Could Republican state attorneys general now force some of these legal issues back into federal courts, effectively delaying them as happened under Trump in certain cases?

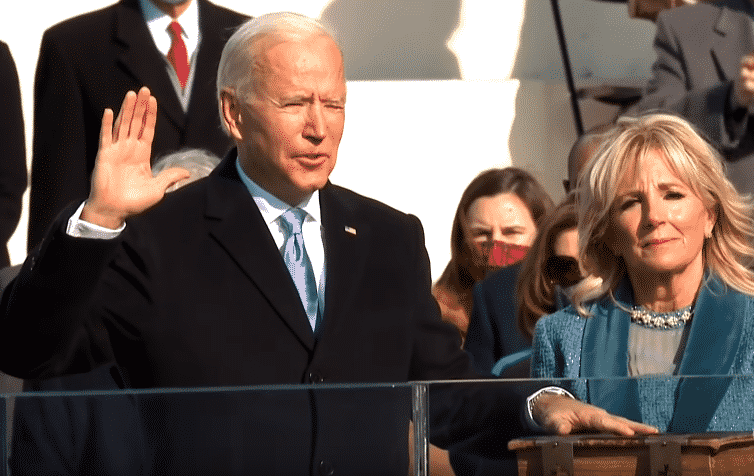

President Joe Biden’s first day in office began with a flurry of executive orders and other actions, taking out former President Donald Trump’s travel restrictions from countries with known Islamist terrorist activity, stopping further construction of the border wall on an emergency basis, rejoining the World Health Organization, reentering the Paris Climate Accords, and halting the Remain in Mexico policy that had asylum seekers wait out their cases in Mexico before being allowed to enter in the U.S.

As these actions occurred in the first place via executive actions by former President Trump, nobody should be really surprised when the new President Biden is able to easily remove them. In short, elections have consequences.

However, readers will recall that an effective legal strategy pursued by liberal groups and Democratic states was to challenge Trump’s executive actions, and keep them tangled in federal courts for as long as possible — effectively delaying the implementation of the action for months, even if Trump eventually ended up winning the cases.

Could Republican state Attorneys General now force some of these legal issues back into federal courts, effectively delaying them as happened under Trump in certain cases? Let’s take a look.

On the 2017 travel ban from Chad, Iran, Libya, North Korea, Syria, Somalia, Venezuela and Yemen, former President Trump had acted in accordance with his powers under Article II of the Constitution and 8 U.S.C. 1182(f), which states, “Whenever the President finds that the entry of any aliens or of any class of aliens into the United States would be detrimental to the interests of the United States, he may by proclamation, and for such period as he shall deem necessary, suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrants or nonimmigrants, or impose on the entry of aliens any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate.”

So, it’s a political question with which the President has discretion. It was initially enjoined nationally by a local federal district judge before it was ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court, although the Court never took a position on the nationwide injunction, but did remove much of the injunctions in June 2017, allowing most of the order to take effect while the case was heard, which Trump ultimately won in June 2018. In 2017, Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch had said they would have granted the stays in full — effectively taking a stand against nationwide injunctions.

Suffice to say, with such a clear grant of authority, if Biden wants to lift the travel restrictions, using the same section of law that Trump did, he can. And given the current, clear Supreme Court precedent, there might not be much of a case to make there if anyone were looking to challenge Biden’s authority here.

The same might be said of the border wall construction, which Trump in 2019 declared a national emergency on the southern border and reprogrammed monies for under the 1982 Military Construction Codification Act, which expanded some of the authorities from the 1976 National Emergencies Act, under 10 U.S. Code § 2808(a): “In the event of a declaration of war or the declaration by the President of a national emergency in accordance with the National Emergencies Act (50 U.S.C. 1601 et seq.) that requires use of the armed forces, the Secretary of Defense, without regard to any other provision of law, may undertake military construction projects, and may authorize the Secretaries of the military departments to undertake military construction projects, not otherwise authorized by law that are necessary to support such use of the armed forces.”

As with the travel ban, injunctions were put forth and ultimately stayed by the Supreme Court in 2019 and again in 2020. In the process, the Trump administration managed to construct 450 miles of border wall.

Under the same provisions of law, now President Biden can say the national emergency on the border is over, and stop reprogramming the military construction funds, which he did. There does not look to be much of a case there, either.

