“A no-strings-attached debt limit increase will not pass.”

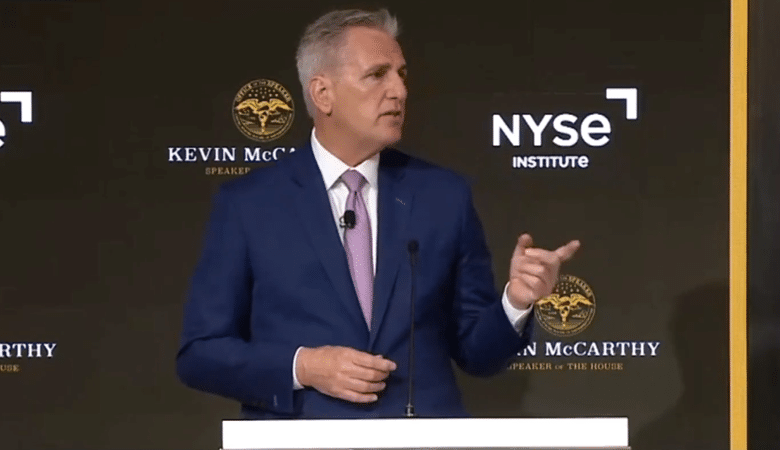

That was House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) in a speech to the New York Stock Exchange on April 17 foreshadowing the upcoming debate in Congress on increasing the $31.4 trillion national debt ceiling as the new House Republican majority attempts to restore some semblance of fiscal responsibility to Congress.

House Republicans have previously stated that they would like to keep discretionary spending at 2022 levels. That was $1.664 trillion on the baseline according to the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

For 2023, discretionary spending is projected to rise to $1.736 trillion. So, the Republican plan is to cut $72 billion out of the total projected to be $6.376 trillion.

That’s just 1.1 percent of the total budget, and about 4.15 percent of the so-called discretionary budget.

As far as cuts go, this does not even cover the increased cost of interest payments owed on the national debt, which on a net basis will increase to $665 billion in 2023, $794 billion in 2024 and $842 billion in 2025.

And yet, McCarthy’s pitch for just a one-year freeze of the discretionary budget is about the only game in town when it comes to reinstating fiscal sanity in Washington, D.C.

McCarthy opened the door for negotiations in his speech, stating, “Debt limit negotiations are an opportunity to examine our nation’s finances.” Sounds reasonable.

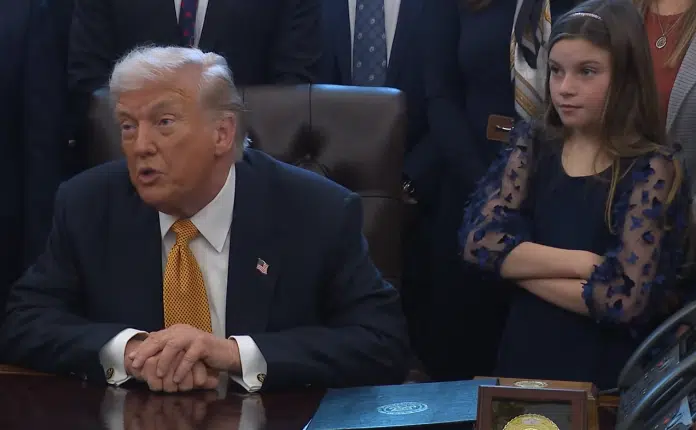

But where is President Joe Biden? So far, he’s talking through surrogates.

The last substantive thing we heard from the White House directly on the debt ceiling was Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre on Jan. 20, stating, “Like the President has said many times, raising the debt ceiling is not a negotiation; it is an obligation of this country and its leaders to avoid economic chaos. Congress has always done it, and the President expects them to do their duty once again. That is not negotiable.”

So, the opening bid from the White House is there will be no discussion, no negotiation and no deal when it comes to how to get our unsustainable fiscal picture under control.

