There’s enough revenue to pay interest on the debt even if the $31.4 trillion debt ceiling is reached.

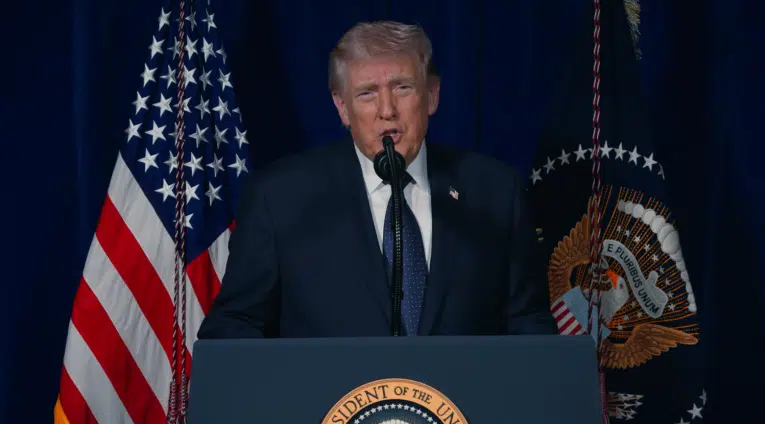

Meaning, if the U.S. defaults on the debt on June 1, it will be because President Joe Biden chose not to make principal and interest payments on U.S. Treasuries out of existing revenue, for which there is more than ample revenues to service and refinance up to the current debt ceiling limit, $31.4 trillion.

While gross interest owed on the debt in 2023 is $897 billion, a good chunk of that is owed to the Social Security, Medicare and other trust funds, which count as revenue, resulting in net interest of $665 billion.

Still the gross interest is the full amount owed, so $897 billion is the number to watch, but there is more than ample revenue at the U.S. Treasury to meet those obligations: some $4.8 trillion of taxes collected annually, according to the White House Office of Management and Budget.

There would still also enough revenue to meet Social Security ($1.346 trillion), Medicare ($821 billion), Medicaid ($608 billion) and defense spending ($800 billion). Between the gross interest and these programs, that’s about $4.47 trillion out of the $4.8 trillion of revenue.

It’d be tight, but there is enough revenue there to certainly meet the obligations for U.S. treasuries, and then key programs seniors depend on plus national defense. That is, if President Joe Biden chose to make payments to them on a continued basis while he and Congress were still negotiating an increase in the debt limit.

There would also be just enough to barely pay out food stamps ($183.7 billion) and veterans income security ($150 billion).

But that’s it. Everything else that would temporarily fall by the wayside, including non-defense federal agency budgets like the Department of Education, but also defense-related ones including the Department of Veterans Affairs. The truth is there are $6.37 trillion of outlays and on $4.8 trillion of revenues with which to work with when the debt ceiling is hit.

Alternatively, the federal government could still meet 100 percent of $897 billion owed in interest, refinance debt up to the limit, and then engage in a type of budget austerity with across the board budget cuts. In that scenario, every line on the budget would be paid with 87.7 percent what it was promised.

In essence, individuals, departments, agencies and contractors who receive government disbursements in some manner would have a 12.2 percent cut in those disbursements.

And there’s measures somewhere in between, where more than just interest is paid at 100 percent, thereby necessitating even larger cuts further down the line. That would be up to President Biden to decide.

That is, if he simply chooses not to deal with the U.S. House of Representatives and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), who, because of the unsustainable trajectory of federal spending and borrowing — the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) projects the national debt will reach $50.7 trillion by 2033 as Social Security and Medicare payments rocket skywards after the Baby Boomers are finished retiring — is using the debt ceiling as a means of negotiating a pared down discretionary budget with spending caps.

Under the House-passed Limit, Save, Grow Act, the national debt ceiling would be increased, and Congress would cut $4.8 trillion in deficits through 2033: $3.2 trillion from the discretionary spending caps, $460 billion from ending President Biden’s student loan forgiveness program, $569.5 billion from repealing the green energy subsidies from the Inflation Reduction Act and other legislation, $120.1 billion from implementing work requirements for food stamps and other welfare programs, $29.5 billion from budget rescissions from Covid and other spending, $3.4 billion from energy leasing and permitting provisions and $547 billion as a result of less interest payments owed thanks to cutting spending, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

And, believe it or not, this would only be the first step in getting our unsustainable spending and borrowing under control. Down the line, how best to shore up Social Security and Medicare are not even on the table. They’re not part of the current discussion. But one day they will need to be.

Unless Biden makes them a part of the discussion right now, but threatening not to make payments to them in the even if the debt ceiling is reached and the U.S. Treasury’s so-called “extraordinary measures” are exhausted. But the truth is, there is enough revenue to pay interest on the debt and avoid a default, and still meet a substantial amount of the obligations of the federal government. It’s up to Biden. He can deal now, or deal with the fallout later.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.