Instead of playing defense against green pressure groups that peddle dubious allegations, private companies should follow the lead of Chevron Corp., which has pushed back aggressively against the plaintiffs’ attorneys in case that involves pollution allegations in Ecuador. Chevron has presented evidence that shows a court appointed expert may have been operating in collusion with the litigants. Moreover, the company claims a concerted effort has been made to manufacture environmental claims, deceive public officials and to inflate liability costs.

Chevron has filed a civil lawsuit under the Racketeer Influence and Corruption Organizations Act (RICO) against the trail lawyers and consultants who stand to benefit from ongoing environmental litigation. The plaintiffs include residents of Ecuador’s Amazon rain forest who have long sought to hold Chevron responsible for environmental damage they claim was caused by Texaco, which had operations in the country from 1965 to 1992. Chevron assumed the potential liabilities when it acquired Texaco in 2001.

In February, a judge in Ecuador ruled that Chevron must pay $8.6 billion to clean up oil pollution in Ecuador’s rain forest. But the plaintiffs have experienced setbacks in U.S. courts and earlier this month a panel of international arbitrators in The Hague issued a preliminary injunction that could work against any effort to enforce the judgment.

Chevron intends to appeal the decision and has issued the following statement:

“The Ecuadorian court’s judgment is illegitimate and unenforceable. It is the product of fraud and is contrary to the legitimate scientific evidence. Chevron will appeal this decision in Ecuador and intends to see that justice prevails. The United States and international tribunals have already taken steps to bar enforcement of the Ecuadorian ruling…Chevron intends to see that the perpetrators of this fraud are held accountable for their misconduct.”

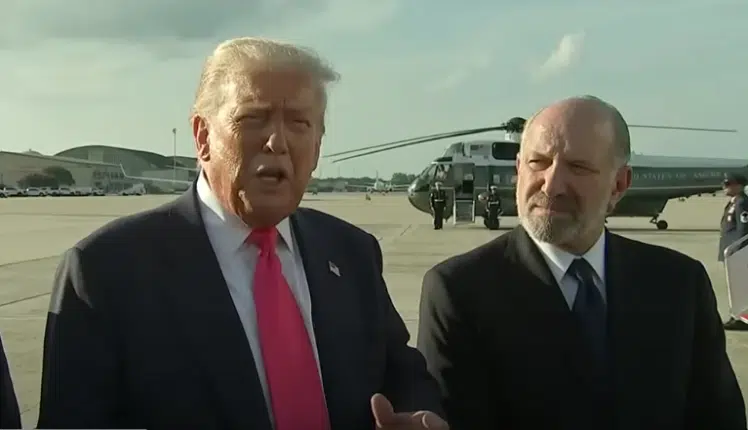

Cheveron’s RICO suit alleges that the defendants and key co-conspirators have used the lawsuit to threaten the company, dupe U.S. government officials and harass Chevron employees. Those named in the suit include: New York City-based plaintiffs’ lawyer Steven Donziger; his Ecuadorian colleagues Pablo Fajardo and Luis Yanza; their front organizations, the Amazon Defense Front and Selva Viva; and Stratus Consulting, a Boulder, