Recently, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent was touting that the U.S. is expected to haul in some $500 billion of additional tariff revenue a year or more, stating, “I think we could be on our way well over half a trillion, maybe towards a trillion-dollar number. This administration, your administration, has made a meaningful dent in the budget deficit.”

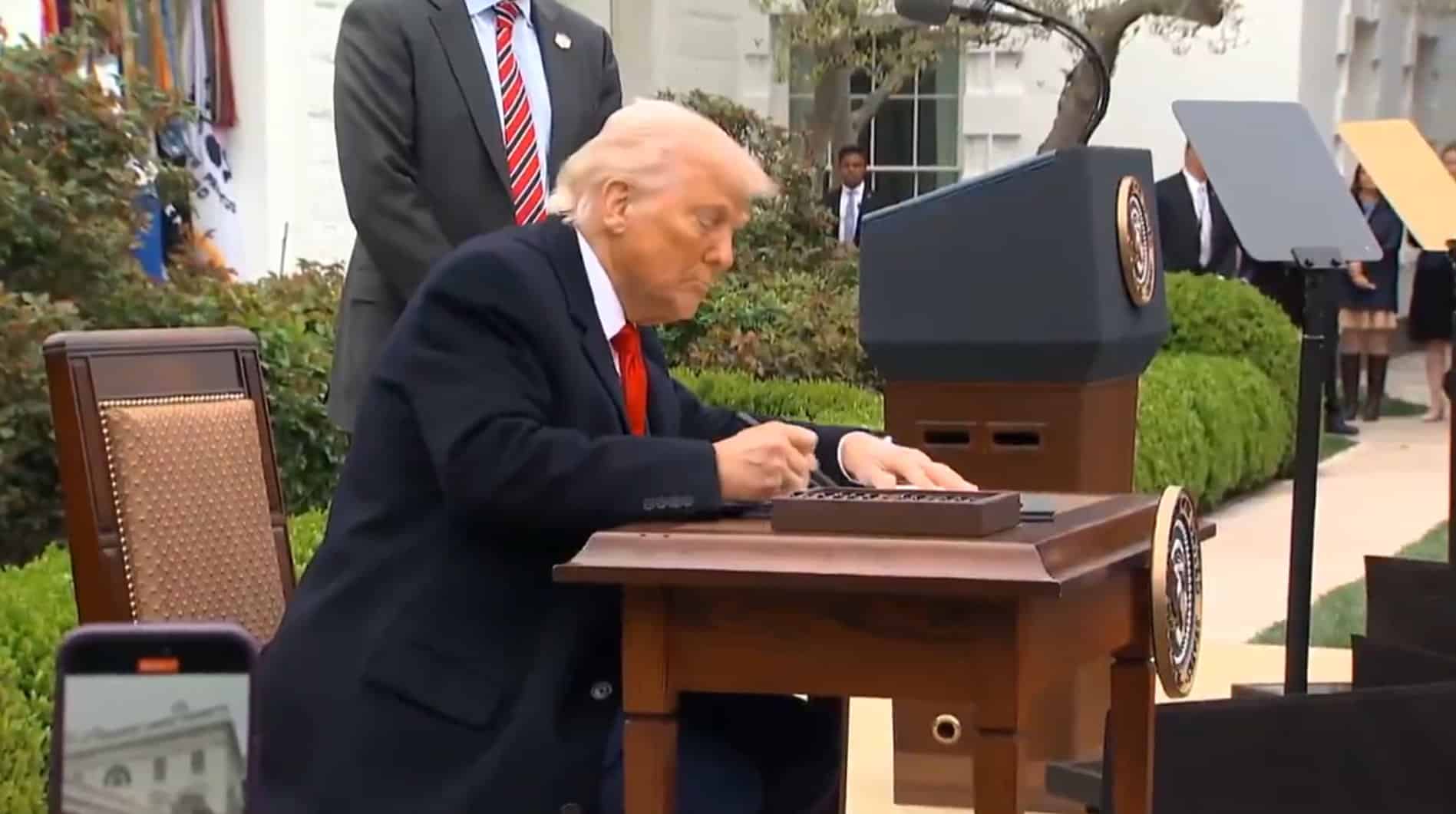

All thanks to President Donald Trump’s fair and reciprocal tariffs on imports globally since taking office that have already resulted in landmark trade deals reorienting the U.S. economic posture towards the world. And it’s the first meaningful deficit reduction at least since the budget sequestration of the 2010s.

