The Federal Reserve has once again hiked the federal funds rate that it controls in its Feb. 1 meeting of the Board of Governors, now reaching 4.5 to 4.75 percent, as consumer and producer inflation, which remains elevated, continues to cool off its highs in 2022.

And the rate hikes are not over yet, as the central bank said it “anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range” could be necessary going forward.

According to the central bank’s statement, “the Committee decided to raise the target range for the federal funds rate to 4-1/2 to 4-3/4 percent. The Committee anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time.”

Put simply, there aren’t too many other ways to destroy the money after the massive monetary expansion that occurred in response to the Covid pandemic in 2020, where more than $6 trillion was spent, borrowed and printed into existence at the same time as halts to global production and economic lockdowns that exacerbated the ongoing supply crisis.

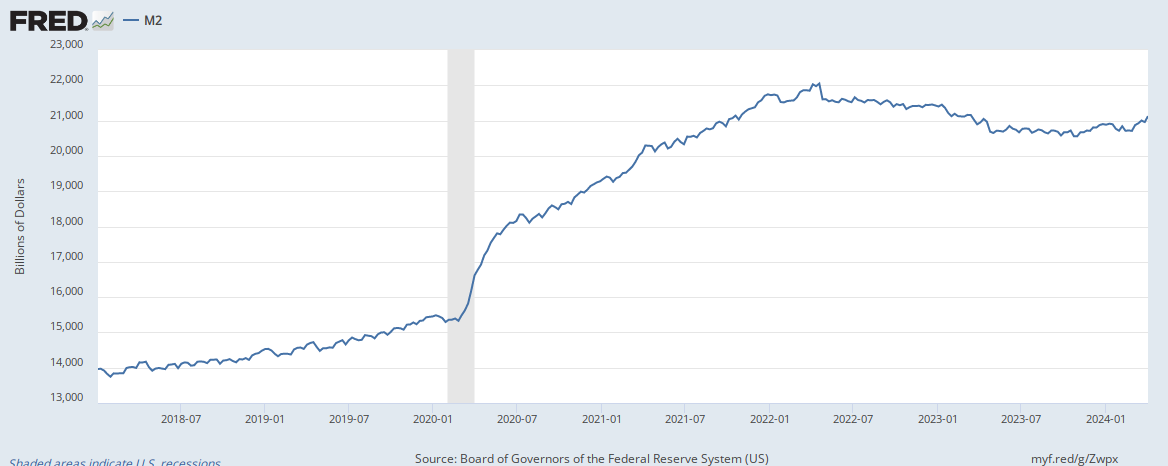

As a result the M2 money supply increased dramatically from $15.3 trillion in Feb. 2020 to a peak of $22 trillion by April 2022, a massive 43.7 percent. Increases like that usually only happen during wartime such as World War I or World War II to accommodate rampant deficit spending at a time when global financial markets tend to be disrupted.

It was too much money chasing too few goods, quite literally, leading to the inflation spike, where consumer inflation reached 9.1 percent in June 2022, and is at 6.5 percent now, and producer inflation reached 11.7 percent, and is now down to 6.2 percent in March 2022.

In fact, by the time Russia invaded Ukraine in Feb. 2022—further worsening global supply issues—consumer inflation was already north of 7.5 percent and producer inflation had already reach 10 percent.

And, it wasn’t until the invasion that the Fed decided to finally start hiking U.S. interest rates.

In any event, thanks to the rate hikes—which raise the interest rates that banks borrow at, which are passed onto consumers via even higher rate hikes, such as 30-year mortgages which peaked at 7 percent in Oct. and Nov. 2022 and are now down to 6.1 percent—the M2 money supply has actually shrunk by $724 billion, a 3.2 percent decrease, to $21.3 trillion.

Similarly, the Fed has been reducing some of the quantitative easing that was put into effect for Covid, selling off some of its treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, and therefore reducing its holdings by $391 billion the past year.

And this process will be ongoing, the Fed promises. On future rate hikes, which again the Fed anticipates, the central bank promised to keep an eye on overall tightening of money: “In determining the extent of future increases in the target range, the Committee will take into account the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments.”

And it will continue selling its treasuries and mortgage-backed securities: “In addition, the Committee will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities, as described in its previously announced plans.”

All of which should provide more than ample wiggle room as the U.S. economy, especially should unemployment begin to rise. As it is, the unemployment rate remains at historic lows at 3.5 percent, even as non-seasonally adjusted continuing unemployment claims has risen steadily to 1.9 million on Jan. 21 from its low of 1.2 million in Oct. 2022.

Since recessions usually follow periods of peak employment—and other indicators like the spread between the 10-year and 2-year treasuries remain inverted, which almost always signals a recession—it appears the Fed is anticipating a need to begin curtailing its tightening once inflation gets back under control, demand drops and unemployment could begin to rise.

However, with the Baby Boomers continuing to retire en masse, that could serve as a partial or significant anchor on the unemployment rate, similar to how the great wars did so simply by reducing the labor supply of able-bodied men. And given the way things are going in Ukraine, with the U.S. sending Abrams tanks after saying it wouldn’t because that might mean World War III, with the possibility of U.S. intervention in the war looming, that might end up happening anyway. Whether it’s a hard landing or a soft landing for the U.S. economy, as usual, stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.