The U.S. economy shed 328,000 jobs in October, raising the national unemployment rate to 3.7 percent as inflation cooled to 7.7 percent annualized, the latest employment and price data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) shows.

This is what usually happens at the end of economic cycles after peak employment has been reached and the economy overheats. Prices get too high from the inflation and as consumers spend more on food and energy, they spend less on other items, including putting off larger purchases for later, resorting to credit cards for basic household needs until finally, consumer spending contracts along with prices.

That’s when the recession strikes. Businesses, seeing weaker demand, first stop hiring and then begin laying off employees.

Sure enough, job openings are down 1.1 million from their March 2022 peak of 11.8 million.

And this is the third time this year that BLS has recorded jobs losses in the household survey: 353,000 in April, 315,000 in June and now 328,000 in October. Those losses were more than offset by gains in all the other months.

Historically, drops in inflation have coincided with increases in unemployment, the most extreme example being the Great Depression, when deflation consumed the U.S. and global economy as the interwar gold standard fell apart at the seams.

Back then, the U.S. dollar was way too strong as foreign trade partners like Great Britain moved off of the gold standard, artificially strengthening the dollar and sending the economy into a crash landing. The Great Depression dragged on for years not because of government intervention or tariffs per se, but because of the failure to recognize the adverse impact of keeping the dollar exchange rate to gold so high while the rest of the world was engaged in competitive devaluation and retiring the interwar gold standard.

Deflation in the U.S. began after the great inflation of World War I and the ensuing credit expansion, had a brief respite in the 1920s before beginning again in 1927. It then slowed in 1929, and then went crazy starting in 1930 as banks began failing en masse. Inflation was marked at -2.7 percent in 1930, -8.9 percent in 1931, -10.3 percent in 1932 and -5.2 percent in 1933.

As that occurred, unemployment skyrocketed, reaching 11.2 percent by the end of 1930, up to 19.2 percent by the end of 1931, up to 25 percent in 1932 and peaked in March 1933 at 25.4 percent.

The United Kingdom had a similar experience of deflation following World War I, with unemployment rising dramatically in 1921 to 11 percent before dropping and again rising in 1930 to 11 percent. The UK quickly came off the gold standard in 1931, after which unemployment peaked in 1932 at 15 percent, before slowly coming back down.

It was not until Franklin Roosevelt ended the interwar gold standard in 1933 that some relief was felt in The U.S. as unemployment began collapsing down to 11 percent by 1937 before spiking again in the 1937-38 recession as deflation ensued again. Ultimately, the ongoing problems were not fully alleviated until the massive mobilization of World War II.

During Covid, a similar pattern emerged as the global economy shut down and the value of the dollar soared to its highest levels on record at the time, and 25 million jobs were lost. So, the Fed took interest rates to near-zero percent and central banks and financial institutions purchased a ton of U.S. treasuries to shore up the U.S. economy amid a $6 trillion spending and printing binge. The dollar weakened, and unemployment collapsed in record time.

We halted production and expanded the money supply dramatically at the same moment — too much money chasing too few goods. What else were prices supposed to do?

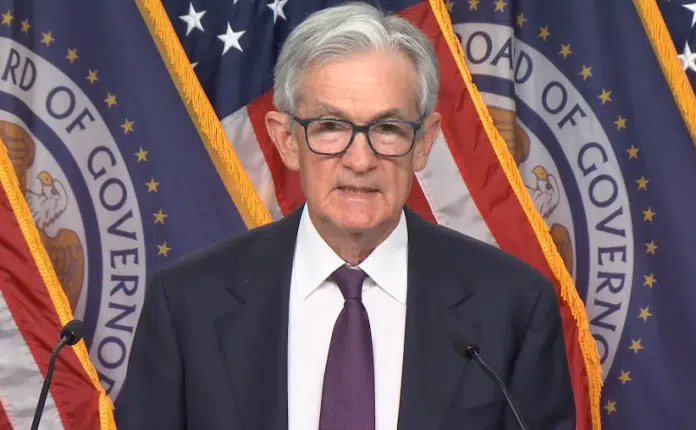

Now, after all the printing, and the high inflation, the Fed has hiked interest rates to 3.75 percent to 4 percent, with more hikes on the horizon to fight the inflation, stabilizing the M2 money supply, albeit at a much higher level, and which could even begin contracting on an annualized basis for the first time since — well, ever. It’s never contracted in the entire history of the Fed’s dataset going back to 1959.

As interest rates have risen, combined with the ongoing, Covid-induced global supply crisis and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, so too has the value of the U.S. dollar risen against foreign trade partners, sending the value of the dollar even higher than during Covid, only coming off those highs in the past few weeks.

