The cornerstone of President Donald Trump’s plan to defeat the Chinese coronavirus and save potentially millions of lives, and to salvage what can be of the U.S. economy, is a massive expansion of the Treasury’s Exchange Rate Stabilization Fund from about $93 billion to $500 billion.

These funds will be used to underwrite the economic relief plan, which includes $300 billion for covering payroll for small businesses, $200 billion for critical industries and a gigantic expansion of unemployment benefits that amount to paid sick leave for every American who had a job when the virus struck.

These lending and grant programs are essential to incentivize millions of Americans to stay home to combat the virus, and to help the U.S. economy to survive the effects of being shut down during the outbreak response effort. If done correctly, tens of millions of businesses and hundreds of millions of jobs can be saved.

But the Exchange Stabilization Fund has other important, economy-sustaining uses.

Normally, the U.S. Treasury operates the Exchange Stabilization Fund to “purchase or sell foreign currencies, to hold U.S. foreign exchange and Special Drawing Rights (SDR) assets, and to provide financing to foreign governments. All operations of the ESF require the explicit authorization of the Secretary of the Treasury (‘the Secretary’),” according to Treasury’s website.

Such funds, with enough firepower, could be used to dump dollars on foreign exchange markets to help weaken the dollar in times of financial stress or if foreign trade partners are engaged in competitive devaluation, exacting deflationary pressure on the U.S. economy.

Like now.

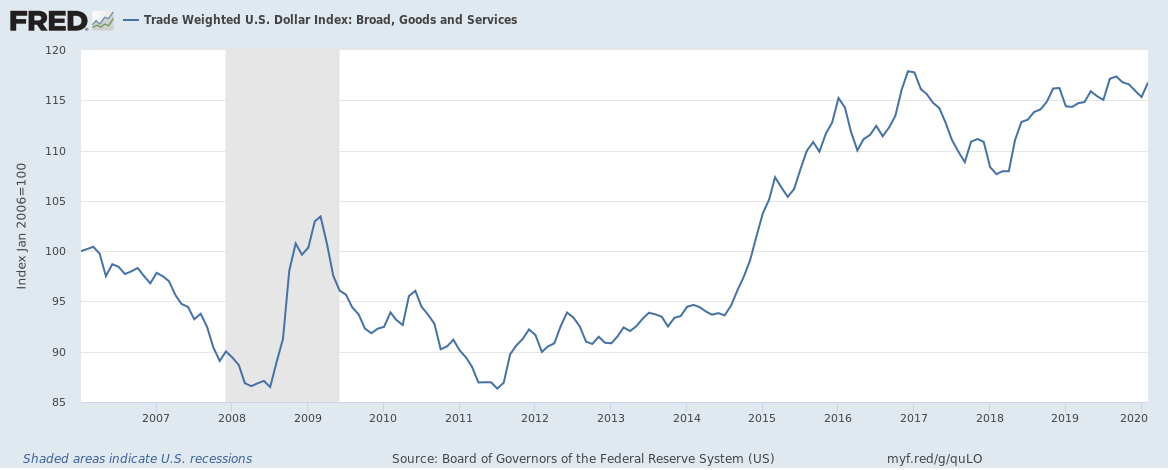

The Trade Weighted U.S. Dollar Index remains near its highest levels in years. The truth is, the coronavirus could not have struck at a worse time. It means the dollar is really strong compared to overseas trading partners and has been for years.

President Trump appears to recognize the problem, but appeared to dismiss the possibility of any intervention on foreign exchange markets, at least for now. On March 23, he said at the White House to reporters, “having a strong dollar is good, but it really sounds good. But the truth is, it makes certain things, like trade, much tougher. And our dollar — I don’t know if you’ve seen, but our dollar has remained very strong, especially against other currencies. Very, very strong. Which, again, makes that trading more difficult, but there’s something nice about having a strong dollar, right? You know, no matter what, I’m President. It’s nice to have a strong dollar. But it does make trading more difficult.”

