For those who are hoping, for political purposes, that the U.S. economy will start tanking before the Nov. 2020 presidential election to make it more likely that President Donald Trump will be ousted in his reelection bid, you might want stop reading right now.

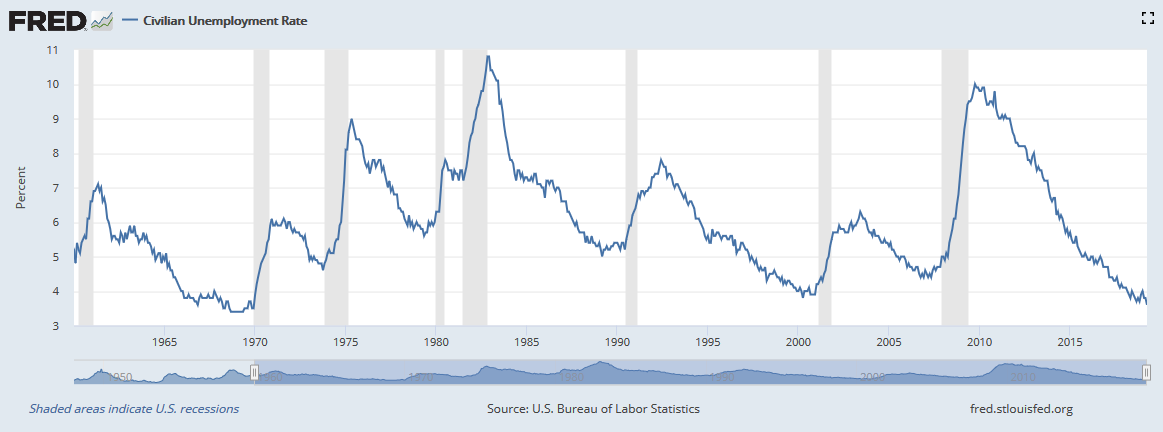

In April, the U.S. unemployment rate hit 3.6 percent, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the lowest since 1970, in what looks to be one of the best labor markets ever.

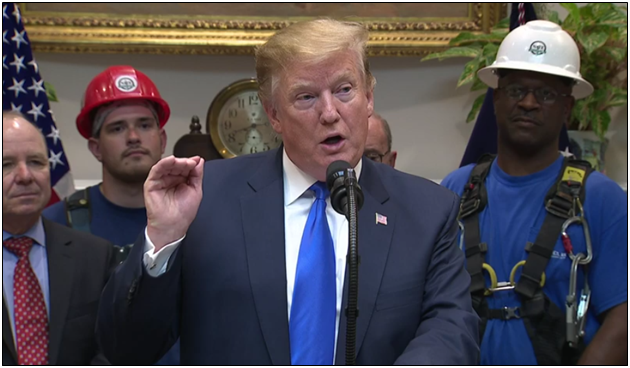

4.5 million jobs have been created since Trump took office in Jan. 2017 in the household survey, or 5.4 million in the establishment survey taken by employers.

Black, Hispanic and Asian unemployment remain at or near record lows.

The first quarter’s Gross Domestic Product for 2019 came in at an inflation-adjusted, annualized 3.2 percent.

That is, of course, all great news for the American people, and yet pretty bad news for Democrats who are running for office in 2020 against the incumbent Trump hoping a recession kicks in before Nov. 2020.

With a new low realized in this cycle — the prior low was 3.7 percent set in Sept. 2018 — the recession clock has been reset. Once peak employment has been reached for the first time in a business cycle, a recession comes on average about 11 months later, although in recent history that period has been as long as 16 months.

So, even if April 2019 was peak employment for this cycle — note, the jobless rate could still go lower, so we don’t know yet — but if it was peak employment, a recession might not begin until perhaps Sept. 2020, and it might not begin to show up in data until Oct. 2020 or so. Even then, unemployment might not start rising significantly until a couple of months into the recession.

Meaning, it would not really be realized until after the fact, and even then, the data would not likely have much of an impact on the election because it would take too long for it to be reflected across the body politic.

A couple of caveats. First, the labor participation rate dropped a lot in April, which explains a great deal of the reason why the unemployment rate dropped. Second, the household survey showed 100,000 fewer jobs, compared to the establishment survey which recorded 263,000 new jobs. Generally, in a growing economy, you want to see both labor participation and employment in the household survey increasing, so those numbers will bear watching in the coming months.

That said, even if this was peak employment, that means between now and when the data starts to move in the opposite direction — as is inevitable because of the cyclical nature of the economy — Trump will get to run on the strong economic numbers for the next many months as political attitudes for 2020 are setting in.

Perhaps for that very reason, from a position of economic strength, President Trump is moving to increase tariffs to 25 percent on $200 billion of goods against China even while negotiations for a new trade deal with Beijing are ongoing.

On May 5, on Twitter, the President announced, “For 10 months, China has been paying Tariffs to the USA of 25% on 50 Billion Dollars of High Tech, and 10% on 200 Billion Dollars of other goods. These payments are partially responsible for our great economic results. The 10% will go up to 25% on Friday. 325 Billions Dollars… of additional goods sent to us by China remain untaxed, but will be shortly, at a rate of 25%. The Tariffs paid to the USA have had little impact on product cost, mostly borne by China. The Trade Deal with China continues, but too slowly, as they attempt to renegotiate. No!”

For the trade talks, the signal to China is clear. The longer they wait to make a deal, the higher the tariffs will go.

Also, do not discount the fact that on May 4, North Korea conducted a new missile test. Raising the tariff sends a direct message to China that good trade relations also depend on stability in the region. Now, the possibility of lowering the tariffs becomes a steeper climb for Beijing to cure both North Korea and the trade balance.

On trade, Trump is taking a proactive stance as he promised when he ran in 2016. The trade in goods deficit with China hit a record high in 2018 at $419.1 billion according to the U.S. Census Bureau in the same year President Donald Trump levied the initial 10 percent tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods shipped to the U.S., which in turn came atop a 25 percent tariff on the $50 billion of goods from China.

In 2017, the deficit was $375.6 billion. So, it increased by $43.5 billion. But for the tariffs, Trump can now argue, and the trade deficit might be much bigger and economic growth that much slower. There wouldn’t be as many jobs coming back to the U.S.

Undoubtedly, if the GDP and jobs numbers were moving in the opposite direction of where they are now, Trump’s opponents would undoubtedly be leveling the blame at his policies. Therefore, when the numbers are moving in the right direction, Trump will rightly claim his share of the credit. And with 2020 rapidly approaching, the President could not ask for a better recipe.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.