In the dead of night, the Supreme Court on April 19 entered a sweeping order barring all further deportations by President Donald Trump and the federal government under the 1798 Alien Enemy Act: “The Government is directed not to remove any member of the putative class of detainees from the United States until further order of this Court.”

The apparent 7-2 to ruling — Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas dissented — effectively blocking President Trump from acting on his March 15 proclamation that Venezuela and its proxies including the criminal drug cartel terrorist gang Tren de Aragua are “perpetrating, attempting, and threatening an invasion or predatory incursion against the territory of the United States.”

The President certainly has power to declare that there is such an invasion under 50 U.S. Code Sec. 21, enacted by Congress in 1798, stating, “Whenever there is a declared war between the United States and any foreign nation or government, or any invasion or predatory incursion is perpetrated, attempted, or threatened against the territory of the United States by any foreign nation or government, and the President makes public proclamation of the event, all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of the hostile nation or government, being of the age of fourteen years and upward, who shall be within the United States and not actually naturalized, shall be liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured, and removed as alien enemies.”

And President Trump has thus far treated the invasion as a military matter in his Jan. 20 national border emergency declaration under the National Emergencies Act including the deployment of the U.S. military under 10 U.S. Code Sec. 12302, “Ready Reserve,” which allows up to 1 million active duty military to be used and to finish construction of the southern border wall under 50 U.S. Code Sec. 1631 and 10 U.S. Code. Sec. 2808, which allows for military construction authorities to be invoked in the event of a national emergency.

Trump also declared Tren de Aragua, MS-13 and other criminal gangs and drug cartels as terrorist organizations on Jan. 20 by executive order in accordance with 8 U.S. Code Sec. 1189, “Designation of foreign terrorist organizations.”

The 1952 and 1965 Immigration and Nationality Acts never repealed the 1798 Alien Enemy Act. Instead, the 1952 act explicitly invoked it and excepted enemy aliens from being permitted to enter the U.S.: “the following classes of aliens shall be ineligible to receive visas and shall be excluded from admission into the United States… Aliens who have been arrested and deported… or who have been removed as alien enemies…”

And while the 1965 Act did amend this provision in 8 U.S. Code Sec. 1182 — it no longer mentions “alien enemies” as being inadmissible — the law still contains very similar provisions, specifically for aliens designated as terrorists, in subsection (a)(3)(B) as also being inadmissible: “Any alien who.. has engaged in a terrorist activity… is inadmissible.” Which, the President has done.

However, despite the President militarizing the operation and naming the terrorist targets as it relates to the invasion that he singularly has the power to proclaim and to interdict, the Supreme Court has suspended enforcement of the law under the Alien Enemy Act — ostensibly so that every invader and every illegal alien being targeted by President Trump for mass deportation (let’s just cut to the chase, this is about preventing Trump from implementing his removal program writ large) will get a “due process” hearing under the Fifth Amendment.

In other words, regardless of whatever laws Congress has already passed to see to the expedited removals of illegal, inadmissible aliens by the executive branch, the Court appears to be setting the predicate that as a constitutional matter, all immigration laws allowing for expedited removals without hearings are now unenforceable. All wars — which deprive people of their lives without hearings, too, via the use of force, even when Congress authorize it — must similarly be suddenly unfightable, right?

But why stop at removals? What about those deemed inadmissible under 8 U.S. Code Sec. 1182, who are barred from even entering the country without any hearing whatsoever, just an executive determination that they do not meet the criteria for entry into the U.S.?

For example, under 8 U.S. Code Sec. 1225(c) it states that inadmissible aliens can be immediately removed: “If an immigration officer or an immigration judge suspects that an arriving alien may be inadmissible under subparagraph (A) (other than clause (ii)), (B), or (C) of section 1182(a)(3) of this title, the officer or judge shall—(A)order the alien removed, subject to review under paragraph (2); (B)report the order of removal to the Attorney General; and (C)not conduct any further inquiry or hearing until ordered by the Attorney General.”

And 8 U.S. Code Sec. 1225(c) provides the Attorney General can remove the alien without a hearing: “The Attorney General shall review orders issued … If the Attorney General… is satisfied on the basis of confidential information that the alien is inadmissible under subparagraph (A) (other than clause (ii)), (B), or (C) of section 1182(a)(3) of this title, and … after consulting with appropriate security agencies of the United States Government, concludes that disclosure of the information would be prejudicial to the public interest, safety, or security, the Attorney General may order the alien removed without further inquiry or hearing by an immigration judge.”

In sum, all that is necessary is that the Attorney General make the determination that the alien is inadmissible under security related grounds, similar to the President’s determination that there is an invasion and that there are invaders to be removed. These are solely executive branch determinations. Or at least, they were.

8 U.S. Code Sec. 1182(a)(3) are those aliens inadmissible on “Security and related grounds” including “Any alien who a consular officer or the Attorney General knows, or has reasonable ground to believe, seeks to enter the United States to engage solely, principally, or incidentally in … any activity … to violate any law of the United States relating to espionage or sabotage or … to violate or evade any law prohibiting the export from the United States of goods, technology, or sensitive information … any other unlawful activity, or … any activity a purpose of which is the opposition to, or the control or overthrow of, the Government of the United States by force, violence, or other unlawful means, is inadmissible.”

