“[S]uccessive interventions by the Fed during and after the financial crisis created what amounted to a de facto backstop for asset owners. This led to a harmful cycle whereby asset owners came to control an ever-larger portion of national wealth. And within the class of asset owners, the Fed effectively chose winners and losers by expanding asset purchase programs beyond Treasuries to private obligations, with the housing sector receiving particularly favorable treatment.”

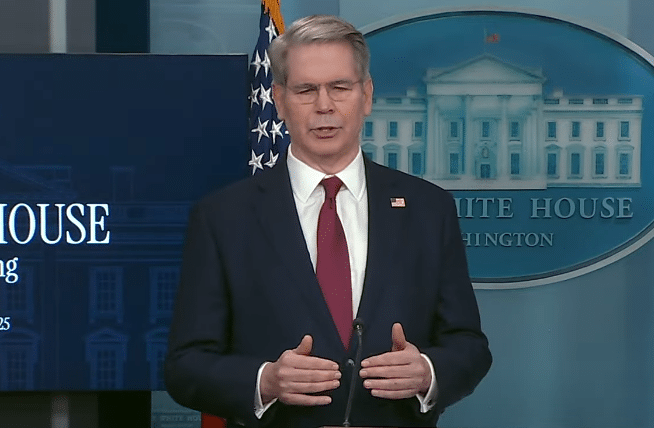

That was Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent in a lengthy column in The International Economy blasting the Federal Reserve’s increased bent to interventionism, particularly in housing markets, following the financial crisis of 2007 to 2009, under the chairmanship of Ben Bernanke, who brought the federal funds rate to 0 percent for the years that followed, and dramatically expanded the Fed’s balance sheet by trillions including what eventually became $1.77 trillion of net purchases mortgage-backed securities by December 2017.

These purchases were to take negative equity mortgages off of the balance sheets of banks, gifting 100 percent of the bonds’ market value back to the banks who bought the bonds based on the overinflated prices. By December 2008, prices in the Freddie Mac Home Price Index were collapsing 12.3 percent year over year. The intervention followed the wave of millions of foreclosures as homeowners trapped in negative equity traps — they could not afford to sell as sales resulted in money owed to the bank — instead opted to walk away from their homes.

A year later, by December 2009, the Fed had bought about $900 billion of mortgage-backed securities. The prices were still collapsing but the deflation had slowed to prices dropping 3 percent. In 2010, it bought another $100 billion as Congress extended a homebuyer’s tax credit, an deflation expanded in 2010 as priced dropping 4.8 percent. With prices hitting bottoms in 2011 — deflation slowed to 2.7 percent that year — the Fed switched to selling about $50 billion of mortgage securities. In 2012, it added another $100 billion, to about $950 billion, as markets finally recovering and home prices finally increasing 6 percent.

And then, in 2013, to finish it off, Bernanke went big, bought another $500 billion as home values exploded 10 percent. Again, by the end of 2017, following the reign Janet Yellen, the total went from $1.5 trillion to $1.7 trillion. From 2014 through 2017, home prices grew between 6 and 7 percent a year.

Then in 2018, under Jerome Powell, the Fed began selling again, taking mortgage securities down to 1.4 trillion by December 2019, by which time home inflation had slowed to 4.3 percent.

Housing was becoming more affordable relative to incomes but suddenly Covid struck and the Fed resumed buying amid the global lockdowns. By March 2022, the Fed’s balance sheet for mortgage securities had exploded to $2.7 trillion—with price increases not seen since the housing bubble—that month year over year prices were increasing 18.5 percent.

Hit with crippling inflation, the Fed began selling again—it currently owns $2.1 trillion of mortgage securities—and then prices slowed to 1 percent a year later and then 6 percent by December 2023. In December 2024, it slowed to 4.2 percent. The latest reading in July 2025 had prices only growing 1.4 percent as demand has cooled considerably.

Simply put, thanks to the Fed, housing has become unaffordable. Whereas in 2008 there was definitely a negative equity squeeze on housing markets, in 2020 during Covid, there were no such adverse market conditions but the Fed bought mortgages anyway — about $600 billion worth in 2020 alone — because that’s what it had done the last time the economy collapsed. Buying mortgages was simply out of an abundance of caution as the economy faced the unknown. That year, by December 2020, home values had increased 11.4 percent.

These outcomes favored those who already owned homes, per Bessent’s analysis, as the Fed’s actions have driven prices: “The Fed’s actions along the risk and time curves compressed interest rates, driving up the prices of assets. This mechanism disproportionately benefited those who already owned assets. Homeowners, for example, saw the value of their properties soar. They were mostly shielded from the effects of rising interest rates given the structure of the U.S. housing market, where over 90 percent of all mortgages are fixed-rate. As a result, the housing market remained overheated even as interest rates rose, with over 70 percent of existing mortgages carrying rates more than three percentage points below the prevailing market rate. At the same time, less well-off households, shut out of homeownership by rising interest rates, missed out on the asset appreciation that benefited wealthier households. These households also faced tighter financial conditions as higher interest rates drove up the cost of borrowing. Meanwhile, inflation—partially fueled by the Fed’s massive expansion of the monetary base through QE and the associated accommodation of record fiscal spending— disproportionately affected lower-income Americans, further exacerbating economic inequality. And it put homeownership out of reach for a generation of young Americans. By failing to deliver on its inflation mandate, the Fed allowed class and generational disparities to worsen.”

Secretary Bessent is right. Just look at the times when the Fed was buying and selling. Since the financial crisis, when it as buying mortgage securities, home values increased, and when it has been selling, home valuations have slowed. And it’s been doing that for almost 20 years now. Bernanke had a plan for getting in, but did he have a plan for getting out?

So, what is to be done? Far less, per Bessent: “Looking ahead, it is essential the Fed commit to scaling back its distortionary impact on markets. At a minimum, this likely includes the Fed only using, and then halting, unconventional policies like QE in true emergencies and in coordination with the rest of government… We now face not only short- and medium term economic challenges but also the potentially dire long-term consequences of a central bank that has placed its own independence in jeopardy.” This is a timely warning.

Home prices historically have sagged in recessions, and the current slowdown comes in a period of slow but steadily rising unemployment. Hopefully we’re almost through that part but it’s the hangover after the Covid binge. We need a healthier monetary policy.

Robert Romano is the Executive Director at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.