Consumer inflation remains elevated 6.4 percent over the past 12 months, with a 0.5 percent increase in January, according to the latest data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Food was up 0.5 percent—and 10.1 percent for the past year.

Energy was up 2 percent, including a 2.4 percent jump in gasoline. Overall, it’s up 1.5 percent the past year at current levels.

Also, utility gas service was up 6.7 percent, following a 3.5 percent jump in December. It’s up 26.7 percent the past year.

Shelter was up 0.7 percent—up 7.9 percent the past year.

And transportation was up 0.9 percent, with a 14.6 percent jump the past year.

The continued, elevated, upward movement in prices comes as the Federal Reserve has decreased the size of its interest rate hikes.

In its Feb. 1 meeting of the Board of Governors, the Fed kept hiking its own policy rate, now reaching 4.5 to 4.75 percent, and it’s not over yet as the central bank said it “anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range” could be necessary going forward.

According to the central bank’s statement, “the Committee decided to raise the target range for the federal funds rate to 4-1/2 to 4-3/4 percent. The Committee anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time.”

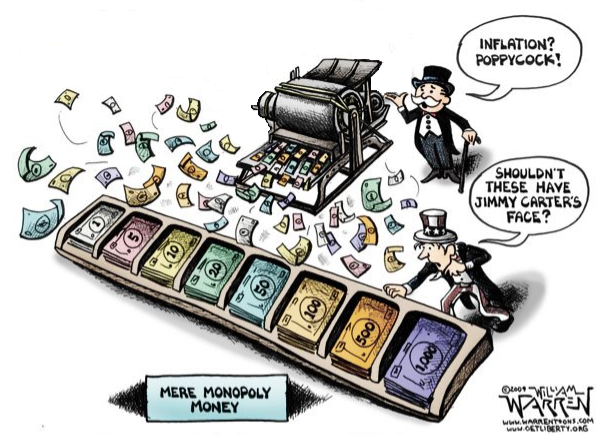

The truth is there’s still a lot of excess dollars in the system left over from the Covid monetary expansion, where more than $6 trillion was spent, borrowed and printed into existence to offset the economic lockdowns, production halts and the temporary spike in unemployment, where 25 million Americans lost their jobs.

As a result the M2 money supply increased dramatically from $15.3 trillion in Feb. 2020 to a peak of $22 trillion by April 2022, a massive 43.7 percent, leading to the inflation spike, where consumer inflation reached 9.1 percent in June 2022. In fact, by the time Russia invaded Ukraine in Feb. 2022—further worsening global supply issues—consumer inflation was already north of 7.5 percent.

The inflation was going to happen anyway. It was too much money ($6 trillion) chasing too few goods (Covid production halts).

Even at the Fed’s current elevated interest rates, the M2 money supply has now decreased from its highs to $21.3 trillion, but is that enough to cool off the inflation and return to price stability? Perhaps hoping not to pop the bubble on its own, the Federal Funds Rate still remains a couple points below the consumer inflation rate, as the central bank appears to be cautiously hoping inflation will come down on its own.

But that usually happens in recessions with the unemployment rate spiking. Unemployment is still at quite historic lows of 3.4 percent. That might explain the sticky high prices, but also the ongoing labor shortages as the Baby Boomers continue retiring en masse.

In that sense, the U.S. economy looks more like a wartime economy than anything else. There, the civilian labor shortages are caused by drafts, artificially lowering the pool of working age men and relatively lower unemployment rates. In the current case, the labor shortages are caused by poor long-term fertility, which in the U.S. is down to 1.63 babies per woman in 2020 and dropping, below the replacement rate. It went down below 2 babies per woman in 2010, and it’s been 13 years, and so the resulting labor force declines will not even begin to be felt for another three years, and then should be continuing to be felt for several years to come.

Those are simultaneous inflationary and deflationary pressures, which if policy makers cannot figure out what the downstream effects of both are, could keep them guessing. But what the Fed usually does is treat the symptoms. Inflation remains elevated, and so expect more interest rate hikes. And then when the recession comes, expect them to lower rates again. It could be a bump road ahead. Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.