Right now, however, the dollar is probably far too strong in the wake of the massive recession that just began caused by federal and state governments having practically ordered everything except essential services to be closed.

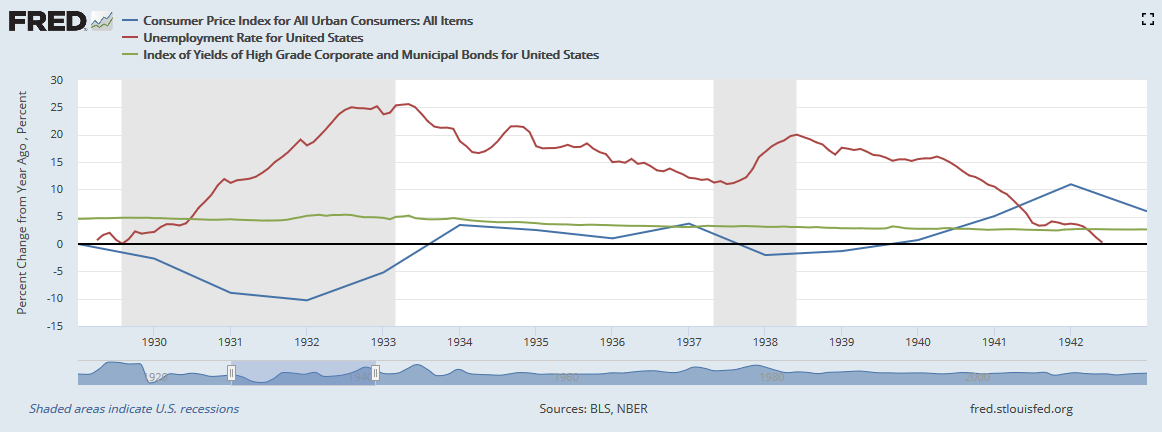

The Great Depression dragged on for years not because of government intervention or tariffs per se, but because of the failure to recognize the adverse impact of keeping the dollar exchange rate to gold so high while the rest of the world was engaged in competitive devaluation and retiring the interwar gold standard.

It was this distortion in monetary policy that caused a recession to turn into a massive depression.

Deflation in the U.S. began after the great inflation of World War I and the ensuing credit expansion, had a brief respite in the 1920s before beginning again in 1927. It then slowed in 1929, and then went crazy starting in 1930 as banks began failing en masse. Inflation was marked at -2.7 percent in 1930, -8.9 percent in 1931, -10.3 percent in 1932 and -5.2 percent in 1933.

As that occurred, unemployment skyrocketed, reaching 11.2 percent by the end of 1930, up to 19.2 percent by the end of 1931, up to 25 percent in 1932 and peaked in March 1933 at 25.4 percent.

It was not until Franklin Roosevelt ended the interwar gold standard in 1933 that some relief was felt as unemployment began collapsing down to 11 percent by 1937 before spiking again in the 1937-38 recession as deflation ensued again. Ultimately, the ongoing problems were not fully alleviated until the massive mobilization of World War II.

A similar trend appeared to play out during the 2000s leading to the financial crisis, when China’s relative low peg to the dollar ultimately coincided with sharp rises in U.S. unemployment and drops in prices, not alleviated until the dollar weakened from 2009 to 2011.

Now, the scourge of deflation could be upon us once again as asset prices plunge after the coronavirus crash. With the global economy essentially frozen while the world waits out the virus, the economy will likely contract massively in first quarter, which ends in a week. Layoffs will be in the millions, and the unemployment rate could be in double digits.

To alleviate the long term impacts over the coming months, the Treasury and Federal Reserve should consider doing precisely what the Exchange Stabilization Fund says, which is to stabilize the exchange rate of the dollar versus trade partners during this national emergency. If there ever was a time for a weaker dollar, it’s right now, Mr. President. We’re going to need all the help we can get.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.