At his recent address to a joint session of Congress on March 4, President Donald Trump noted that upon taking office he had “imposed an immediate freeze… on all foreign aid” via a January 20 executive order.

Under the Jan. 20 Trump executive order, departments and agencies were to stop all “new obligations and disbursements”: “All department and agency heads with responsibility for United States foreign development assistance programs shall immediately pause new obligations and disbursements of development assistance funds to foreign countries and implementing non-governmental organizations, international organizations, and contractors pending reviews of such programs for programmatic efficiency and consistency with United States foreign policy, to be conducted within 90 days of this order.”

Under Article II of the Constitution, Presidents set American foreign policy, whether in negotiating new treaties or in terminating old ones— see George Washington’s 1793 Proclamation of Neutrality that ended the U.S. military treaty with France, George W. Bush’s withdrawal from the 1972 the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty and Trump’s withdrawal from the 1987 Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty, among others.

In terminating the ABM Treaty, the Justice Department Office of Legal Counsel offered this opinion in 2001: “Presidential authority over treaties stems from the President’s leading textual and structural position in foreign affairs generally, from the text and structure of Article II’s vesting of all of the federal executive power in the President, and from the specific manner in which the Constitution allocates the treaty power. Construing the Constitution in this manner comports with the President’s Article II responsibilities to conduct the foreign affairs of the nation, to act as its sole representative in international relations, and to exercise the powers of Chief Executive. Historical practice also plays an important role in resolving separation of powers questions relating to foreign affairs. Judicial decisions in the area are rare, while the need for discretion and speed of action favor deference to the arrangements of the political branches. The historical evidence supports the claim that the President has broad constitutional powers with respect to treaties, including the powers to terminate and suspend them.”

If the President can terminate treaties — which required two-thirds of the Senate to approve — including those that established military alliances, as an inherent exercise of Article II executive power, how can he not stop foreign aid to countries who might no longer be considered allies by the President?

That’s a good question, but not yet one that has been taken up by U.S. District Judge Ali Amir for the District of Columbia, who on Feb. 13 ruled that the payments had to resume.

U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts on Feb. 26 had temporarily reinstituted President Donald Trump’s Jan. 20 freeze of foreign aid pending a hearing of the case by the Supreme Court, lifting a U.S. District Court order that the payments continue in spite of Trump’s freeze.

Then, the Supreme Court backed away from the case on March 5, issuing a decision that lifted the Supreme Court’s stay on the Judge Amir’s ruling. The narrow ruling merely stated, “Given that the deadline in the challenged order has now passed, and in light of the ongoing preliminary injunction proceedings, the District Court should clarify what obligations the Government must fulfill to ensure compliance with the temporary restraining order, with due regard for the feasibility of any compliance timelines.”

Thus greenlighting Judge Amir to proceed with the case, on March 10, he appears to be on the verge of expanding his decision to include a brand new requirement, first of its kind in the history of the republic, that all appropriations made by Congress have to be spent, stating, “The provision and administration of foreign aid has been a joint enterprise between our two political branches. That partnership is built not out of convenience, but of constitutional necessity… Congress, exercising its exclusive Article I power of the purse, appropriates funds to be spent toward specific foreign policy aims. The President, exercising a more general Article II power, decides how to spend those funds in faithful execution of the law. And so foreign aid has proceeded over the years.”

The ruling provides that any services rendered must be paid: “The Restrained Defendants shall not withhold payments or letter of credit drawdowns for work completed prior to February 13, 2025.”

And all monies must be made “available for obligation” under the ruling: “The Restrained Defendants are enjoined from unlawfully impounding congressionally appropriated foreign aid funds and shall make available for obligation the full amount of funds that Congress appropriated for foreign assistance programs in the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2024.”

A separate injunction by U.S. District Judge for the District of Columbia Loren Alikhan on Jan. 28 against a now-rescinded memorandum by the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) that would freeze all federal contracts had only sought to limit the injunction to “all open awards,” but that “not affect OMB’s memorandum as it pertains to ‘issuance of new awards’ or ‘other relevant agency actions that may be implicated by the executive orders.’”

So, now Amir appears to want to go much further, saying that if Congress appropriates money for a purpose, it must be spent. Or did he? Amir appeared to balk at the edge of such a ruling, stating, “The Court accordingly denies Plaintiffs’ proposed relief that would unnecessarily entangle the Court in supervision of discrete or ongoing Executive decisions, as well as relief that goes beyond what their claims allow… The separation of powers dictates only that the Executive follow Congress’s decision to spend funds, and both the Constitution and Congress’s laws have traditionally afforded the Executive discretion on how to spend within the constraints set by Congress.”

