In Greek mythology, Cassandra was granted the gift of prophecy by Apollo, but because she refused to be his consort, the god punished her by making it so that nobody would believe her predictions.

Today, it appears that credit rating agencies have contracted a Cassandra syndrome. They have warned profligate nations, like Greece, Ireland, and the U.S., until they are blue in the face that they are spending too much. That their national debts are unsustainable. That unless drastic actions are taken to rein in unsustainable spending, dire consequences will follow.

Alas, the governments are not listening. They do not believe the Cassandra agencies.

Ireland is a perfect example where half measures have made little difference in the nation’s fiscal outlook. Despite receiving praise when budget cuts were proposed over a year ago, the Irish government has largely not followed through with them. Its recent credit rating downgrade by S&P directly reflects the less-than-adequate cuts that have been made.

At the time, Ireland complained that S&P’s downgrade had used an “extreme estimate” to calculate the size of its bank bailout. But, since then, Ireland has had to revise upward its estimate for recapitalizing Anglo-Irish Bank, now at €50 billion, as reported by the Wall Street Journal.

This open-ended commitment amounts to bank losses being poured atop public debt. Fine Gael estimates that the bank bailouts in Ireland will eventually double the national debt. It is likely that the nation’s debt will continue to grow to over 100 percent of GDP before the decade ends.

The budget situation overall has not improved much. After its budget peaked at €56.082 billion gross expenditures in 2008, Ireland has only cut down to a proposed €54.940 billion in 2010. It foresees keeping that level of spending indefinitely.

The nation’s public pension system is largely considered to be one of its greatest accrued liabilities, at over €129 billion. But the only reforms to the public pension system thus far put forth in the 2010 budget are token ones: raising the retirement age to 66 from 65; and imposing a maximum retirement age of 70; pensions will be derived from a career average instead of final salary; and they’re considering using their Consumer Price Index to calculate post-retirement increases.

The effect has been negligible. Ireland, despite all of its rhetoric of reforming the broken pension system, remains committed to a defined benefit scheme — even for new entrants. Overall, it has only cut about €1.2 billion from the budget, but its deficit is €13.718 billion. It foresees higher deficits until 2012.

Even then, the government only expects the deficit to drop because it thinks the economy will recover and revenues will rise, not because spending would be cut. In fact, overall spending won’t be cut significantly in any upcoming budgets.

Overall, Ireland’s debt has risen from a 25 percent share of GDP at the end of 2007 to 64.5 percent of its GDP at the end of 2009 at €75.2 billion.

All told, because it has done little more than freeze spending, and on top of that committed to a tremendous bank bailout, Ireland is still facing a worsening Greece-like crisis. Unfortunately, Ireland has not managed to substantially reduce its debt-and-deficit-to-GDP ratios.

This should be instructive across the pond here in Washington.

As the U.S. considers the preliminary findings of Barack Obama’s National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, it would do well to consider the Irish example, and consider listening to the Cassandra credit agencies. Moody’s has warned the U.S. that if interest owed on the national debt rises to 18 to 20 percent of revenue, that our credit rating would be downgraded. As noted by Investor’s Business Daily, that will be reached 2018 based on Congressional Budget Office estimates.

The deficit commission will do little to prevent that from happening, only proposing cutting about $15 billion a year in interest payments by 2018, which would still rise to $696 billion that year. That’s still above 18 percent of the revenue the CBO projects that year, $3.83 trillion. This means that either the commission did not consider Moody’s warning, which would be alarming, or they did consider it, but are okay with the credit rating being downgraded.

It gets worse. The commission will do nothing to balance the budget any time soon. In fact, it does not foresee a balanced budget until 2040. Frankly, we don’t have thirty years to balance the budget.

Year-on-end, the $13.7 trillion debt would continue to grow under the commission’s proposal, surpassing 100 percent of GDP in just a few short years. To finance the debt, the Federal Reserve will print hundreds of billions of dollars, making it the top lender to the U.S. sometime in the not-so-distant future in 2011.

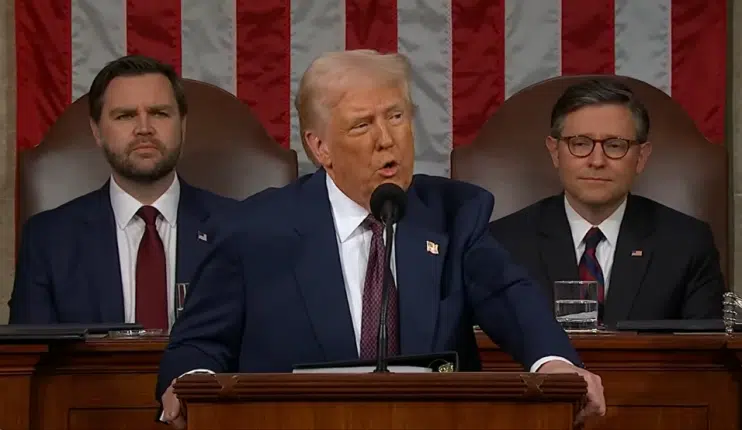

First and foremost, newly elected congressional Republicans must be committed to avoiding an Irish-like crisis. In order to do so, they must heed the warnings of the Cassandra credit rating agencies, before it is too late. That means when they present their budget proposal, it must take into account what Moody’s has warned, and then tailor their proposal to avoiding the calamity prophesized.

Bill Wilson is the President of Americans for Limited Government.