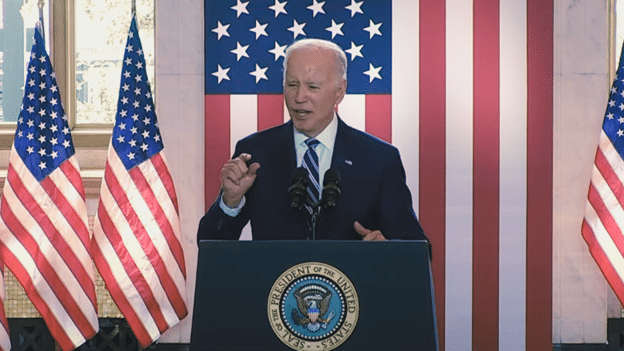

President Joe Biden wants to run on the strength of the U.S. economy, in a June 28 campaign speech in Chicago Illinois, touting the U.S. as the “strongest economy in the world”. He might not have much choice — presidents are judged by the health of the economy in many respects when they stand for reelection — but he might also want to be careful what he wishes for.

The recovery from the Covid recession may already be about to be in the rear view mirror, according to government economic projections.

Peak employment is what we have right now, with unemployment currently at 3.7 percent in May, up from 3.5 percent in April and the Federal Reserve projecting it to rise to 4.1 percent this year and up to 4.5 percent in 2024, an implied 1.3 million jobs losses as it sees inflation continuing to cool.

And so Biden will continue to focus on the relatively low unemployment rate, while he still can, because there might not be much else to talk about later. As inflation cools from its June 2022 peak of 9.1 percent, it’s down to an elevated 4 percent over the past 12 months as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, historically, that has correlated with upticks in the unemployment rate.

In Jan. 2021, average weekly earnings were growing at 7.36 percent annualized, dropping to 4.55 percent in June 2021 as millions more reentered the labor force and staying down there at 4.8 percent by June 2022. That corresponded with inflation that has remained higher that incomes: 1.4 percent annualized in Jan. 2021 when Biden took office to 5.4 percent by June 2021, to 7.5 percent by Jan. 2022 right before Russia invaded Ukraine and peaking at 9.1 percent in June 2022. Even now, as annualized inflation has slowed down to 4 percent currently, so too have wages, to 3.3 percent growth over the past twelve months.

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) measured by the Bureau of Economic Analysis slowed down to 2 percent annualized growth in the first quarter of 2023, from 3 percent in the third quarter of 2022 and 2.6 percent in the fourth quarter of 2022. The Fed is projecting on a median basis that it will be 1 percent overall in 2023 for the year and just 1.1 percent in 2024.

That agrees with the labor market outlook as peak employment never lasts forever. It’s a condition reached when the economy can no longer expand production. When coupled with relatively high inflation, ultimately what happens is households tap out their budgets, spending is curtailed, business revenue slows and then the layoffs ensue.

Holding it back are the current labor shortages, with job openings measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics at 10.1 million, quite high and yet more than 15.9 percent below the 12 million peak in March 2022. Fueling the labor shortages are the number of Americans retiring increasing dramatically. Americans not in the labor force 65 years old and older has increased 3.27 million since Feb. 2020, from 28.3 million to 31.4 million today. In Jan. 2009 it was just 20.1 million.

In a normal business cycle, without the retirement wave and labor shortages, one might expect labor market upheaval in a subsequent recession to be relatively worse than what the Fed currently sees ahead.

It is a situation comparable to that of Japan’s demographic decline with a rapidly aging population that followed low fertility rates — babies per woman there were down to 1.3 in 2021 — that fuels the overall labor shortage and dwindling tax base. During the financial crisis and Great Recession of 2008 and 2009, the unemployment rate only reached 5.7 percent (here it reached 10 percent in Oct. 2009), and just 3.2 percent during the Covid recession.

The U.S. is not much better off demographically, with 1.66 babies per woman in 2021, a situation that longer term will mean a relatively smaller labor force. If it leads to less production overall, and more supply chain shortages, that could mean higher inflation. If that inflation overheats the economy as households max out their credit cards, then that could indeed mean recessions, albeit tempered by the labor shortage.

Here, Biden is hoping to thread the needle or at least forestall any downturn until after the 2024, as long as the economy will cooperate. One metric to watch there is the spread between 10-year and 2-year treasuries, which has been inverted since July 2022. Usually before recessions, such an inversion will occur, but the upheaval in labor markets is not always seen until it “uninverts” as longer-term interest rates collapse in the recession and investors flock to treasuries.

In the meantime, Biden is doing what any president would do facing reelection, emphasizing the historically low unemployment rate and any other shred of good news while he still can. But nothing lasts forever, Mr. President, and time may already be running out. Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.