The real problem is that, thanks to declining fertility since the advent of birth control, the population since the Baby Boomers has not grown fast enough to keep up with the current wave of Baby Boomers now retiring. It has not been above two babies per woman — the population replacement rate — since 2009. Nor has immigration kept up from countries similarly affected by declining fertility.

As it is right now the White House is projecting the $31.4 trillion debt will hit $50 trillion by 2033.

But that really depends on how many and how bad the recessions we have between now and then really are, which result in countercyclical spending by Congress, plus whatever new wars the U.S. finds itself embroiled in. The truth is, since 1980, the national debt has grown by more than 8.8 percent a year. At that rate, the national debt could hit $100 trillion as soon as 2036 or 2037.

Either way, $50 trillion by 2033 or $100 trillion by 2037 or beyond, this will mean is that we’re going to need much larger financial institutions — that is, bigger banks — in order to accommodate what is going to be a booming national debt and treasuries market for the rest of our natural lives.

Why? We’ve already established we’re not having more children, which means relatively fewer taxpayers and so we’ll alternatively have to commit to ever more borrowing. Raising taxes on a dwindling labor force would strangle the middle class and impose serious burdens on the health of the U.S. economy.

Don’t expect a foreign bailout. In the Dec. 2008, foreign central banks and financial institutions owned $3 trillion out of the $9.9 trillion national debt, or 30.8 percent. In Jan. 2023, they owned $7.4 trillion out of the $31.4 trillion debt, or 23.5 percent. They percentage they own has declined even as the amount they have bought has increased. They cannot keep up with our borrowing.

In that time, to offset the net slowdown of foreign investments in the debt, the Fed took its share of the debt from $790 billion in Aug. 2007 when the global financial crisis began, or 8.8 percent of the then $8.9 trillion national debt, to $5.28 trillion out of the $31.4 trillion debt as of April 2023, or 16.8 percent. It’s almost doubled. So, there will be printing but we won’t want to do too much of that because, as we’ve discovered since Covid, printing money to pay the debt is highly inflationary.

The current $6.7 trillion of debt held by the Social Security, Medicare and other trust funds is also a dwindling share of the debt, from $4.3 trillion out of $9.9 trillion in Dec. 2008, or 43 percent, to $6.8 trillion out of $31.4 trillion, down to 21.6 percent. Plus, as the trust funds are exhausted over the next decade or so, that number will be steadily declining. In any event, McCarthy stated his proposals to cut spending will be “all without touching Social Security or Medicare.” So, we won’t be able to get the money from there.

That leaves U.S. financial institutions, retirement funds, mutual funds and so forth with its share of treasuries rising from about 17 percent in 2008, or $1.7 trillion, to a massive $11.9 trillion, or 38 percent today — the largest single holder of the debt.

In a way, it is appropriate that Speaker McCarthy delivered his speech to financial institutions at the New York Stock Exchange.

Because almost all of the money we need to finance the national debt going forward will have to come from there with ever larger banks in the U.S., which will likely mean more regulation, more capital controls (i.e. digital currency), higher insurance premiums and fees, and much larger asset prices to keep the financial system solvent — and very likely less liberty. Maybe that’s the idea.

We’re staring into an abyss.

That is the true discussion we are already having right now, without any meeting between Speaker McCarthy and President Biden having even taken place yet. But when they do meet, and I do hope it is soon, perhaps some of the factors leading to our current unsustainable financial burdens, including declining fertility and increased reliance of U.S. financial institutions, will be brought to the table, as well as some of the consequences if Washington, D.C. cannot restore some measure of sovereign control over what is becoming a grave threat to the financial freedom of all Americans — and to our national security when we consider what we’d have to do to ever finance a much larger war.

But I have a feeling President Biden won’t even want to discuss cutting just $72 billion for a year, or the perfectly reasonable 1.1 percent cut that Speaker McCarthy is putting on the table. In the meantime, it appears the U.S. ship of state will continue to plunge into the abyss.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.