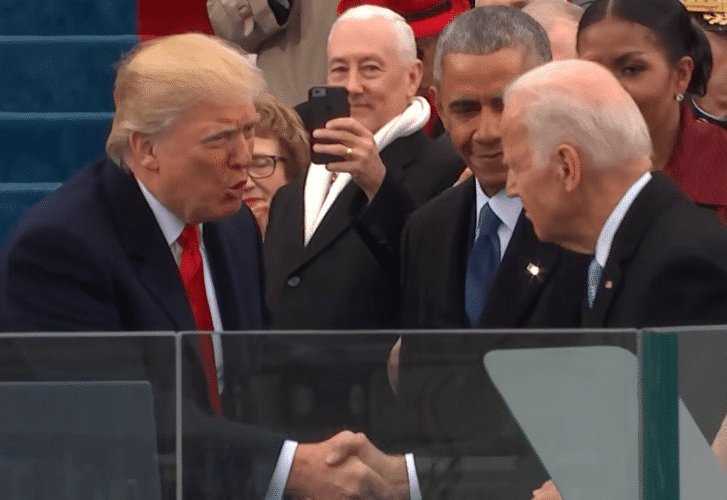

Both consumer and producer inflation accelerated as former President Joe Biden left office in January and President Donald Trump was sworn into office on Jan. 20, to annual rates of 3 percent and 3.5 percent, respectively, according to the latest data compiled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Besides illegal immigration and the border, inflation and the U.S. economy were top issues in the election that almost certainly helped President to oust the incumbent Biden-Harris administration and secure a second term of office as American households watched the cost of living far outpace the growth of incomes.

Inflation is a cruel tax and, politically, it is non-partisan, with spikes in consumer prices and corresponding recessions in the past preceding the ouster of Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush, all one-term presidents, who although each had policies that addressed the economy, could never overcome public discontent over the state of affairs.

And so it was with Biden and the Democrats’ nominee in 2024, former Vice President Kamala Harris. No matter if the Democratic-controlled Congress in 2021 and 2022 passed bills like the so-called Inflation Reduction Act, or all of the assurances how prices were “coming down” when merely the pace of increases had slowed down and prices had not decreased at all, no amount of happy talk was enough to save Biden, who was deposed by his own party, and later Harris, who inherited all of the advantages — and disadvantages, as it turned out — of being the incumbent even as she failingly attempted to rebrand herself as a “new face”.

In 1981, Ronald Reagan inherited a very similar problem. The 1980 recession was particularly bad with inflation hitting 13.5 percent and unemployment hitting 7.2 percent, and so Jimmy Carter lost in a landslide to Reagan. But it turned out, the economic turbulence was not through yet, with inflation still at 10.1 percent in 1981 and unemployment rising to 7.6 percent, and in 1982 recession hit and while inflation slowed to 6.15 percent, unemployment rose to 9.7 percent. This hurt somewhat politically as Republicans lost 26 seats in the House but were still able to retain the Senate with no seats lost.

To kill the inflation, in 1981, Reagan and Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker took the Federal Funds Rate all the way up to 16.4 percent and then kept it above that of the consumer inflation rate, which by 1983 had gone all the way down to 3.1 percent, but unemployment was still high coming out of the recession, at 9.6 percent. Fortunately for Reagan, he and the economy took its medicine and in 1984, unemployment dropped to 7.5 percent, and although inflation ticked up slightly to 4.36 percent, Reagan was still easily reelected. Killing the inflation was the most important thing.

The key consideration: It was really, really hard. Coming into office, the U.S. had just come out of one recession, and it would take aggressive policies to strengthen the dollar and raise interest rates — usually not great for economic growth and labor markets — that broke inflation’s back. Reagan coupled it with tax relief in order to create future circumstances that once the bottom was hit, the U.S. economy would take off like a rocket ship, which it did, amid technological innovations and a relaxed regulatory environment.

Now, Trump wants to emulate Reagan in part, as he did in his first term, by cutting taxes and regulations again and boosting production, but also to cut spending, something Reagan failed to achieve as the national debt has climbed an average of more than 8 percent since 1980.

Optimistically, with the assistance of the U.S. Treasury, the White House Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) and Republican majorities in the House and Senate, Trump and DOGE head Elon Musk believe that the deficit can be cut in half, and Trump hopes to make up the rest by boosting revenue with tariffs from goods abroad and onshoring production, boosting the economy overall, which always increases revenues and hopefully lowering prices.

Inflation, after all, is too much money chasing too few goods, so to lower prices or just merely slow down the growth of prices to a rate lower than the rate of increase of incomes–boosting purchasing power—the two things to do is to reduce the money supply and to increase domestic production energy, food and everything else to boost supplies.

On reducing the money supply, there are of course spending cuts, which will reduce the need to borrow money and monetize the debt by printing more money, but there are also interest rates and then perhaps the biggest one, the ability to strengthen the U.S. dollar. When the dollar is really strong, inflation can be all but eliminated, but it is important to remember that too much of something is not good either. In the 1930s when the dollar was too strong, it led to deflation, mass unemployment and the Great Depression.

Given the menu of options, it might feel a little bit like choosing your poison. But really it’s just picking your battles. In 2021, Biden chose inflation in order to prioritize lowering unemployment following Covid by continuing to artificially boost demand with more deficit spending, but too much of something wasn’t good, and by June 2022 inflation had peaked at 9.1 percent. By then, the Fed was hiking interest rates, the dollar strengthened and inflation began to slow down, but not before Democrats lost the House in 2022 and the White House and the Senate in 2024.

Unfortunately, there is a rather inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment that is very easy to identify in the charts. Want to lower unemployment? Sure, that can be done, just print more money, but expect inflation to rise as it did in 2021 and 2022. Want less inflation? Sure, there’s a way to do that by strengthening the dollar, but expect unemployment to rise, as it did in 2023 and 2024.

Sometimes, we have to teach our children, first this, then that. Biden tried to have his cake and eat it, too, imagining that he could lower unemployment, print trillions of dollars after Covid, stamp down energy and agriculture production without too much inflation, and when that turned out not to be true, to hike interest rates and strengthen the dollar without increasing unemployment and still get reelected, which also turned out not to be true. It was all a fantasy. Biden and Congress spent too much money and the Fed waited too long to hike rates and strengthen the dollar after the inflation accelerated, still operation on zero-bound rates as inflation hit 7.5 percent in Jan. 2022 before Russia invaded Ukraine.

But that is all hindsight. What matters is the here and now, and what to do next. If the top priority is to keep inflation down, Trump, who understands the tradeoffs between supply and demand, will also have to appreciate the economic tradeoffs between the economy running hot, which increases prices, and cool, which lowers prices. Yes, boost production, cut regulations, cut taxes, cut spending, and remember, if all else fails, the dollar is a powerful weapon as well — just don’t be afraid to use it with care.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.