“We are at war against drug trafficking organizations and not at war against Venezuela.”

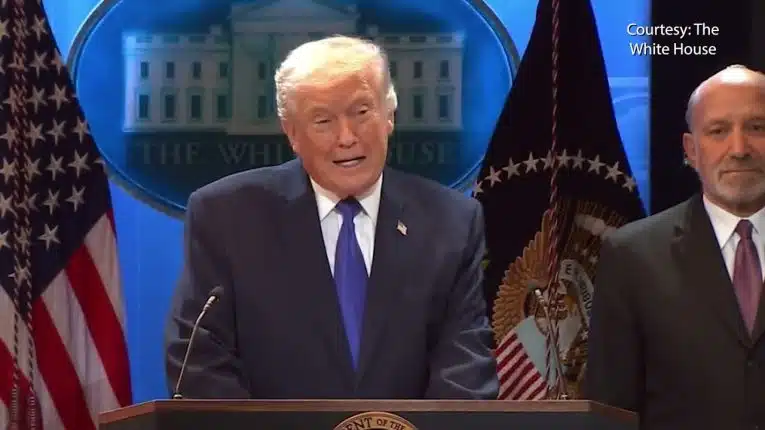

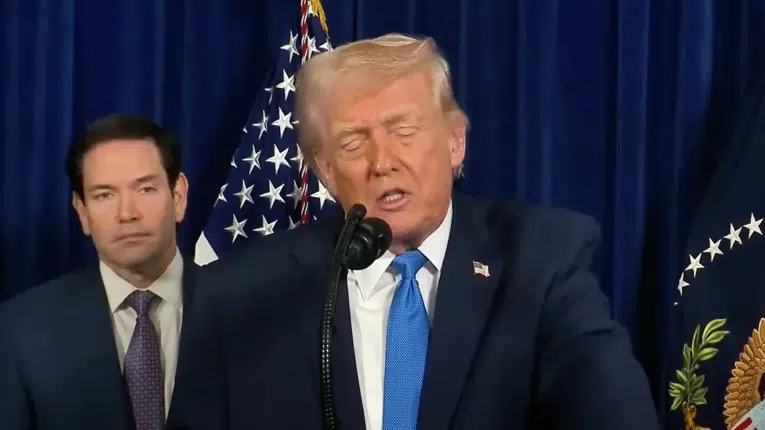

That was Secretary of State Marco Rubio on NBC’s Meet the Press on Jan. 4 conveying President Donald Trump’s policy, that, as of now, there is no state of war that exists between the U.S. and Venezuela.

On Jan. 3, President Trump ordered U.S. armed forces and the Justice Department to capture narco-terrorist Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and his wife for trafficking drugs into the U.S. including cocaine and other deadly poisons, killing thousands of American citizens, and now both face prosecution in the Southern District of New York.

So far, no written notification has been sent by the President to Congress about the operation, as called for in Section 4 of the War Powers Resolution “in any case in which United States Armed Forces are introduced… into hostilities or into situations where imminent involvement in hostilities is clearly indicated by the circumstances… into the territory, airspace or waters of a foreign nation…”

Was it an act of war? The administration says it was a law enforcement operation. Maybe it was both.

The President did send War Powers Resolution notifications in 2025 for U.S. military strikes in Iran to destroy her nuclear facilities in June, for attacking narco-terrorist boats in the Caribbean Sea beginning in September and for strikes in Yemen in March. Trump also used such notifications following military strikes abroad five times in his first administration.

Similarly, in 1989 when George H.W. Bush used U.S. armed forces to capture then Panama dictator Manuel Noriega, he issued the Section 4 notification to Congress.

In this case, however, it’s not a war, the President says — at least, not yet. Or if there was a war, maybe it’s already over. If so, perhaps it should be called the Three-Hour War.

Whether or not there really is a war, though, might actually be up to the new President of Venezuela, Delcy Rodríguez. She has called the capture of Maduro “aggression” but does she want to chance a wider war?

There of course is another way — President Trump’s way, who doesn’t want a war.

Instead, Venezuela can be rebuilt and free elections can once again be held, but the drug trade is over. And that’s okay because the oil trade is back on. I bet they make more money that way, anyway, since selling oil and gasoline is actually legal in the U.S., whereas drug trafficking gets you a one-way ticket to jail.

In any event, Trump is telling Venezuela it must change. No more dead Americans. And no need for armed hostilities.

That’s the apparent deal President Trump is attempting to reach with President Rodriguez.

In so doing, Trump is dusting off the Monroe Doctrine, first articulated by President James Monroe in 1823 to discourage European influence in the Americas, blocking any further colonization of North and South America.

Then, Monroe told Congress in his State of the Union Address: “We… declare that we should consider any attempt on their part to extend their system to any portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety. With the existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered and shall not interfere. But with the Governments who have declared their independence and maintained it… we could not view any interposition… by any European powers in any other light than as a manifestation of any unfriendly disposition toward the United States.”

This was later expanded by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1904, the so-called Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, to include the possibility of the use of military force by the U.S. to protect the Americas, telling Congress: “[I]n the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however, reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power… We would interfere with them only as a last resort and then only if it became evident that their inability or unwillingness to do justice at home and abroad had violated the rights of the United States or had invited foreign aggression to the detriment of the entire body of American nations.” Roosevelt immediately made good on the threat by intervening in the Dominican Republic in 1905, as he had already in Panama in 1903 by establishing a protectorate there, or predating Roosevelt’s tenure, the protectorate over Cuba starting in 1898.

