By now, the Georgia state legislature and Gov. Brian Kemp (R-Ga.) have had plenty of time to process to results of the 2020 election, and to make any changes to state election law that might be necessary to ensure that the Jan. 5, 2021 runoff for the Georgia Senate seats currently held by Sen. Kelly Loeffler (R-Ga.) and Sen. David Perdue (R-Ga.) are held freely and fairly.

Democrats need to win both seats with Kamala Harris as the tiebreaker to reclaim the Senate majority in 2021.

No changes to law were made.

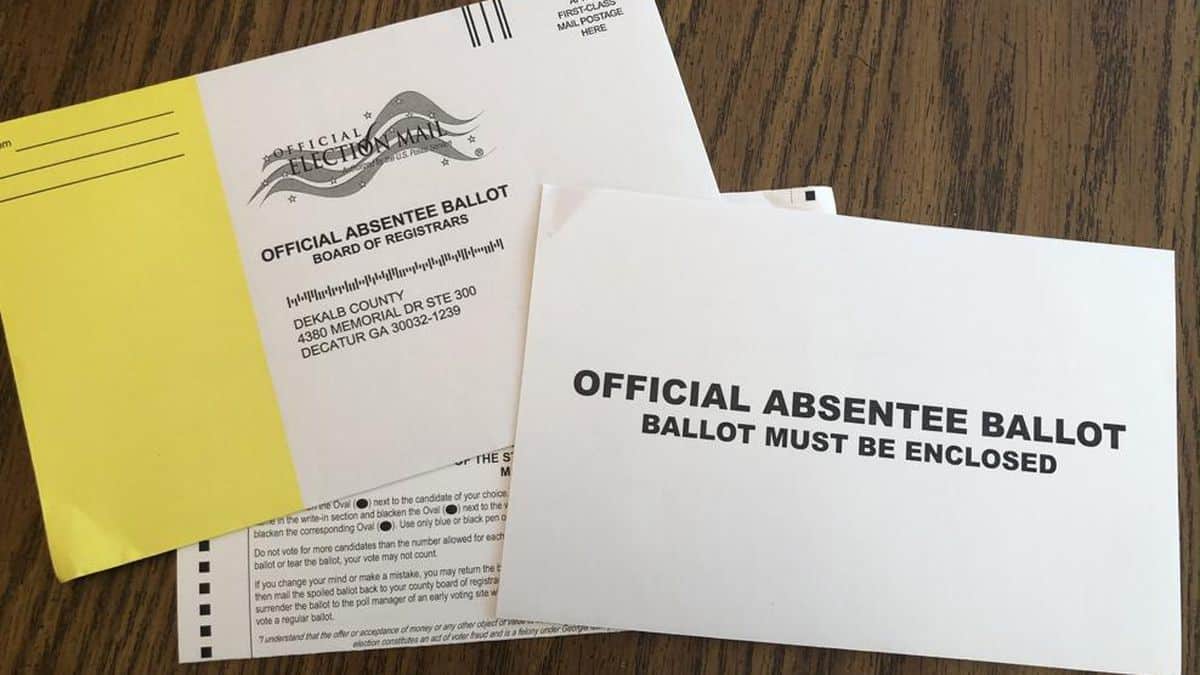

Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R-Ga.) has ordered an audit of signature verification procedures, expected to be completed this week. For all the good it will do. Under state law, a voter’s signature goes on the envelope containing the secret ballot, not the ballot itself. As a result, even if a number of ballots were found to have been ineligible, there would be no way of putting them back in their corresponding envelopes and discounting them.

And don’t expect much to come of the audit, with Raffensperger confidently predicting the audit would restore public confidence in the process, “Now that the signature matching has been attacked again and again with no evidence, I feel we need to take steps to restore confidence in our elections.”

Of course, the objection to the current signature verification process was that the consent decree was out of accords with state law, the terms of which were arbitrarily changed via a March 2020 judicial consent decree with Georgia Democrats — without ever going to the state legislature.

