The Federal Reserve on Sept. 20 held the federal funds rate steady at 5.25 percent to 5.5 percent amid inflation jumping in August to 3.7 percent annualized from 3.2 percent in July, stating that “[i]n determining the extent of additional policy firming that may be appropriate to return inflation to 2 percent over time, the Committee will take into account the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments. In addition, the Committee will continue reducing its holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities, as described in its previously announced plans.”

By continuing to dump U.S. treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, thereby increasing the supply of bonds, prices fall, and while also increasing the federal funds rate — it was at near-zero percent in Jan. 2022 — means consumer interest rates will continue to rise, owing to the inverse relationship between interest rates and the value of bonds.

As a result of the Fed’s overall tightening, 10-year treasuries have risen from 1.7 percent in Jan. 2022 to 4.37 percent today, and 30-year mortgage bonds have similarly increased from 3.2 percent in Jan. 2022 to 7.18 percent today.

This in turn soaks up additional dollars from the economy after the M2 money supply increased by almost $7 trillion during and after Covid, peaking at $22 trillion in April 2022, 43.5 percent above its $15.35 trillion mark in Feb. 2020 right before Covid shut down the global economy, leading to lockdowns and production halts that exacerbated the global supply chain crisis. Now, amid the tightening, the M2 money supply has decreased $1.3 trillion to $20.7 trillion, a 5.9 percent drop. That’s tighter, but still well above its original start point prior to Covid.

In addition, the Fed is projecting unemployment to continue to rise, averaging 4.1 percent in 2024. With the current unemployment rate at 3.8 percent, this is an implied loss of about 503,000 jobs between now and then. That’s nothing to sneeze at, but it’s also far fewer anticipated job losses than were seen in the two prior mega-recessions of 2008 and 2009, and again in 2020, when millions of jobs were lost.

And a huge chunk of that is because of labor shortages brought about by the continue Baby Boomer retirement wave. Americans not in the labor force 65 years old and older has increased 3.57 million since Feb. 2020, from 28.3 million to 31.7 million today. In Jan. 2009 it was just 20.1 million. As Baby Boomers retire, it creates job openings that appear to offset potential jumps in the unemployment rate as the economy overheats.

As a result, there are 8.8 million job openings currently, compared to just 4.9 million in March 2007. But even that is far lower than its peak of 12 million in March 2022, a 26.6 percent drop, as employers give up on hopes of expansion and/or positions are otherwise filled.

A key question going forward will be whether inflation continues to rise amid increased demand for energy, indicating the economy still has some juice left that could temporarily forestall upheaval in labor markets. On that count, oil has continued its upward march, with light sweet crude reaching more than $90 as of this writing. That’s up from $67 in mid-June.

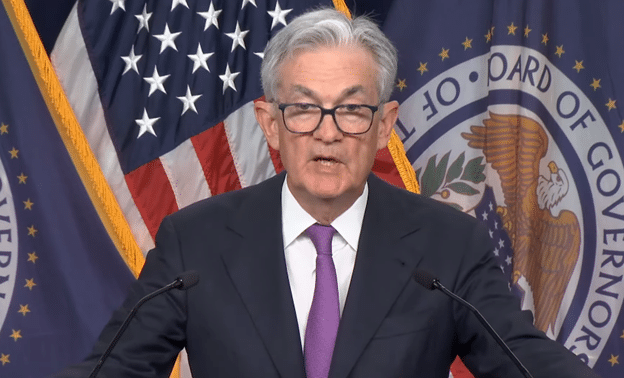

On that front, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell reported in the central bank’s Sept. 20 press conference that the rate hikes might not be done yet: “a majority of participants believe that it is more likely than not that we will that it will be appropriate for us to raise rates one more time in the two remaining meetings this year. Others believe that we have already reached that so it’s … something where … we’re not making a decision … about that question by deciding to just maintain the rate and await further data… [S]o right now it’s still an open question about sufficiently restrictive.”

And that sounds about right. If it’s still time to fight inflation, the Fed can worry about labor market upheavals later and then cut rates at the appropriate time should unemployment significantly rise at a time when inflation is falling. What would make that trickier would be if both unemployment and inflation, which usually share an inverse relationship, were exceptionally high at the same time, as it was in the 1970s and 1980s. As usual, stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.