ALG Editor’s Note: In the following featured blog posting at FT Alphaville, Morgan Stanley’s Arnaud Marès notes that “The question is not whether [governments] will renege on their promises, but rather upon which of their promises they will renege, and what form this default will take”:

Ask Not Whether Governments Will Default, but How

By Neil Hume

That’s the rather worrying title of a fresh report, published on Wednesday by Morgan Stanley, that unsurprisingly raised a few eyebrows in City of London dealing rooms.

Its author Arnaud Marès says it is not a question of when governments renege on their promises, but of who suffers. And the answer to that question is the one constituency that has come through the Great Recession virtually unscathed — senior unsecured bondholders.

Actually that’s not precisely true, as the old will suffer as well.

Here’s a couple of snippets from the report:

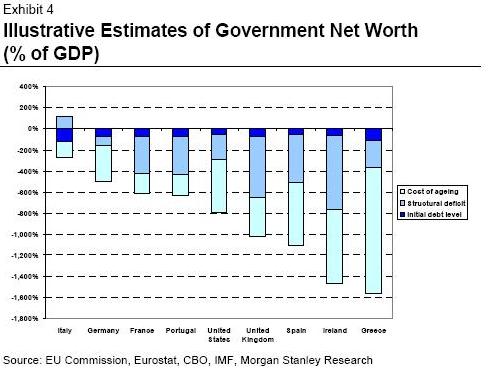

Debt/GDP ratios are too backward-looking and considerably underestimate the fiscal challenge faced by advanced economies’ governments. On the basis of current policies, most governments are deep in negative equity.

This means governments will impose a loss on some of their stakeholders, in our view. The question is not whether they will renege on their promises, but rather upon which of their promises they will renege, and what form this default will take.

Marès reckons it will take the form financial oppression:

Financial oppression as an alternative to outright default. Outright default is not the only way to impose losses on creditors. Financial oppression – the fact of imposing on creditors real rates of return that are negative or artificially low – can take other forms: repaying debt in devalued money (e.g., through unanticipated inflation), taxation or regulatory incentives on institutions to purchase government debt at uneconomic prices, for instance (see also “Default or Inflate or…”, The Global Monetary Analyst, February 24, 2010). Repaying debt in devalued money is particularly effective when the initial stock of debt is high – as it is now. Distorting prices in the government’s favour is particularly effective when the financing requirement is high – also a situation we face now and for years to come.

And if you’re thinking that’s happened many times before, you’re right.

Financial oppression has taken place in the past as an alternative to default in countries that are generally considered to have a spotless sovereign credit record. Examples include: the revocation of gold clauses in bond contracts by the Roosevelt administration in 1934; the experience by then Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton of issuing perpetual debt at an artificially low yield of 2.5% in the UK in 1946-47; and post-war inflationary episodes, notably in France (post both world wars), in the UK and in the US (post World War II). Each took place at a time when conflicting demands on finite government resources were high, and rentiers wielded reduced political power.

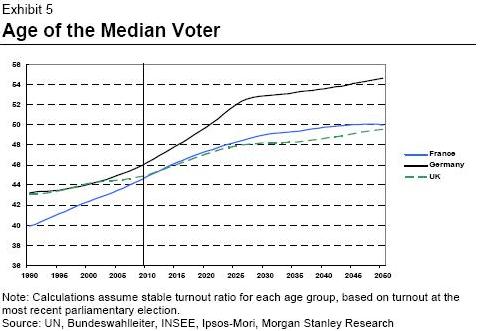

Exhibit 5 shows the rapid increase in the age of the median voter in large western European countries. In principle, having governments and policies shaped by older voters ought to be favourable to bond holders, because bonds are more likely to be held by the old than the young and policies that would harm bond holders would often also harm the old (inflation for instance redistributes wealth from the old to the young). The first problem with this argument is that the constituency of the elderly is also the biggest competitor to bond holders because of the considerable size of the direct claim it has on the government balance sheet in the form of pensions, social security and health insurance, etc. The more reluctant they are to relinquish these claims, the higher the risk for bond holders. The second problem is the dilution of bond ownership, which results in lesser alignment of the interest of bond holders with older voters: even in the UK, where the domestic and pension industry has traditionally dominated the gilt market, its ownership of gilts has decreased in recent years from around 60% to 40% of the market (excluding Bank of England purchases), to the benefit of foreign investors.

More on this subject in the usual place.