Or any aliens the Attorney General finds to be terrorists: “Any alien who … has engaged in a terrorist activity; … a consular officer, the Attorney General, or the Secretary of Homeland Security knows, or has reasonable ground to believe, is engaged in or is likely to engage after entry in any terrorist activity… [or] has, under circumstances indicating an intention to cause death or serious bodily harm, incited terrorist activity; … is a representative … of … a terrorist organization … or … a political, social, or other group that endorses or espouses terrorist activity; … endorses or espouses terrorist activity or persuades others to endorse or espouse terrorist activity or support a terrorist organization; … has received military-type training … from or on behalf of any organization that, at the time the training was received, was a terrorist organization … [or] is the spouse or child of an alien who is inadmissible under this subparagraph, if the activity causing the alien to be found inadmissible occurred within the last 5 years, is inadmissible.”

Every year, there are over 20,000 such expedited removals according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection data compiled by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse of such inadmissibles without any hearing as Congress provided — 23,957 in 2014, 25,967 in 2015, 30,346 in 2016, 32,941 in 2017, 30,988 in 2018, 30,852 in 2019, 21,578 in 2020, 23,262 in 2021, 21,978 in 2022, 21,519 in 2023 and 21,998 in 2024 — that had never been barred as a “putative” class by federal courts, and certainly not the Supreme Court, until now.

In his dissent, Justice Alito stated, “literally in the middle of the night, the Court issued unprecedented and legally questionable relief without giving the lower courts a chance to rule, without hearing from the opposing party, within eight hours of receiving the application, with dubious factual support for its order, and without providing any explanation for its order.”

Just cutting to the chase, the Supreme Court now appears to be holding the President and the federal government to the same standard of review as was being applied to the inadmissibles all these years — which admittedly is not much of a standard at all. Just declare the President and Attorney General no longer have the power to enforce the laws Congress enacted to make such determinations every other President and Attorney General was able to make without a hearing. What’s good for the goose is good for the gander, right? Cute.

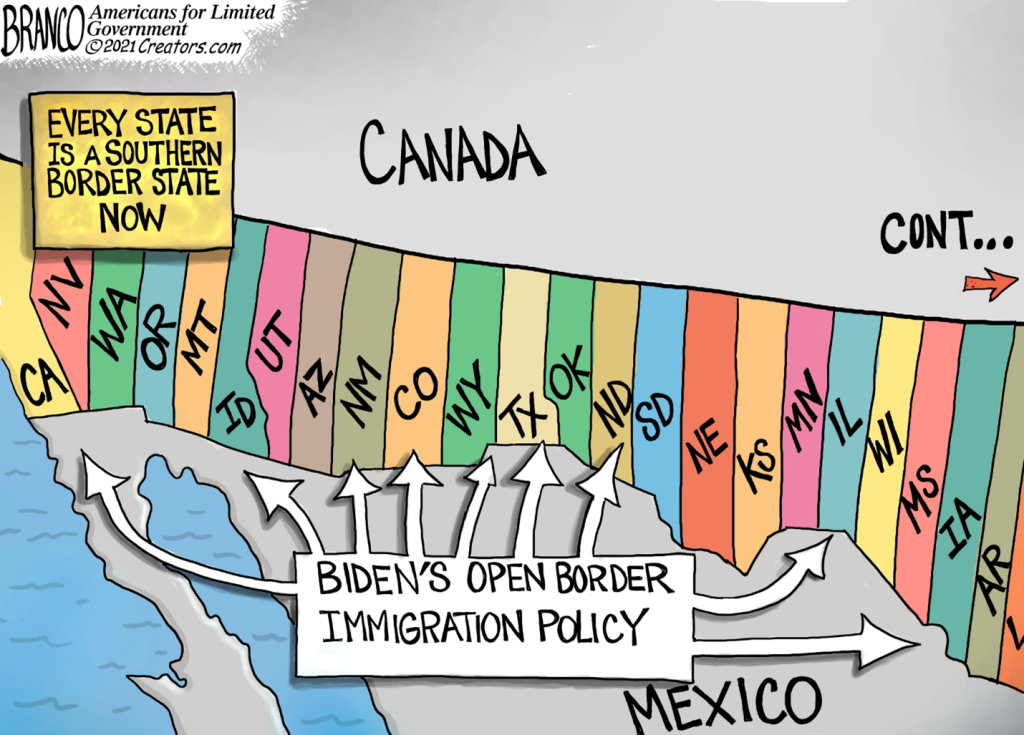

Here, the Supreme Court appears to be commandeering the enforcement of the border, who the executive branch determines to be a terrorist and who is therefore inadmissible into the U.S. The border is not unenforceable “until further order of this Court.” It’s a constitutional crisis. If the court is truly determined to have 15 million hearings for every illegal alien, maybe the President should just bring every one of the soon to be hundreds of thousands of detainees directly to the Supreme Court and see if they can handle it.

Robert Romano is the Executive Director of Americans for Limited Government Foundation.