“It’s going to mean tremendous amounts of jobs and ultimately prices will stay the same, go down but we’re going to have a very dynamic country.”

That was President Donald Trump in the Oval Office on Feb. 13 taking questions from reporters, outlining his belief that one of the outcomes of imposing reciprocal tariffs on trading partners, including steel and aluminum tariffs set for March 12, is that ultimately consumer prices can come down.

Although in the short term, there could be some volatility, Trump explained, stating, “I think what’s going to go up is jobs are going to go up and prices could go up somewhat short term, but prices will also go down.”

To be certain, when the Consumer Price Index is calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, it does indeed include sales and excise taxes, and so certainly, in the short term, any immediate increases in taxes charged whether at the wholesale or consumer level, could in the short term feed back into the recorded consumer prices. But that’s not where the story ends.

Often times, in response to trade adjustments like tariffs (and others like subsidies), trading countries can depreciate their currencies in order to still make exports cheaper. This can have the impact of making the trading partner’s currency weaker relative to the importing country’s which becomes stronger.

If that happens, that might mean the dollar becomes stronger as trading partners respond overseas with devaluations, which would ultimately put downward pressure on consumer prices. Especially with the dollar remaining the world’s reserve currency, these adjustments can be even more pronounced.

For example, since the Feb. 1 increase of tariffs on Chinese goods by President Trump by another 10 percent, coming atop 25 percent on $250 billion of goods and 17.5 percent on the remaining $300 billion of goods that were established by Trump in 2019 that President Joe Biden never rescinded, China has in fact devalued its currency against the dollar, dropping from .1391 yuan per dollar to .1372 as of this writing, a 1.36 percent decrease.

Meaning, Trump is right. Tariffs can be increased by the U.S., and if the trading partner responds with devaluation, as China already has, it can partly or in full offset the adjustment, meaning the U.S. still collects the revenue but as Trump suggested prices could “stay the same, go down…”

There are other historic examples of this. From the nation’s founding through the 1920s, the U.S. almost exclusively collected revenue from tariffs, becoming the manufacturing center of the world and enriching America to be one of the richest countries in the world. But upsetting that ascent was the Great Depression in the 1930s as countries began competitively devaluing their currencies by leaving the interwar gold standard one by one, led by the United Kingdom in 1931.

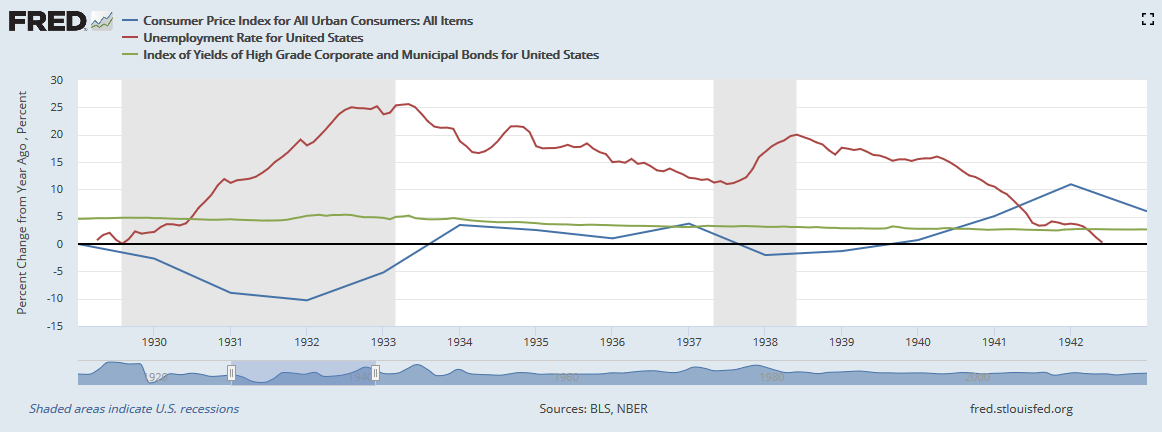

Prior to that, deflation in the U.S. had already begun after the great inflation of World War I and the ensuing credit expansion, had a brief respite in the 1920s before beginning again in 1927. It then slowed in 1929, and then went crazy starting in 1930 as banks began failing en masse. Inflation was marked at -2.7 percent in 1930, -8.9 percent in 1931, -10.3 percent in 1932 and -5.2 percent in 1933.

