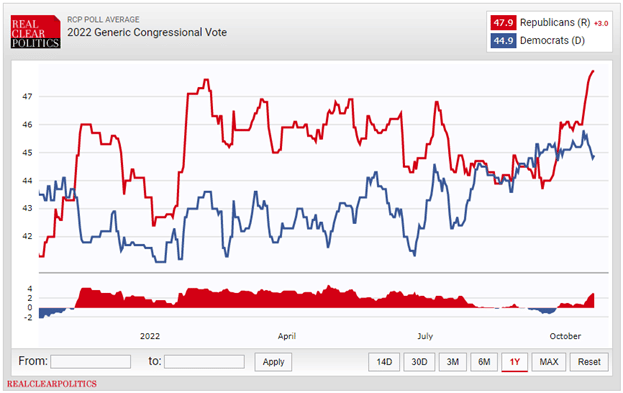

The 2022 U.S. Congressional midterm elections are entering their home stretch and, as usual, the opposition party that last lost the White House in the presidential election—in this case, the Republicans—have jumped out to a big lead in polls, this time a 3-point spread, according to the latest average of national polls by RealClearPolitics.com, 47.9 percent to 44.9 percent.

The shift in the race for Congress, where it appears highly likely Republicans will pick up at least the six seats needed for a House majority—the opposition party picks up seats about 90 percent of the time in a Congressional midterm election, and in those cases, about 35 seats—comes as high inflation and concerns over the war in Europe are weighing on voters.

The latest New York Times/Siena poll taken Oct. 9 to Oct. 12 shows that the economy (26 percent) and inflation (18 percent) combine for the top issue in the election, or 44 percent, while concerns like abortion after Roe v. Wade was overturned only account for 5 percent of voters, including just 9 percent of female voters. It also gave Republicans a four-point lead over Democrats, 49 percent to 45 percent, in the generic ballot.

And the latest Economist/YouGov poll shows that, thanks to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a full 50 percent of voters say that the likelihood of nuclear war is greater now than it was five years ago, including 38 percent who say that it is either very likely (7 percent) or somewhat likely (31 percent) that Russia will use nuclear weapons in Ukraine in the war. That poll has Republicans up one-point in the generic ballot, 47 percent to 46 percent among likely voters.

Usually, in a recession, voters will turn against an incumbent party, often resulting in defeat, particularly in presidential elections but also midterms, like Herbert Hoover’s 1930 midterms as the Great Depression took hold, where Republicans lost a whopping 52 seats in the House, barely holding onto what had just recently been more than a 100-seat majority, 270 seats to 164 seats.

And in wars, voters can sometimes experience a “rally around the flag” effect, as in the 2002 Congressional midterms where George W. Bush and Republicans actually picked up seats in the House despite being the incumbent party as they forced tough votes authorizing the use of military force in Iraq that split Democrats.

So, there could be two potential predictive models—economic model and the “rally around the flag” model—colliding with one another on Election Day, but on the other hand, it is hard to see what political benefit President Joe Biden and Congressional Democrats have obtained from the war in Ukraine, which has exacerbated the post-Covid global supply crisis, causing rampant energy inflation as Russia oil and gas exports have been restricted via sanctions.

Besides the $6 trillion Congress and the Federal Reserve borrowed and printed, respectively, for Covid, which was already pushing inflation above 5 percent since June 2021, the war in Ukraine, which began Feb. 2022, has been a major contributor to the inflation that has voters so irate.

It is possible that the prospect for another world war, combined with President Biden, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky all discussing the use of nuclear weapons and Armageddon openly, has frightened voters, who might be wondering how this mess could have been avoided. If a logical potential outcome of rallying around the flag is nuclear war, voters might be more reluctant to support that war because they don’t think it’s survivable.

Probably because U.S. nuclear doctrine since the end of Harry Truman’s second term of office has always been something along the lines of the idea that a nuclear war cannot be won and so must never be fought, which President Biden also expressed recently. If not war, then, diplomacy remains the means of resolution. Perhaps that is what voters are hoping for.

In fact, whenever this issue ever came up during the Cold War with the Soviet Union, it was always resolved somehow via diplomacy, especially beginning in 1962 with the Cuban Missile Crisis, which required concessions on both sides to diffuse, in that case by removing missiles from Cuba and Turkey. Surviving that crisis led to an age of nuclear summits across presidents of both parties and the ABM, SALT I, SALT II, INF, START I, START II and New START treaties.

Instead, voters have to consider what appears to be a rush to war they are not being asked to opt into. Biden hasn’t made the case, and has taken troops in Ukraine off the table in a bid to tamp down escalation.

In 1962, there is some thought that John Kennedy and Democrats avoided a midterm wipeout because of the crisis — they only lost four seats that year — but that was only achieved after the U.S. naval blockade of Cuba visibly managed to turn Soviet ships bearing more nuclear weapons from making their way to the island. There was a sense of relief that a global calamity had been averted. Whereas today, the crisis has been ongoing for months and so long as the war continues and will apparently not be resolved anytime soon. If so, voters might do what they usually do in midterms and say, “Time for a change.”

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.