“So, together, we had 12 months of unprecedented success in 2025 and now we’re going to make history and break records with the epic midterm victory that we’re going to pull off. It just doesn’t seem to happen for people that win the presidency. It’s an amazing phenomena. You know, you win the presidency, and we sure as hell are having a successful presidency. I will say that. But even if it’s a successful presidency, and it’s been nothing like what we’re doing. We had a very good day two days ago, too. But even if it’s successful, they don’t win. I don’t know what it is. There’s something psychological like you vote against. You can win by a lot. We won every swing state. We won the popular vote by millions. We won everything. But they say that when you win the presidency, you lose the midterm.”

That was President Donald Trump on Jan. 6 speaking at the House Republican Member Retreat to discuss strategy for the 2026 Congressional midterms, outlining his goal for Republicans to do well and keep their House and Senate majorities, while acknowledging the grim reality facing the incumbent party seemingly regardless of the circumstances. He’s right.

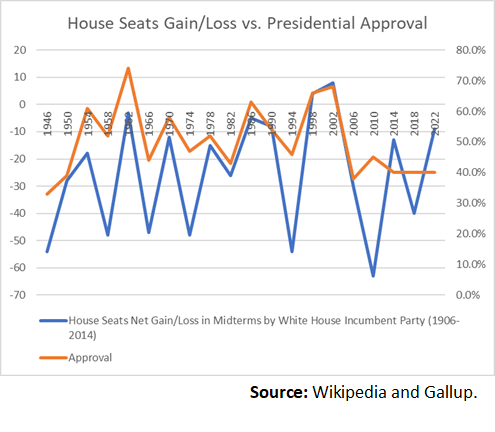

In fact, in midterm elections dating back to 1906 through 2022, the party that occupied the White House lost seats in the House 27 out of 30 times, or 90 percent of the time, and in years with losses those averaged 34 seats. It was only overcome in 1934, 1998 and 2002, with the Great Depression, Monica Lewinsky and the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks acting as exigent events.

Another edge case is 1962, wherein Democrats only lost three seats, and came within weeks of the Cuban Missile Crisis being resolved.

In 2018, Republicans lost 41 House seats. The Senate is a little better, with losses only occurring 66 percent of the time, with losses averaging 6 seats. In 2018, Trump and the GOP picked up two Senate seats.

So, what about these exceptions to the rule? Nothing mysterious. Quite simply, the one thing the President’s party had going for it in 1934, 1962, 1998 and 2002 were all very high presidential approval around Election Day.

Going back to 2002 and 1998 and both George W. Bush and Bill Clinton had pretty high approval ratings, 68 percent and 66 percent, respectively, and were able to beat the midterm jinx by picking up seats in the House, 8 seats and 5 seats, respectively.

Similarly, in 1962 John Kennedy also had a high approval rating, measuring 74 percent post-election and post-crisis, only losing 3 seats, the lowest losses in a year when there were losses.

The only other exception was 1934 — but Gallup doesn’t get started until 1941 in World War II and even then Franklin Roosevelt had sky-high approval as you’d imagine — and I think we can surmise it was high in 1934, too.

Now, Roosevelt also had very high approval in the 1942 midterms but still lost seats as he had in the 1938 midterms, 45 House seats and 72 House seats, respectively, owing to Republicans regaining the many of the lopsided gains Democrats had achieved during the early years of the Great Depression, when Republicans were wiped out almost to the point of political extinction. Those are examples where the map and what districts were up mattered a lot.

There are also examples of presidents with high approval. In 1954, Dwight Eisenhower had a 61 percent approval rating around Election Day, and so only lost 18 seats in the House. Similarly, in 1970, Richard Nixon had a 58 percent approval rating and only lost 12 seats. These are both below the 34-seat loss average. And in 1986, Ronald Reagan had a 63 percent approval rating and only lost 4 House seats, but this was overshadowed by losing 8 seats in the Senate as the Iran-Contra scandal was breaking.

And lower approval also shows greater losses in the dataset. In 1946, Harry Truman was registering just 33 percent approval as Democrats lost 54 House seats. In 1966, Lyndon Johnson had 44 percent approval and lost 47 House seats. In 1974, Gerald Ford only had 47 percent approval and Republicans lost 48 House seats amid the fallout from Watergate. In 1994, Bill Clinton had 46 percent approval and Democrats lost 54 House Seats. In 2006, George W. Bush had 38 percent approval and Republicans lost 30 House seats. In 2010, Barack Obama had a 45 percent approval rating, and Democrats lost 63 House Seats, and in 2014, he had a 40 percent approval rating and lost another 13 seats. And in 2018, Donald Trump had a 40 percent approval rating and Republicans lost 42 House seats.

Another slight exception occurred in 2022, when Joe Biden had a 40 percent approval rating but Democrats only lost 9 seats, with the outlier being largely owed to higher-than-expected Democratic Party turnout after the Roe v. Wade decision barring states from banning abortions was overturned by the Supreme Court.

So, approval matters, exigent events matter — 1934 had the Great Depression, 1962 had the Cuban Missile Crisis, 1998 had Monica Lewinsky, 2002 had 9/11 and war and 2022 saw Roe v. Wade fall — and the map matters to a certain extent.

The Senate, again, is a separate matter as only one-third of the Senate comes up for election every two years by constitutional design. There, the map matters a lot more in terms of which seats are up. Both Trump and Biden managed to pick up Senate seats in 2018 and 2022, 2 seats and 1 seat, respectively.

But what emerges generally is a “check engine” light for presidents in midterm cycles, and that’s to watch the approval rating. Now, a lot can go into presidential approval — an improving economy, a war and so forth.

If you want to beat the midterm jinx, you need high approval. The current president doesn’t have high approval at the moment. Even though President Trump is term-limited, the President’s advisers need to encourage the administration to be doing and saying things that help improve the President’s standing with the American people. Distracting gaffes cannot be afforded. Do stuff that makes people happy.

Right now, President Trump is averaging about 43 percent in the national average of polls. He’s at 36 percent in Gallup. With the exception of 2022, that level of approval lines up with double-digit losses in the House. Yes, the new Congressional maps being drawn in Texas and elsewhere might help on a one-time basis to mitigate such losses on a net basis, so there are indeed certain exigent circumstances coming into play. But so far, it’s shaping up to look like a garden variety midterm election for President Trump and Republicans, which isn’t great news for the incumbent party.

Robert Romano is the Executive Director of Americans for Limited Government Foundation.

Correction: Updated dataset to input the correct gain/losses for 1986, 1998, 2010 and 2018.