As that occurred, unemployment skyrocketed, reaching 11.2 percent by the end of 1930, up to 19.2 percent by the end of 1931, up to 25 percent in 1932 and peaked in March 1933 at 25.4 percent.

It was not until Franklin Roosevelt ended the interwar gold standard in 1933, thereby weakening the dollar against that of U.S. trade partners, that some relief was felt as unemployment began collapsing to 11 percent by 1937, before spiking again in the 1937 and 1938 recession as deflation ensued again. The U.S. would not again return to full employment until World War II.

The United Kingdom had a similar experience of deflation following World War I, with unemployment rising dramatically in 1921 to 11 percent before dropping and again rising in 1930 to 11 percent. The UK quickly came off the gold standard in 1931, after which unemployment peaked in 1932 at 15 percent, before slowly coming back down.

In fact, countries that abandoned the gold standard early and engaged in currency devaluation and depreciation to combat the deflation saw the quickest recoveries. The countries that were the last to devalue were the worst off, a 1985 paper, “Exchange Rates and Economic Recovery in the 1930s,” by economists Barry Eichengreen and Jeffrey Sachs found.

What was the impact of the devaluations? Eichengreen and Sachs observe, “In all cases of unilateral devaluation, currency depreciation increases output and employment in the devaluing country. By raising the price of imports relative to domestic goods, depreciation switches expenditure toward domestic goods. The increased pressure of demand will tend to drive up domestic commodity prices, moderating the stimulus to aggregate demand and (by reducing real wages) stimulating aggregate supply, until the domestic commodity market clears. The same effect switches demand, of course, away from foreign goods, exerting deflationary pressure on the foreign economy.”

So, because the UK was one of the first major economies to leave the interwar gold standard in 1931, it boosted exports and restored inflation and then unemployment began dropping.

Note that 1931, as the UK went off the gold standard, was the same year inflation in the U.S. went from -2.7 percent to -8.9 percent and unemployment went from 11.2 percent to 19.2 percent. A good question might be what impact the UK’s devaluation in 1931 and other countries leaving the gold standard had on the U.S., which did not devalue and depreciate until beginning in 1933? In that context, the uneven devaluations of certain countries may have exacerbated the Great Depression in other countries that waited to devalue.

On the issue of tariffs, in 1932, a year after coming off the gold standard, the UK implemented a pretty hefty tariff. In the years that followed, however, unemployment in the UK dropped from 15 percent to 13.9 percent in 1933 and 11.7 percent in 1934. There was no retaliatory reverberation that worsened the UK’s experience. At that point, the U.S. enacted the Reciprocal Trade Act, and was already off the gold standard, and the competitive devaluations and tariffs could begin to get under control as countries sought to stop the trade war.

Obviously the Great Depression is a worst case scenario, wherein disorderly competitive devaluations were so powerful — and mismanaged — that they sent shockwaves throughout the global economy. But not every devaluation has had such impacts. Since Bretton Woods, trade partners like Japan, South Korea, Mexico, etc. have routinely used devaluations to cheapen exports, with the impact simply leading to the U.S. offshoring production and manufacturing jobs.

In any event, the current problem globally since Covid have been production shortfalls and a global supply chain glut, coupled with monetary and fiscal stimulus totaling trillions of dollars — too much money chasing too few goods — so not deflation, but inflation.

One way to potentially deal with that is are items like higher interest rates by central banks, which have already been done, but now President Trump is suggesting that interest rates could start to come down once his tariffs are taken into consideration. Why? Because collecting taxes, wherever the source, takes money out of circulation.

Another mechanism to sop up excess money also performed by central banks is to sell treasuries, which the Federal Reserve has been doing since 2022, decreasing its treasuries holdings from $5.77 trillion in June 2022 to $4.26 trillion on Feb. 12, 2025, a 35 percent decrease and sopping up more than $1.5 trillion out of the money supply.

Similarly, President Trump recently announced his intention to explore creating a sovereign wealth fund in the U.S. One of the likely sources of funding for such an endeavor might include the some $7.3 trillion of intragovernmental holdings of non-marketable U.S. treasuries. Right now those government trust funds are just holding government paper, but there’s really nothing stopping the U.S. from converting them into marketable securities and potentially selling them. This too would take more money out of circulation, which would also strengthen the dollar.

In other words, even as the U.S. increases revenues from tariffs, that is not the only consideration when it comes to measuring inflation. There are offsetting policies that might impact on inflation in the longer term, including policies that impact on the value of the dollar, which is still king, and President Trump knows it.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.