As for reentering the World Health Organization, the action former President Trump initially took was under his Article II powers to conduct foreign affairs, generally, and more specifically under 22 U.S. Code § 290c, which states: “In adopting this subchapter the Congress does so with the understanding that, in the absence of any provision in the World Health Organization Constitution for withdrawal from the Organization, the United States reserves its right to withdraw from the Organization on a one-year notice…” That notice was provided, and the withdrawal was set to take effect on July 6, 2021.

But in the same subchapter, under 22 U.S. Code § 290, it clearly states, “The President is hereby authorized to accept membership for the United States in the World Health Organization…” And so, just as easily as Trump could exit WHO, Biden can reenter it, by a plain reading of the law.

On the Paris Climate Accord, if one views it as a treaty, then the Senate never ratified it, and so former President Trump was well within his Article II powers to reject it in 2017. If it is not a treaty, but merely an executive agreement, then Trump was well within his powers to withdraw from it as well.

I take the view that it really was never was a treaty, since it was not legally binding in the first place. It states in Article 4.2. that countries set their own carbon emissions goals: “Each Party shall prepare, communicate and maintain successive nationally determined contributions that it intends to achieve.” And under Article 6.1. it reminds everyone that cooperation is “voluntary”: “Parties recognize that some Parties choose to pursue voluntary cooperation in the implementation of their nationally determined contributions to allow for higher ambition in their mitigation and adaptation actions and to promote sustainable development and environmental integrity.”

President Biden is not saying it is a treaty, either, with the White House issuing a mere statement on Jan. 20: “I, Joseph R. Biden Jr., President of the United States of America, having seen and considered the Paris Agreement, done at Paris on December 12, 2015, do hereby accept the said Agreement and every article and clause thereof on behalf of the United States of America.”

Biden won’t be submitting that for Senate ratification — not that he would have the votes to do so — and so when he is no longer president one day, he shouldn’t be surprised that the next president just does away with it once again.

Finally, on the Remain in Mexico policy by Trump, that was another executive agreement between the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the Government of Mexico dating Jan. 25, 2019. That was done under 8 U.S. Code § 1225(b)(2)(C) provides that “in the case of an alien… who is arriving on land (whether or not at a designated port of arrival) from a foreign territory contiguous to the U.S.,” the Secretary of Homeland Security “may return the alien to that territory pending a [removal] proceeding…”

At the time, the Trump Department of Homeland Security cited “prosecutorial discretion regarding whether to place an alien arriving by land from Mexico in Section 240 removal proceedings…”

This is quite similar to the prosecutorial discretion that the Obama administration cited when it implemented Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals (DACA). In 2017, the Trump administration attempted to rescind DACA, and ultimately, in June 2020, the Supreme Court overturned the Trump action in Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of the University of California, saying that the rescission had not complied with the terms of the Administrative Procedures Act, including requiring a sufficient legal basis for making the changes to the regulation.

Here, the Department of Homeland Security may have a similar problem. It issued a two-paragraph announcement on Jan. 20 of the suspension of the Migrant Protocols without any legal justification whatsoever.

So, using the same precedents, maybe Republican state Attorneys General should test Biden’s suspension in federal court now that the shoe is on the other foot. They could:

First, seek a nationwide injunction by a district judge against the arbitrary suspension of the Remain in Mexico policy, arguing irreparable harm once asylum seekers come into the U.S. and then skip their hearings, disappearing into the country. This would invite federal courts to perhaps finally settle the matter of whether federal district judges really can enjoin implementation of the federal policy nationwide while a case is heard. And in the meantime, force the Biden administration to continue administering the Remain in Mexico policy.

Why not? The Supreme Court has never explicitly disallowed nationwide injunctions, and so states could test the question. We don’t think district judges really can do so under the Constitution and federal law, but until the Supreme Court settles this matter once and for all, it’s fair legally for the states to force the issue. Maybe we’re wrong and they really can, and Republican Attorneys General might as well use the tactic, too.

Let’s watch a Democratic administration decry a nationwide injunction for once.

And second, states could use the same precedent that the Supreme Court blocked DACA from being rescinded with to block the Remain in Mexico from being suspended, citing a complete lack of any legal justification, and then when the government tries to provide them after the fact, ram their post-hoc rationalizations down their throats.

After all, that’s what the Democrats would do — and what’s good for the goose is good for the gander. It’s worth a shot.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.