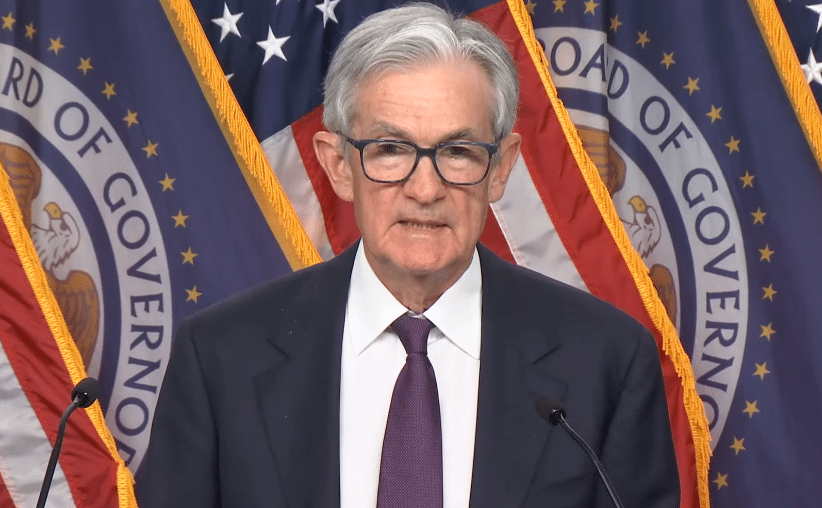

The U.S. Federal Reserve on Oct. 29 once again voted to cut the federal funds rate — from a range of 4.25 percent to 4 percent, to a range of 3.75 percent to 4 percent — as the central bank cited ongoing labor market concerns despite no official unemployment data for the month of September from the currently defunded Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

The Fed stated, “Uncertainty about the economic outlook remains elevated. The Committee is attentive to the risks to both sides of its dual mandate and judges that downside risks to employment rose in recent months.” That’s not great news. Fed rate cuts usually come closer to recessions.

But without the data being collected or reported during the government shutdown — BLS on an emergency basis published the September inflation report that showed a lower than expected 12-month total of 3 percent — it’s hard to say.

Usually, inflation slowing down corresponds with unemployment increasing, and this cycle has been no different. After inflation peaked at 9.1 percent in June 2022 and began slowing, unemployment has ticked upwards correspondingly from 5.7 million in January 2023 to almost 7.4 million in August, a 1.6 million increase.

So, maybe one month’s worth of data won’t make too much of a difference, whether it turns out to have been a big number of jobs lost or not in September. The Fed’s somewhat blind move to cut rates and stop asset sales appears prescient. With inflation slowing, the central bank is still anticipating labor market feedback as demand slows, which it has, with consumer credit briefly contracting at the beginning of 2025.

And this has been true with the other four rate cuts, three in 2024 and another last month.

What’s different this time is the Fed is also ending its cycle of quantitative tightening: “The Committee decided to conclude the reduction of its aggregate securities holdings on December 1.”

That’s significant. Since March 2022 when the Fed finally exited the Covid-era zero percent bound, quantitative easing cycle where it piled on trillions of dollars to its holdings, to fight inflation, now the central bank is strongly signaling that the worst is long since past us. After buying an additional $3.3 trillion treasuries and $1.3 trillion mortgage-backed securities — causing a massive price spike in housing, thanks, Jay! — during and after Covid, the Fed reverted to selling. Since early 2022, it then sold $1.56 trillion of treasuries and about $620 billion of mortgage-backed securities.

The Fed’s current balance sheet now shows $4.2 trillion of treasuries and about $2.1 trillion of mortgage-backed securities.

It also puts a further exclamation point on the massive tariff inflation that never materialized despite hyperventilating statements panicking in April when President Donald Trump announced reciprocal tariffs with the rest of the world. All the panic managed to do was make savvy investors wealthier.

But, again, without any forthcoming data — all hope is basically lost there will ever be any October reports for jobs, prices or much of anything else — it’s hard to say what the economy will look like by year’s end. By taking these steps amid the shutdown, the central bank might be hoping for the best, and preparing for the worst.

Robert Romano is the Executive Director of Americans for Limited Government Foundation.