But with more interest rate hikes to come to combat the inflation as global production still lags behind demand, there appears to be no offset to prevent the dollar from getting even stronger than it already is.

Could all that spark deflation?

One looming factor to consider are the current labor shortages as Baby Boomers retire en masse. There are still 10 million job openings — and now way to fill them. Meaning, the production shortfalls we are experiencing will be ongoing, and meeting demand will continue to be a challenge.

That is, until employers give up on expansion and the layoffs really begin in earnest. It could be somewhat muted by the retirement wave — in advanced economies like Japan with aging populations peaks in the unemployment rate during recessions have tended to be much lower than in the U.S. — but all of that unemployment is still on the horizon. The rate is already increasing, but by how much remains to be seen.

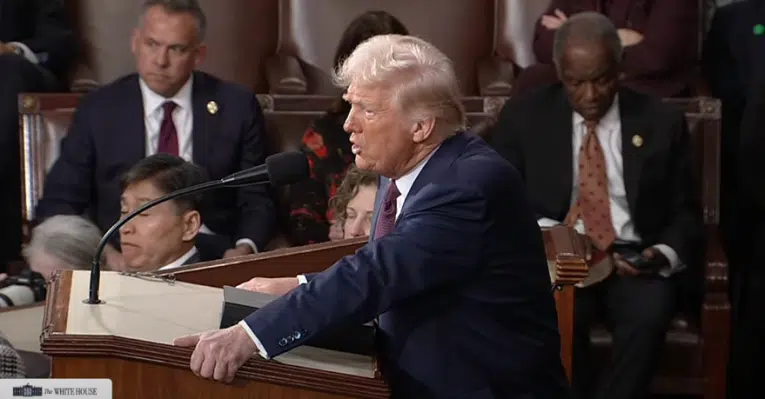

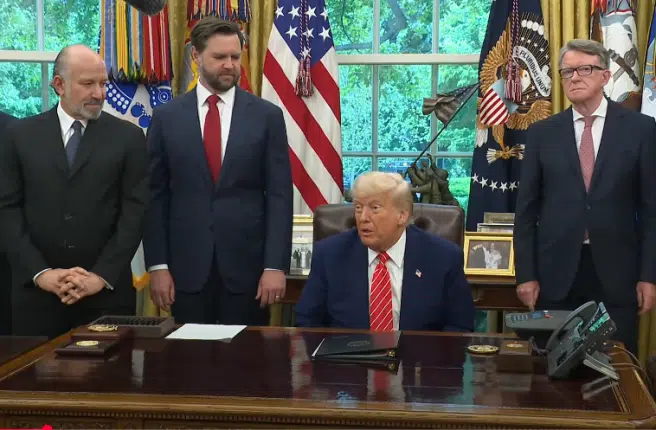

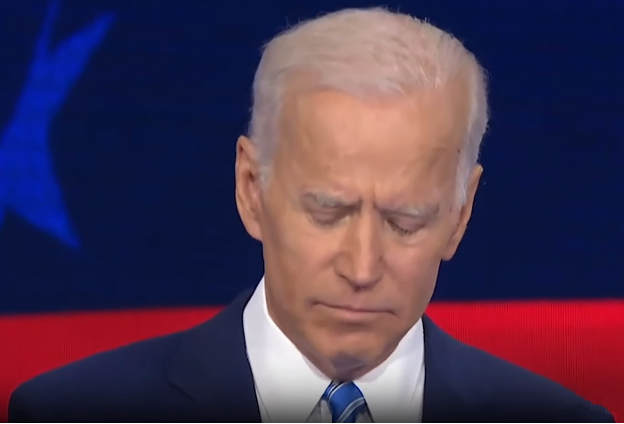

Politically, in the U.S., recessions have often been a catalyst for change, resulting in one-term presidents including Herbert Hoover in 1932, Jimmy Carter in 1980, George H.W. Bush in 1992 and Donald Trump in 2020. To fight the recession and unemployment, President Joe Biden will be tempted to weaken the dollar and stimulate the economy via more government spending, and the Fed via quantitative easing, at least until after 2024.

With Republicans taking control of the House in the 2022 midterms, big spending bills might not be possible as gridlock ensues, thereby controlling the growth of the money supply on the fiscal side.

It’s a crossroads. Down one road is recession, and down the other is more inflation, leading to another recession, perhaps larger, even further away.

Choose your poison.

This could result in political pressure from the White House on the Fed to lower interest rates and purchase more treasuries as unemployment rises. For now, the Fed seems to be saying it will cross that bridge when it gets to it, instead focusing on taming the inflation, even if it means a recession now rather than later. Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.