Later, U.S. actions to avert the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 as the Soviet Union put nuclear missiles there or in Nicaragua in 1981 and Grenada in 1983 were other assertions of the Monroe Doctrine and against greater powers who challenged U.S. superiority in the Americas.

Venezuela was said to be a nexus of Chinese and Russian influence in the Western Hemisphere, and Trump said no more.

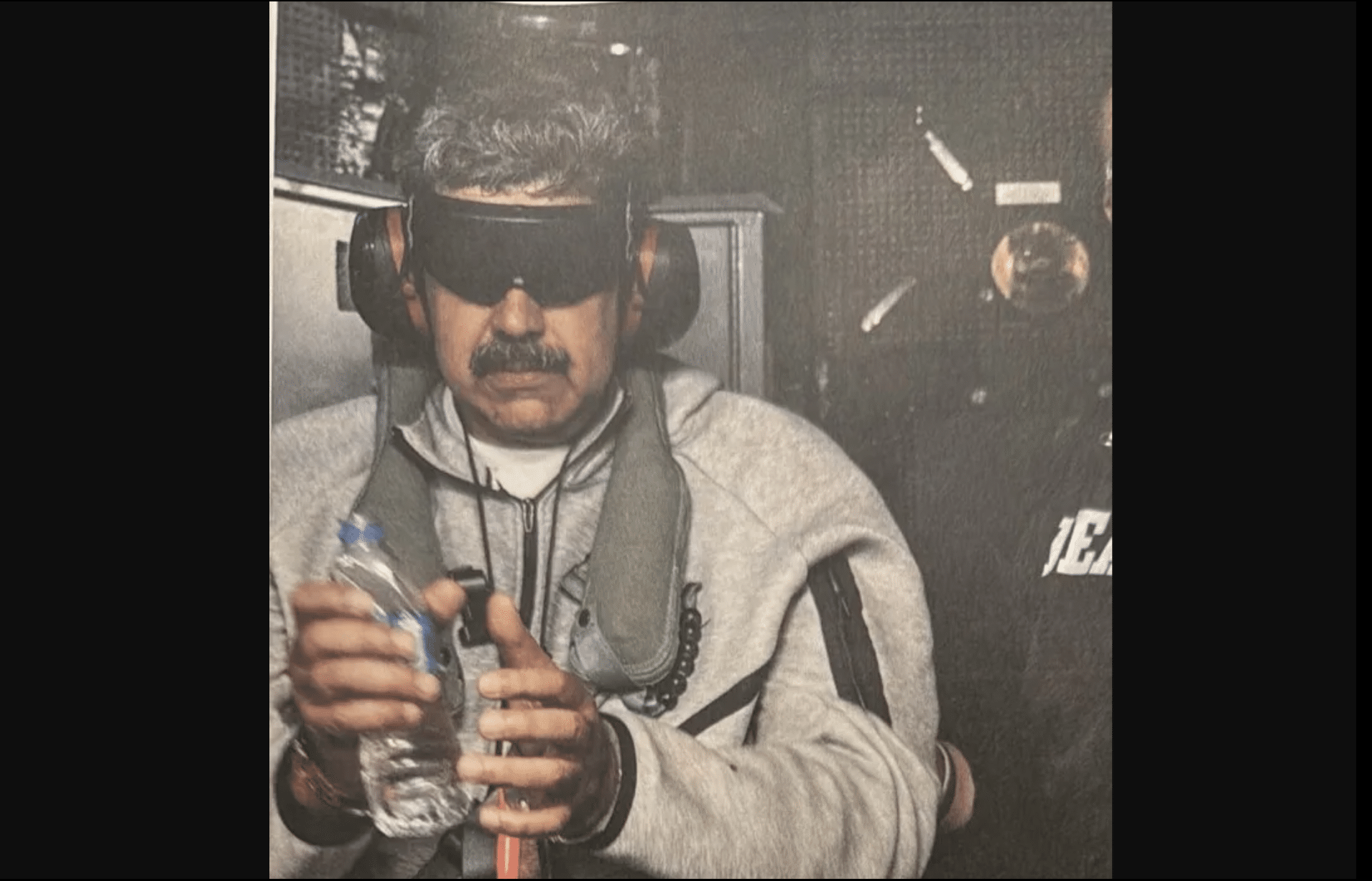

Maduro was offered a well-provided-for exile in Turkey but he said no. That was prior to his own notification that his rule was over delivered by the U.S. armed forces responsible for his capture. Maduro tried it his way, and it didn’t really work out.

As we are fond of saying in the U.S.: No one is above the law. If terrorists and drug traffickers are subject to being captured or killed, then so are drug kingpins, even if they’re presidents.

Now, there may yet be a War Powers Resolution letter sent to Congress under Section 4 subject to Venezuela, but the new president of Venezuela never gets to read it because Rodriguez’ only notification came from a cruise missile. Who knows?

It’s all up in the air. Just the way President Trump likes it. Rodriguez might be better off taking the deal. Better to not find out.

Robert Romano is the Executive Director of Americans for Limited Government Foundation.