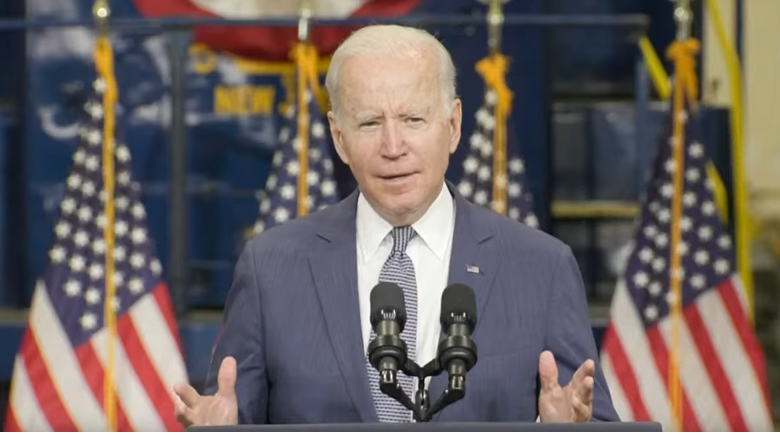

If Biden spends all his political capital on big spending bills, that could mean his legislative agenda is already almost over.

Believe it or not, President Joe Biden’s first term of office is already 20 percent over, and with 2021 almost in the rear-view mirror, his sinking approval rating could mean big trouble for Congressional Democrats looking to keep the barest of majorities in the House and the Senate in 2022.

According to an average of recent polls compiled by FiveThirtyEight.com, Biden averages just 43.5 percent approval among American voters and a rather high 50.6 percent disapproval rating as of Oct. 25.

For the first year in office, that’s pretty bad.

The numbers began turning upside down in July with the emergence of the Delta variant just weeks after Biden had declared America’s independence from Covid on July 4. Inflation has become persistently high. Then, with the botched evacuation of Afghanistan — where over 300 Americans are still said to be stranded behind enemy lines according to the U.S. State Department — public opinion turned against the first-year president.

President Joe Biden will never be as powerful as he is right now, which is saying something. In modern history, presidents tend to focus on their legislative agendas in the first two years, because after the midterms, all bets are off.

In midterm elections dating back to 1906 through 2018, the party that occupies the White House usually loses on average 31 seats in the House, and about three seats in the Senate. That’s more than enough for Republicans to take back one or both chambers of Congress in 2022.

With bare majorities in the House and Senate, then, it’s now or never for Biden’s legislative agenda. So far, though, Biden has just his $1.9 stimulus has been signed into law.

But his plans for a $1.2 trillion infrastructure — with $500 billion of new spending—and another $3.5 trillion spending bill are languishing in the House and Senate. Of the $3.5 trillion, $450 billion would go to universal prekindergarten, $500 billion for universal paid family leave, $111 billion for universal community college with two years paid tuition, $82 billion for retrofitting schools, $80 billion for job training, $500 billion for extending the $3,600 and $3,000 child tax credits, $222 billion for green energy tax credits and another $100 billion or so for forcing Medicaid expansion on 12 states that opted out of Obamacare’s Medicaid expansion.

But Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) has said repeatedly that he won’t vote for anything greater than $1.5 trillion, meaning about 57 percent of the bill has to be cut.

Can Democrats come to a consensus? And even if they do, will Biden have spent all his political capital on big spending bills? That could mean his legislative agenda is already almost over.

So, no eliminating the filibuster.

No amending the Judiciary Act of 1869 to pack the Supreme Court.

No nationalization of election law via H.R. 1 or H.R. 4.

No Green New Deal.

No statehood for D.C. and Puerto Rico.

No bans on hydraulic fracturing.

No public option socialized medicine.

And so forth. Once we’re in 2022, Congressional Democrats will be in a race against time to pass as much and confirm as many judicial appointments as they possibly can before Republicans likely reclaim one or both houses of Congress back in 2022.

While some good news — for example on Covid or the economy — could help to buoy the President’s political fortunes, say, in time for 2024, for 2022, the damage has likely already been done.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.