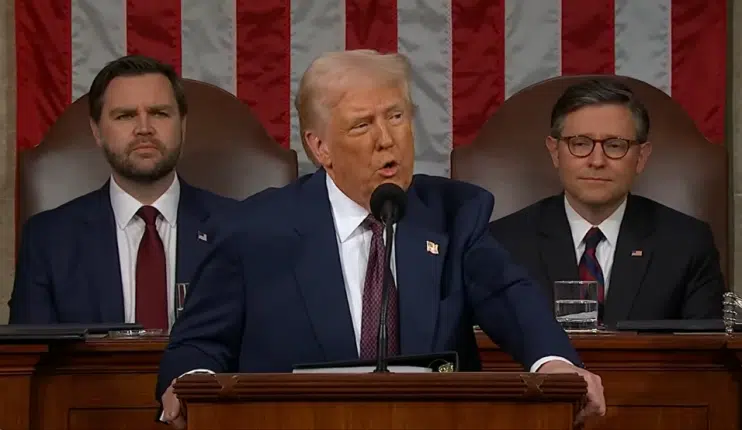

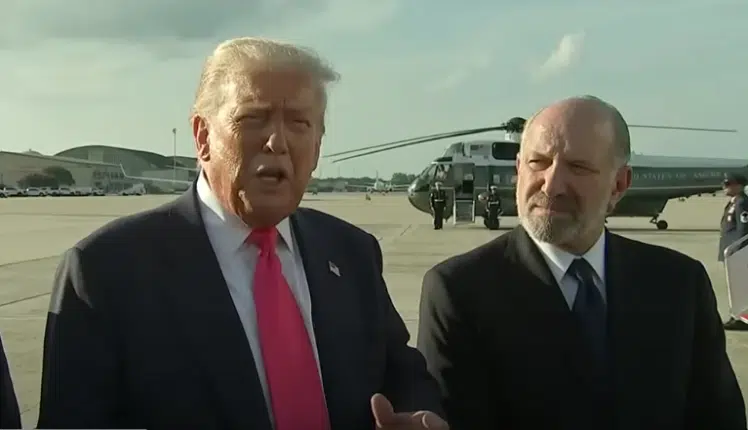

Treasury yields flashed warning signs again with intraday inversions of the 10-year and 2-year treasuries as President Donald Trump blasted the Federal Reserve once again for acting too slowly to lower interest rates.

“Germany sells 30 year bonds offering negative yields. Germany competes with the USA. Our Federal Reserve does not allow us to do what we must do. They put us at a disadvantage against our competition. Strong Dollar, No Inflation! They move like quicksand. Fight or go home!” Trump tweeted on Aug. 22.

Here, Trump is referring to overseas government bonds, such as Germany and Japan, that are both trading in negative territory at the moment. He has previously called for the central bank to lower its key interest rate 1 percentage point to a range of 1 percent to 1.25 percent. Although not quite negative, it would be getting close.

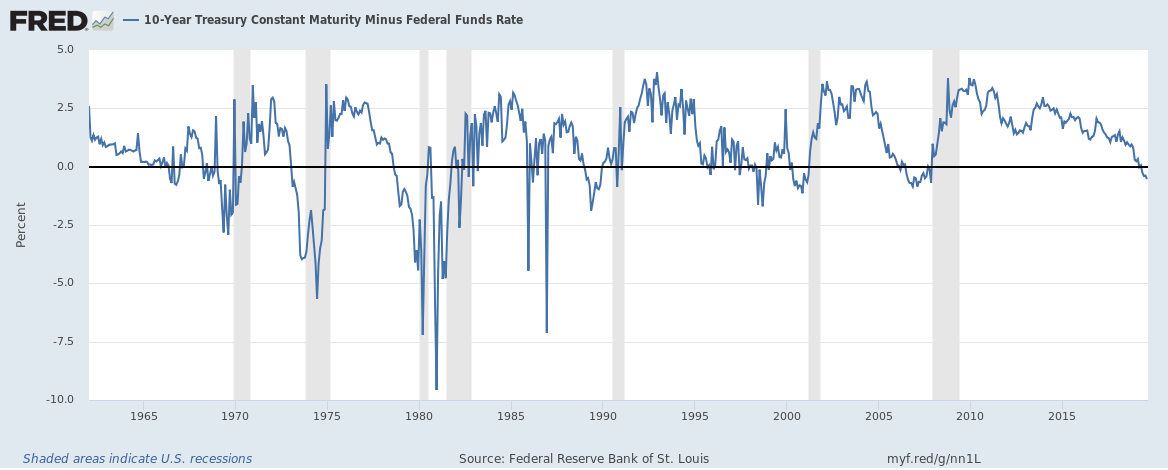

Trump is not wrong. Relative to other countries, interest rates in the U.S., as low as they currently are, are higher than those of trading partners. And the federal funds rate at 2 percent to 2.25 percent is well above the 10-year treasury and have been inverted since May and so has the 10-year, 3-month treasuries spread. In the meantime, the U.S. dollar versus the Chinese yuan and the euro remains quite strong, making exports to the U.S. much cheaper.

