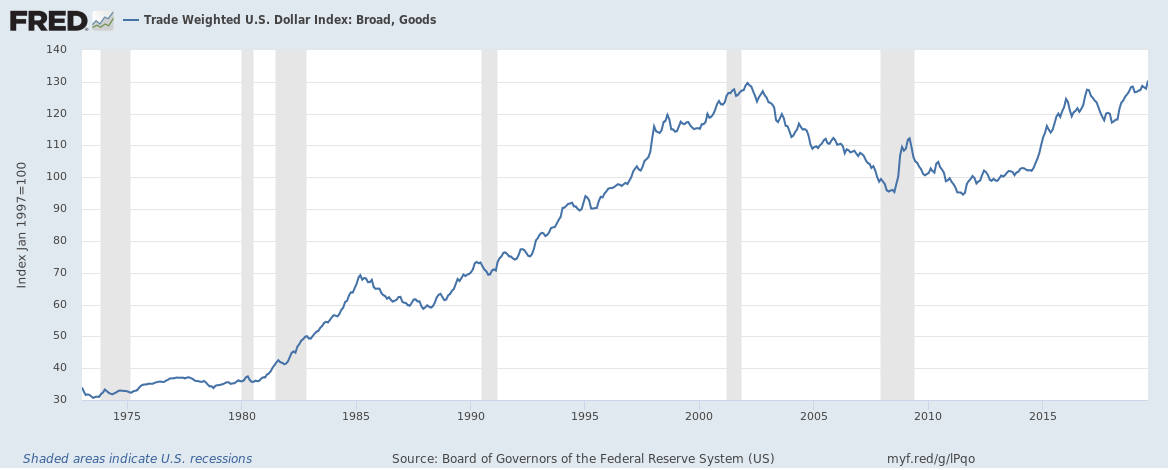

In the meantime, the U.S. Dollar Index shows that, on a broad trade-weighted basis, it has never been stronger at over 130, despite two consecutive interest rate cuts to the federal funds rate by the Federal Reserve. The strong dollar makes U.S. exports more expensive and imports cheaper.

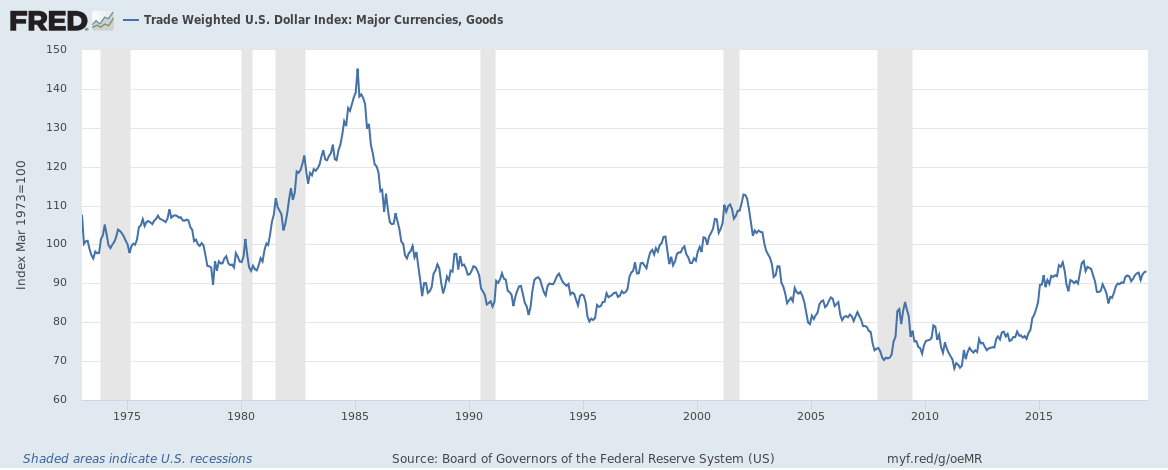

In his tweet, Trump makes an important distinction between the dollar index relative to a wider basket of currencies, as above, which includes the Euro Area, Canada, Japan, Mexico, China, United Kingdom, Taiwan, Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Brazil, Switzerland, Thailand, Philippines, Australia, Indonesia, India, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Sweden, Argentina, Venezuela, Chile and Colombia, and the more traditional, “major” currencies index of the dollar versus the Euro Area, Canada, Japan, United Kingdom, Switzerland, Australia, and Sweden, which appears to show relative weakness compared to prior decades.

As this author noted last month, a strong dollar on the broad index, not the major currencies index, tends to coincide with drops in U.S. exports per an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau and Federal Reserve data. What is telling is that this correlation long predates President Trump’s tenure in office or any trade standoff with China, including the tariffs currently being levied.