But, maybe not, as federal courts meddle in the execution of President Trump’s foreign policy under Article II, the latest coming from the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals on Aug. 29 second-guessing the President’s emergency tariffs that Bessent was just saying can help raise $500 billion, upholding a May Court for International Trade decision.

Besides trade deficits, the other perhaps understated emergency is that of the rapidly climbing $37.4 trillion national debt as outlays continue outpacing revenues with close to $2 trillion deficits as far as the eye can see — until Trump’s tariffs came along.

That Congress has already delegated tariff authority to the president decades ago is not really the issue, but the question certainly being considered now might be by how much.

The tariffs were instituted under the National Emergencies Act and the International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

Originally the 1917 Trading With the Enemy Act, the law initially provided “That it shall be unlawful… [f]or any person in the United States, except with the license of the President, granted to such person, or to the enemy, or ally of enemy, as provided in this Act, to trade, or attempt to trade, either directly or indirectly… or is conducting or taking part in such trade, directly or indirectly, for, or on account of, or on behalf of, or for the benefit of, an enemy or ally of enemy.”

An enemy was defined as “any nation with which the United States is at war, or resident outside the United States and doing business within such territory, and any corporation incorporated within such territory”.

This was later expanded in 1933 by the Emergency Banking Act to include national emergencies: “During time of war or during any other period of national emergency declared by the President, the President may, through any agency that he may designate, or otherwise, investigate, regulate, or prohibit, under such rules and regulations as he may prescribe, by means of licenses or otherwise, any transactions in foreign exchange, transfers of credit between or payments by banking institutions as defined by the President…”

Over the years, these authorities have been used to place a variety of trade sanctions including embargos on North Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, Cuba, Russia, Iran, Venezuela and other adversary countries.

The Court for International trade in 1975’s Yoshida v. United States decision had even upheld Richard Nixon’s national emergency declaration in 1971 to impose 10 percent tariffs across the board to address the trade deficit. The court found back then: “We conclude, therefore, that Congress, in enacting § 5(b) of the TWEA, authorized the President, during an emergency, to exercise the delegated substantive power, i.e., to ‘regulate importation,’ by imposing an import duty surcharge…”

Since that time, Congress enacted the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act, which modified the Trading With the Enemy Act to remove the national emergency component but then reincorporate the national emergencies to 50 U.S. Code Sec. 1701: “Any authority granted to the President by section 1702 of this title may be exercised to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States, if the President declares a national emergency with respect to such threat.”

And the law included a very similar set of authorities under 50 U.S. Code Sec. 1702: “the President may, under such regulations as he may prescribe, by means of instructions, licenses, or otherwise… investigate, regulate, or prohibit… any transactions in foreign exchange, … transfers of credit or payments between, by, through, or to any banking institution, to the extent that such transfers or payments involve any interest of any foreign country or a national thereof, … the importing or exporting of currency or securities, by any person, or with respect to any property, subject to the jurisdiction of the United States…”

This provides for broad economic trade embargoes to be instituted by the President against hostile nations, more than just tariffs, including instituting sanctions and completely block all trade from a country.

President Trump is engaged in trade discussions with economies around the world, and the U.S. trade posture include the hundreds of billions of tariffs represents the President’s leverage in those discussions. The U.S. has already finalized trade deals with South Korea, Japan, the European Union, the United Kingdom, Philippines, Indonesia and Vietnam. Discussions are ongoing with China. All with the aim of protecting U.S. exports, opening up markets to goods abroad and for what does get imported, raise revenue.

This is central to the President’s conduct of foreign relations as the nation’s top diplomat under Article II of the Constitution.

The bonus is that if they remain in place, the tariffs will result in trillions of dollars of collections dramatically improving the U.S. fiscal outlook. Now the Supreme Court needs to take a look but the ones who really should be taking a look are Congress, which has already given the President broad trade authority in the event of emergencies. With so few things going right with the budget, the tariff revenue is definitely a pleasant surprise. Without these tariffs, we’re going to go bankrupt. Don’t stare a gift horse in the mouth.

Robert Romano is the Executive Director at Americans for Limited Government Foundation.