But even if it started aggressively cutting rates right now, can the Fed really do much about it? We were at near-zero percent on the federal funds rate and did trillions of dollars of quantitative easing during the Obama administration and yet, growth was still tepid as we lost market share to China. The Fed supposedly runs monetary policy but exchange rates is not something it appears to focus on. It probably should.

As for Trump’s comparison to Germany and Japan, negative rates are not a positive economic indicator. Just as high interest rates signal inflationary environments, negative rates occur in deflationary environments, with slow or no growth. If rates are about to go negative, then Trump is absolutely right, the dollar is too strong relative to other currencies.

Whether the Fed could weaken the dollar sufficiently with interest rates cuts and open market operations to cure overseas competitive devaluations is a really great question. But I don’t think so. I think that when it comes to the dollar being too strong, the Fed is basically out of ammunition. That’s something we need to work out via diplomacy and some sort of international monetary accord, perhaps as part of a trade agreement such as the one currently being negotiated with Beijing. I have suggested barring currency manipulators like China from treasuries markets as a potential penalty, but such a drastic move carries a lot of risk in terms of disrupting financial markets and would carry further repercussions in terms of U.S.-Chinese relations.

The conundrum is this: How do you weaken the dollar when it’s the world’s reserve currency and everyone piles it up like it’s gold, and what’s more, everyone has an incentive to do so because it makes their exports cheaper?

That said, I understand and appreciate the President’s frustration with the Fed. When it comes to economic conditions, arguably, because the Fed waited so long to hike rates from its near-zero percent levels after the financial crisis and Great Recession — the first hike did not come until Dec. 2015 and the full normalization not until after the 2020 elections beginning in Dec. 2016 — it has very little room to maneuver for the next recession.

If the Fed had hiked rates sooner, say starting in 2014 and 2015, it seems likely the recession would have already occurred. Were the rate hikes forestalled until after the 2016 election? Was it politically timed to help the incumbent party at the time? I think those are fair questions.

Either way, with so little room left to maneuver, we’re in zero-bound territory and we could be about to test negative interest rates in the next recession when it does come, and all of the perverse incentives they might create as borrowers including governments get paid interest to borrow at negative rates.

And in terms of rate cutting, the Fed waited until after its own rate had inverted with the 10-year treasury, finally moving rates down on July 31, but not by enough to cure the inversion. Now, whether those inversions could have been avoided is an interesting proposition. Hypothetically, it could have eased earlier this year.

In fact, Trump has been pointing to the relatively higher interest rates since Oct. 2018, when he told the Wall Street Journal, “I’m very unhappy with the Fed, because Obama had zero interest rates and I have almost normalized—and maybe normalized, depending on who you’re talking to—interest rates. You give me zero interest rates and you show me my numbers with zero interest rates.” Was the President ahead of the curve?

Leaving that aside, in theory, the Fed could cure its own interest rate inversion now by dropping its rate toward zero, but it’s worth noting that the Fed tends to ease as we get closer to recessions and that it cures its inversion as we enter the recession. It might want to see the 10-year, 2-year fully invert before it fully moves in that direction. Meaning, once the Fed cures its inversion, that may not be a really good signal.

So maybe the President should be careful what he wishes for. On the other hand, could doing the Fed ending its own inversion now help avert a recession? It’s easy to see why the President would be concerned.

Now, there is some talk that, somehow, interest rate inversions, which occur like clockwork prior to recessions, were themselves the cause and not merely a prediction of a recession, that they become some sort of self-fulfilling prophecy. I don’t buy into that since every recession in recent history you can look at included some inversions as a flight to safety occurred, and business cycles being what they are, nothing lasts forever.

Either way, it is clear that we are nearing the end of the business cycle. Right now, the economy is strong, coming off its strongest growth since 2005 and a record low 3.7 percent unemployment rate. Once the 10-year, 2-year fully inverts, you might expect a recession about 16 months later on average, which might put it in Dec. 2020 if it were to happen right now, after the election, if that’s what you’re wondering about.

But it could be sooner. If so, a good question might be whether the central bank timed its own rate hiking after the 2016 election so that a recession would occur just as voters were headed to the polls in Nov. 2020. Were they out to get Trump? We’ll find out soon enough. Stay tuned.

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.