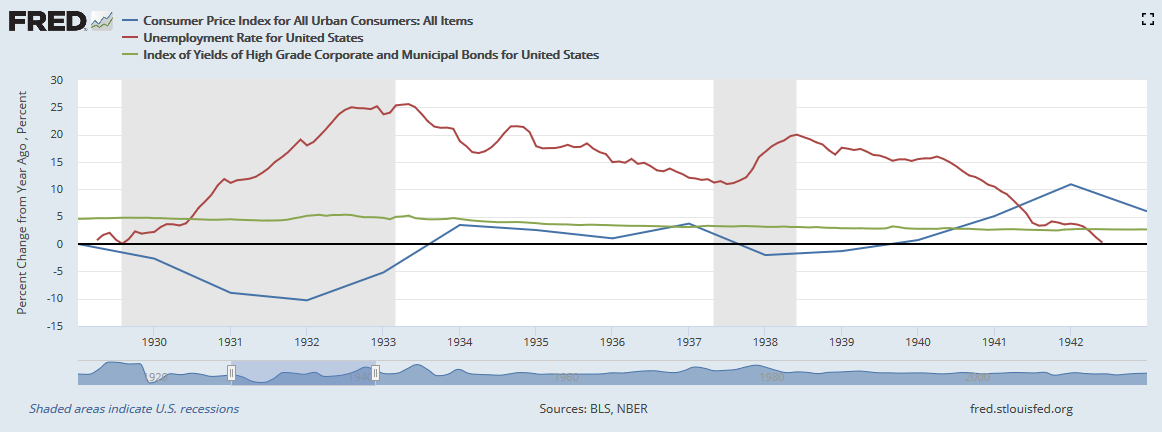

Therefore, with the dollar having never been stronger in modern history relative to the wider basket of currencies, the weak manufacturing reading from ISM is not at all surprising. It is what economists predict would happen based on past experience, including the Great Depression, as nations were coming off the interwar gold standard.

In the 1930s, the U.S. remained with the stronger dollar pegged to gold all the way until 1933 even as deflation reigned supreme — Great Britain had withdrawn from gold in 1931 — and the Hoover administration sat by idly as unemployment soared, reaching 11.2 percent by the end of 1930, up to 19.2 percent by the end of 1931, up to 25 percent in 1932 and peaked in March 1933 at 25.4 percent. It was not until after the U.S. departure from gold that the unemployment rate finally began coming down. A brief return to deflation again showed the very real danger of allowing the dollar to get too strong in 1938, when unemployment spiked again, before returning to full employment as the U.S. entered World War II.

Meaning, President Trump is right. The dollar, if allowed to remain too strong for too long by the Fed and, ultimately, the U.S. Treasury, can absolutely make any economic slowdown worse. Much worse. All of which makes the President’s commentary on this topic timely and refreshing.

Unlike his predecessors, Trump is a hands-on President, well-advised and fully aware of the devastating impacts that competitive devaluations have had on the U.S. economy and the American people if they are left unchecked.

In fact, U.S. dollar exchange rates to the Chinese yuan and to the euro and the Mexican peso — some of our largest trading partners — are at or are reaching highs. And throughout the 2000s, comparatively weak currencies overseas led directly to the shift in manufacturing production away from the U.S. as economic growth slowed, not topping 4 percent since 2000 and not topping 3 percent since 2005.

Now, some might look at those developments and simply ascribe them to free market movements and say the solution to a non-problem is to do nothing. But this would ignore, on the yuan, the fact that China does not adhere to floating exchange rates, instead it sets a comparatively weak fixed standard to the dollar.

It would also ignore that all these countries’ central banks are intervening heavily in foreign exchange markets. The biggest traders sometimes can be the central banks, which are government organs, making the competitive devaluations acts of economic war — a dagger pointed at the heart of the U.S. economy and American workers.

The question is what the Federal Reserve and the Treasury, in tandem, are able and willing to do about it. The federal government is not powerless. It could wield the Exchange Stabilization Fund and engage in so-called warehousing of foreign currencies.

In late July, CNBC reported the White House discussed the issue but ruled out — for now — any intervention. U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin told CNBC his preference for a strong dollar: “a stable dollar is very important. And over the long-term period of time — again, the long term — I do believe in a strong dollar.”

But those are not the same thing. The Fed’s dual statutory mandate is to maintain price stability and full employment. The dollar being too strong can run opposite to both. Just as the dollar being too weak can cause inflation, when it gets too strong it can have a deflationary impact on prices and even cause a recession. That’s not price stability, and clearly, it currently is not helping the U.S. economy remain competitive in the near-term.

Moreover, the case that the dollar’s relative strength since the late 1990s compared to prior decades (even as it was weakening from its unprecedented highs hit in 2002 has been helpful to the U.S. economy — following the dotcom bust, the financial crisis, Great Recession and non-recovery of the Obama years — is questionable.

Besides intervening in foreign exchange markets, President Trump and U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer are doing everything else in their powers including engaging in urgent talks with our trading partners and, when necessary, deploying other countermeasures including tariffs when they refuse to come to the table and deal fairly. But that has its limits, as the U.S. learned in the extreme case of the 1930s. Again, the Hoover administration ignored currency and focused singularly on trade tariffs, and look at what happened. The problem was not the tariffs, it was that the dollar was neglected.

Trump is different. For once, the American people have a President who is not going to sit by idly while foreign governments engage in economic predation, whether on trade or competitive currency devaluations. It’s about time. But at some point — it may not be immediately — if the goal is fair and reciprocal trade, the currency issue needs to be addressed. Something’s got to give.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.