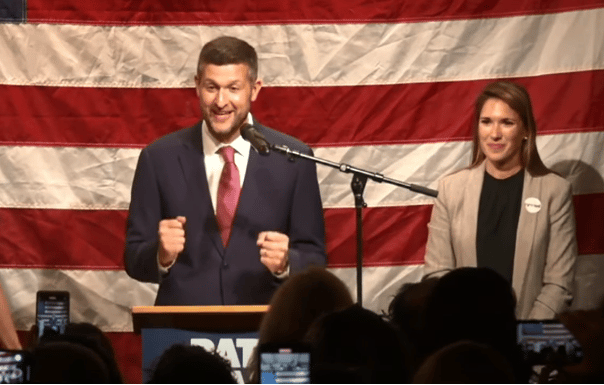

In New York’s 19th Congressional District special election on Aug. 23, Democrat Pat Ryan narrowly defeated Marc Molinaro, 51.1 percent to 48.9 percent.

That’s a seat House Republicans are hoping to pick up certainly in the November Congressional midterms, and yet their hopes were dashed after Molinaro was leading both Republican and Democratic polls of so-called “likely” voters prior to the special election.

On Aug. 17-22, Data for Progress — a Democratic poll — had the race at 53 percent for Molinaro and 45 percent for Ryan.

On Aug. 6-8, DCCC Targeting and Analytics Department — a Democratic poll — had the race at 46 percent for Molinaro to 43 percent for Pat Ryan, with 11 percent undecided.

On July 26-28, Triton Polling & Research — a Republican poll — had the race at 50 percent for Molinaro and 40 percent for Ryan, with almost 11 percent undecided.

On June 29-30, Public Policy Polling—a Democratic poll—had the race at 43 percent for Molinaro to 40 percent for Ryan with 16 percent undecided.

On June 16-20, Triton had the race at 52 percent for Molinaro to 38 percent for Ryan, with 10 percent undecided.

Every single poll was wrong, on both sides. Republicans overstated their advantage, and Democrats understated theirs. In other news, Republican Joe Sempolinski seemed to easily win the U.S. House special election for New York’s 23rd Congressional District, but it might have been closer than expected.

Given Ryan’s close win, the lesson appears to be that perhaps the “likely” Republican voters are still likely voters, but that “likely” Democratic voters identified in polls understated Democratic turnout by several points. That’s important to consider as November rapidly approaches. Why?

A look at national, generic Congressional ballot polls currently shows Democrats leading in polls taken of simply registered voters, while Republicans are favored in polls of “likely” voters.

For example in late July and throughout August, CBS News Battleground Tracker, InsiderAdvantage, Trafalgar Group and Rasmussen Reports all had polls of “likely” voters with Republicans appearing to be somewhat or safely ahead in the generic Congressional ballot.

Whereas, Politico/Morning Consult, Economist/YouGov and Monmouth polls of registered voters in recent weeks have been showing Democrats leading, particularly since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. An exception is NBC News’ most recent poll taken Aug. 12-16, showing Republicans leading 47 percent to 45 percent.

Normally, in a midterm election cycle, the opposition party has the advantage. In midterm elections dating back to 1906 through 2018, the party that occupied the White House lost seats in the House 90 percent of the time, with losses averaging 31 seats. The exceptions were 1934, 1998 and 2002, when the incumbent party was able to pick up seats in the House.

In the Senate, the incumbent party lost seats 70 percent of the time, with losses averaging three seats in the Senate.

A great deal of that has to do with the incumbent party’s voters relaxing after winning a presidential election, whereas the opposition party cannot wait to vote so that they do not remain out of power. It’s fatigue versus anxiety. Usually, the incumbent party becomes a victim of its own success.

So, what’s happening? Perhaps, similar to the 2020 presidential election, more than one predictive model could be colliding into another. In 2020, former President Donald Trump had a lot of momentum on the campaign trail and managed to increase his 2016 vote count by about 13 million. Normally, that should have been enough to win, but there was also Covid and a massive recession that temporarily threw 25 million people out of work, plus pandemic restrictions led to more mail-in ballots being used, both of which appeared to favor Democratic turnout. The outcome was Biden winning narrowly amid record turnout for both parties.

And that’s really the trick to beating either presidential incumbency advantage but also the opposition party’s advantage in midterm election cycles. It’s rare but it happens and 2022 like any other year could always add to that exception. Whichever party is at a disadvantage in those cycles must always find a way to overcome those currents to either minimize losses or to maximize advantage. That’s why we play the game.

In this case, given that polling in New York 19th Congressional District was so wrong, that anyone modeling “likely” turnout in the Congressional midterms should still account for boosted Republican enthusiasm, but now may also need to account for some underpolled segment of Democrats.

Or in November, House Republicans might find themselves in the rare company of 9/11 era Democrats, Clinton impeachment era Republicans and Great Depression Republicans, parties that should have perhaps picked up seats in 2002, 1998 and 1934 but were unable to do so owing to exceptional historical circumstances — and be very surprised by the outcome.

Now, it was a special election, too, and so that must be accounted for. Plus, it’s a brand new Congressional district. But the pollsters almost certainly took those into consideration.

Point is, likely voters may not be who you think they are this year.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.