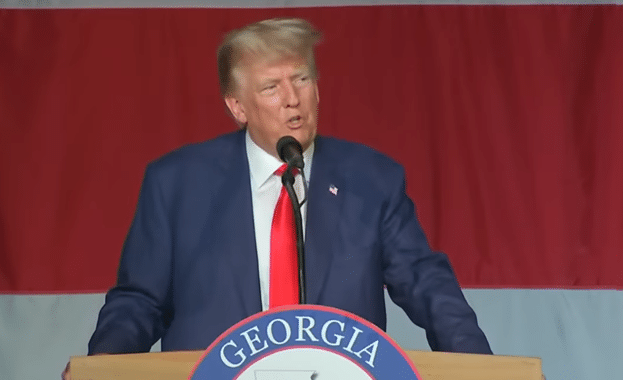

Fulton County, Ga. prosecutors have issued their own indictment of former President Donald Trump on Aug. 14 on alleged racketeering violations over his challenge of the 2020 election in Georgia, coming atop a similar federal indictment by Special Counsel Jack Smith over Trump’s challenges nationwide and attempts to persuade states, courts, Congress and the Vice President to intervene on his behalf.

The Fulton County indictment is similarly drawn, including under the heading, “Manner and Methods of the Enterprise,” several speech and petition-related “crimes”: “False Statements to and Solicitation of State Legislatures,” “False Statements to and Solicitation of High-Ranking State Officials,” “Creation and Distribution of False Electoral College Documents,” “Members of the enterprise, including several of the Defendants, falsely accused Fulton County election worker Ruby Freeman of committing election crimes in Fulton County, Georgia. These false accusations were repeated to Georgia legislators and other Georgia officials in an effort to persuade them to unlawfully change the outcome of the November 3, 2020, presidential election in favor of Donald Trump,” “Solicitation of High-Ranking United States Department of Justice Officials,” and “Solicitation of the Vice President of the United States.”

There’s one basic problem with these specific charges. They are all related to Trump challenging the results of the 2020 election, and attempting to persuade government officials, including courts, state legislators and prosecutors to investigate what the Trump campaign was alleging were election law violations, and to otherwise submit an alternate slate of electors to Congress when it was to convene on Jan. 6, 2021. That’s all political speech protected by the First Amendment.

Specifically, the rights to freedom of speech and to petition the government for a redress of grievances. The full amendment states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

That’s what Trump is accused of doing, to wit, “in an effort to persuade” the state of Georgia to change its slate of electors even though Trump and his campaign had an absolute right to “persuade” the state, even if the effort failed or even if the effort was based on any erroneous information.

Trump also had a right to convene alternate slates of electors, as happened in the presidential elections of both 1876 that led to the election of Rutherford B. Hayes, prior to the passage of the Electoral Count Act in 1887, and in 1960 in Hawaii, afterward, when both parties in contested states put forward competing slates of electors that Congress had to later sort out. Congress never prohibited convening alternate slates of electors.

In fact, Electoral Count Act, the very process that was used in every election thereafter, including on Jan. 6, 2021 didn’t prohibit election challenges, and it didn’t prohibit convening alternate slates of electors, and instead created a process that states and Congress would follow in the event there were such disputes and controversies over who won a state’s election, leaving the final determinations to the states to certify electors and to Congress to hear objections, even if the objections were based on erroneous grounds.

As noted by the Congressional Research Service in Aug. 2022 on false speech laws as it relates to the First Amendment: “a law is presumptively unconstitutional unless the government can show the challenged law is the least restrictive means of targeting speech while also serving a compelling governmental interest. Courts have sometimes extended this general principle to laws regulating false speech and concluded that laws prohibiting lies about a certain topic trigger strict scrutiny.”

In this case, “least restrictive” would mean the state of Georgia following the process outlined by the Electoral Count Act, which ultimately resulted in Georgia awarding its electors to President Joe Biden. There was a challenge to be considered on the floor of Congress on Jan. 6, 2021, but support from the Senate was withdrawn after to the riot at the U.S. Capitol, even while challenges to Arizona and Pennsylvania were still heard in accordance with the law.

There are also allegations of attempting to audit Coffee County-based voting machines and voting records in an agreement with data company SullivanStrickler LLC “by downloading said data from a server maintained by SullivanStrickler LLC.” SullivanStrickler LLC was hired “for the performance of computer forensic collections and analytics on Dominion Voting Systems equipment in Michigan and elsewhere.”

But election machines do not contain “employment, medical, salary, credit, or any other financial or personal data relating to any other person” as defined in O.C.G.A. 16-9-93(c) but rather anonymized voting tabulations and the software that makes it work.

Was it even data Georgia was responsible for maintaining? The indictment mentions the company’s Michigan voting machine audit and that the data was not downloaded from Georgia state systems but rather “a server maintained by SullivanStrickler LLC.”

As for voter registration information, those are public records in the state of Georgia.

Pursuant to O.C.G.A. 21-2-225(b), “all data collected and maintained on electors whose names appear on the list of electors maintained by the Secretary of State pursuant to this article shall be available for public inspection” except for bank records, Social Security numbers, email addresses, driver’s license numbers, etc. which are not located in voter files.

According to Georgiasecretaryofstate.net, “By law, voter registration lists are available to the public and contain the following information: voter name, residential address, mailing address if different, race, gender, registration date and last voting date. The Statewide Voter List does not include telephone numbers, date of birth, Social Security number or Drivers License number. The Statewide Voter List includes Active and Inactive Voters.” A statewide voter list is available for purchase for $250.

While it is unclear from the indictment what personal data was allegedly accessed — nowhere does the indictment does not mention bank records, Social Security numbers, email addresses, driver’s license numbers, etc. being accessed from Georgia’s election systems — if it was data that SullivanStrickler LLC had purchased from the Secretary of State’s office, or was data that was otherwise a public record, and not information which is excepted by the law, or if it was even Georgia’s data that was allegedly accessed. It is therefore hard to see how Georgia’s confidential records were breached, if at all.

Finally, Trump and his campaign are accused of perjury in various court pleadings throughout the state, again over his contestation of the 2020 election results. But even if the challenges were based on erroneous allegations, as is alleged, this again seeks to criminalize what otherwise amounts to political speech and the right to challenge election results in courts of law, all protected by the First Amendment. Petitioning the government is not limited to the legislative branch, but all three branches of the government, and challenging elections is political speech.

Perhaps when Trump pleads “not guilty” Fulton County will call that a crime, too.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.