Therefore, Amir concluded, “The appropriate remedy is accordingly to order Defendants to ‘make available for obligation the full amount of funds Congress appropriated’ under the relevant laws.”

There’s just one problem. The funds are already available for obligation under the appropriations since enacted. They’re just not being obligated.

But that’s nothing new. Every single year, Congress appropriates monies that do not get fully spent.

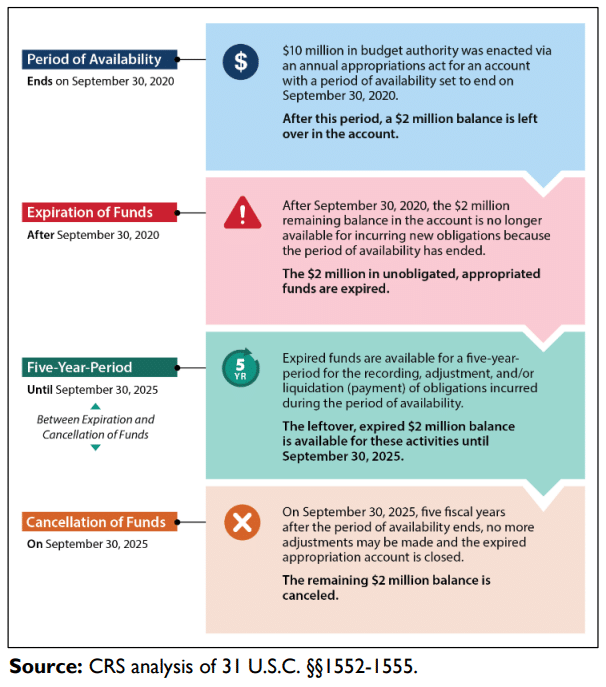

Sometimes Congress provides a one-year window for funds, and other times a multi-year window. According to a Feb. 2024 report by the Congressional Research Service , “In most cases, appropriated funds may be obligated only during a defined period of availability. One-year funds are appropriations that remain available for obligation for one year. Multiyear funds are appropriations that remain available for obligation for more than one year.”

Congress has even provided for a procedure for automatically canceling unobligated funds in 31 U.S. Code Sec. 1552(a) after a five-year period if they have not been repurposed: “On September 30th of the 5th fiscal year after the period of availability for obligation of a fixed appropriation account ends, the account shall be closed and any remaining balance (whether obligated or unobligated) in the account shall be canceled and thereafter shall not be available for obligation or expenditure for any purpose.”

But departments and agencies under the law are under no obligation to spend the money. In fact, under 31 U.S. Code Sec. 1553, under subsection (a), it states if the monies are unspent, they will remain available for reappropriation, “After the end of the period of availability for obligation of a fixed appropriation account and before the closing of that account under section 1552(a) of this title, the account shall retain its fiscal-year identity and remain available for recording, adjusting, and liquidating obligations properly chargeable to that account.” For an amount above $4 million to be spent on something else can only be done at the discretion of the head of the agency and for amounts about $25 million then the agency head must submit a notice to the House and Senate Appropriations Committees, with a 30-day window.

So, what might happen? For contracts already let by the federal government under former President Joe Biden’s tenure, it might be that federal courts continue to say that those contracts must be executed. But for new contracts, there does not appear to be a means — short of Congress not delegating so much spending discretion to the executive — to compel Trump to spend the money. Under the law, if they are not obligated, they will become unobligated, and then after a period of time returned to the Treasury.

Instead, the President might decide it is better to hold back certain funds as a means of negotiating with foreign governments, as he recently did with Ukraine, temporarily withholding military and intelligence aid in order to compel Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to the peace table.

Again, if the President — not just President Trump, but any president — can withdraw from a treaty, then he can withhold foreign aid to achieve a foreign policy objective.

But if this keeps up, where courts try to spend the money on behalf of the executive branch, Congress might consider just suspending the Impoundment Control Act (certainly an option), or perhaps Trump could just tell the State Department to use any unused foreign aid dollars for another type of distribution to foreign actors — start paying off the $8.5 trillion of treasuries owed to foreign creditors. Just pay down the debt. There, it got spent on foreign actors. Happy?

Robert Romano is the Executive Director of Americans for Limited Government Foundation.