The signature audit is what it is. It will likely affirm that the signature verifications complied with the terms set forth in the March 2020 consent decree.

This consent decree changed the statutory requirement that the signature must match the signature on the voter registration card to simply matching the signature on the absentee ballot application, stating, “County registrars and absentee ballot clerks are required, upon receipt of each mail-in absentee ballot, to compare the signature or mark of the elector on the mail-in absentee ballot envelope with the signatures or marks in eNet and on the application for the mail-in absentee ballot… If the registrar or absentee ballot clerk determines that the voter’s signature on the mail-in absentee ballot envelope does not match any of the voter’s signatures on file in eNet or on the absentee ballot application, the registrar or absentee ballot clerk must seek review from two other registrars, deputy registrars, or absentee ballot clerks.”

State law under Title 21, Chapter 2, Article 10 § 21-2-386 says the signature must match either the voter registration card or the most recent updated registration card and the absentee ballot application, “The registrar or clerk shall then compare the identifying information on the oath with the information on file in his or her office, shall compare the signature or mark on the oath with the signature or mark on the absentee elector’s voter registration card or the most recent update to such absentee elector’s voter registration card and application for absentee ballot or a facsimile of said signature or mark taken from said card or application…”

Arguably, the consent decree effectively amended state law, potentially violating Article I, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution, which states, “The times, places, and manner of holding elections for senators and representatives, shall be prescribed in each state by the legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations…”

If it’s correct, it gets counted, if not, it gets rejected and then voters have up to three days after the election for voters to cure their ballots. Per the state law, “The board of registrars or absentee ballot clerk shall promptly notify the elector of such rejection, a copy of which notification shall be retained in the files of the board of registrars or absentee ballot clerk for at least two years. Such elector shall have until the end of the period for verifying provisional ballots contained in subsection (c) of Code Section 21-2-419 to cure the problem resulting in the rejection of the ballot.”

It is dubious, the idea of resubmitting ballots days after Election Day, far beyond that set forth by Congress under Article I, Section 4 of the Constitution and 2 U.S.C. §7 which states “The Tuesday next after the 1st Monday in November, in every even numbered year, is established as the day for the election, in each of the States.”

Raffensperger has since assured the state and the nation that “When the voter marks their absentee and places it in the envelope to return to the county, the voter MUST sign the oath on the outside of the outer envelope. When the ballot is returned to the county, the first thing the county must do is compare the signature to the absentee ballot application (unless the application was made online) and then also compare the ballot envelope signature to the signature(s) of the voter from the voter registration system.”

Similarly, federal court cases brought on these questions, particularly challenging the consent decree, this past month were summarily dismissed. And the state legislature did nothing to amend the election laws after Nov. 3.

So, these are the rules. And, love them or hate them, those will be the rules followed on Jan. 5 and in the days following.

Between the massive expansion of absentee ballots due to Covid, the outstanding questions on how individual counties verify signatures (do they look at the original registration cards or not?), changes to state law that allow for curing of ballots days after Election Day, and the March 2020 consent decree that upended the signature verifications in the first place, the terrain of the Georgia runoffs is now widely known to both political parties.

Although ballot harvesting is technically illegal under HB 316, the changes to the state’s election laws still boosted turnout considerably in 2020, up 20.6 percent from 4.1 million in 2016 to nearly 5 million, with both Republicans and Democrats increasing their share of votes substantially.

80.2 percent of those, or 4 million, were submitted via absentee ballots.

Republicans boosted their turnout by 17.8 percent compared to 2016, with 75.9 percent of their ballots being absentee in the presidential race, and Democrats boosted their turnout by 31.7 percent, with 84.9 percent being absentee.

That was the difference in the 2020 election, in Georgia and other swing states across the country. And it will be the difference in Georgia on Jan. 5.

So, Republicans are no strangers to absentee voting. They just have to master the new rules, and activate their base to further using the absentee system, including ensuring that their people have the opportunity to cure their ballots too after Jan. 5.

Georgia Republicans need to play by the same rules as Democrats if they want to win.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.