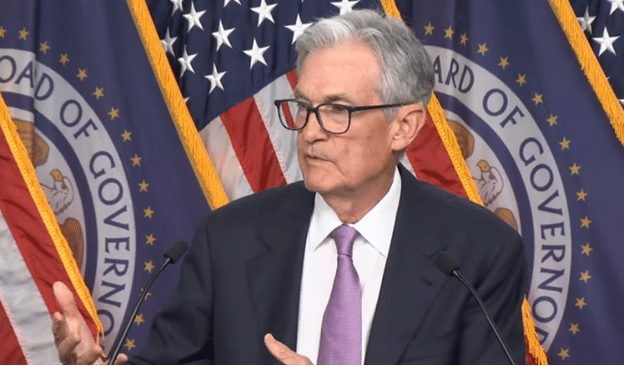

“As inflation has declined and the labor market has cooled, the upside risks to inflation have diminished and the downside risks to employment have increased.”

That was Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell at his Sept. 18 press conference on the heels of cutting the Federal Funds Rate to 4.75 percent to 5 percent, acknowledging the basic reality that the U.S. economy, in particular, U.S. labor markets after peak inflation are in a cycle of shedding jobs.

This is what usually happens when the economy hits a high in inflation — it peaked at 9.1 percent annually in June 2022 — and then households max out their credit cards, consumption slows down and, inevitably, job openings slow and layoffs begin to kick in.

At that point, historically, the Fed begins cutting interest rates, sometimes ahead of a slowdown or recession, sometimes during such a downturn, but it always ends up in the same spot.

Interest rates will come down amid the cooler rate of inflation — although it’s worth noting that prices are still well above their pre-inflation levels — and then, if and when labor market conditions worsen, the Fed will keep cutting rates until as inflation bottoms and then the new, lower rate will be parked until such time as inflation goes above the Fed’s 2 percent mandate levels, and then the interest rate hiking cycle begins anew.

Another way of looking at it, particularly early in the process, is that decisions for further rate cuts are predicated on worsening labor market conditions, emphasizing the Fed’s dual mandate, such that the higher the unemployment rate ticks up, the more rate cuts the Fed will initiate.

Historically, this has also been true, reflecting the inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment — although occasionally, inflation can tick up really fast, immediately overheat the economy and unemployment spikes up rapidly, as happened during the 1970s and in 1980.

But it’s still reflecting the same phenomenon, which is that too much inflation is bad for the economy, dries up consumer activity and then as prices come down, the layoffs ensue. The inverse is also true, when deflation occurs, because there is no demand, unemployment will go to the moon. The American people got a brief taste of that in 2020, with the Covid economic lockdowns that saw 25 million jobs temporarily displaced as commodities like oil went below $0 per barrel.

It was also true during the Great Depression, when economies in the West were coming off the interwar gold standard, the still-on-gold dollar strengthened dramatically, sparking deflation as mass unemployment, with the unemployment rate spiking up to 25 percent. The U.S. came off the gold standard in 1933, inflation was restored, and unemployment trended down to 11 percent until there was another recession, deflation resumed, and unemployment spiked up again to 20 percent by 1938. By then, World War II had begun, the U.S. ramped up wartime production, initiated the draft, inflation spiked and unemployment was temporarily defeated.

After both the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Great Inflation of the 1970s, the Fed has sought to achieve its dual mandate, attempting to avoid the extremes of both inflation and deflation, aiming for price stability with varying degrees of success.

Most recently, following the brief Covid recession, the Fed oddly left interest rates near zero percent even as inflation was zooming upward in 2021 amid a torrent of federal spending, borrowing and printing almost $7 trillion plus demand resuming faster than expected as the global supply chain crisis was exacerbated.

By the time Russia invaded Ukraine in Feb. 2022, U.S. consumer inflation was already 7.5 percent, and the Fed still had not hiked interest rates, which it began doing in March 2022 and finishing off in July 2023 and maintaining that posture until Sept. 18, 2024.

Now, as Powell is acknowledging, we’re on the other side of that equation, stating that labor markets are now expected to worsen greater than expected: “In the labor market, conditions have continued to cool. Payroll job gains averaged 116,000 per month over the past three months, a notable stepdown from the pace seen earlier in the year. The unemployment rate has moved up but remains low at 4.2 percent. Nominal wage growth has eased over the past year, and the jobs-to-workers gap has narrowed. Overall, a broad set of indicators suggest that conditions in the labor market are now less tight than just before the pandemic in 2019. The labor market is not a source of elevated inflationary pressures. The median projection for the unemployment rate in the SEP is 4.4 percent at the end of this year, four-tenths higher than projected in June.”

As a result of weakening labor market conditions, or “cooling” as Powell put it, more rate cuts are expected: “In our SEP, FOMC participants wrote down their individual assessments of an appropriate path for the federal funds rate based on what each participant judges to be the most likely scenario going forward. If the economy evolves as expected, the median participant projects that the appropriate level of the federal funds rate will be 4.4 percent at the end of this year and 3.4 percent at the end of 2025. These median projections are lower than in June, consistent with projections for lower inflation and higher unemployment, as well as the change to balance of risks.”

Meaning, much of the unemployment still remains on the horizon, no matter who wins the election in November between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump. Even with Powell’s projections that the U.S. economy is “strong” relative to other economies, what matters to American households is just how bad will the downturn in labor markets be, just how high will unemployment really go and when and therefore how bad the pain is. We’ll find out soon enough. Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.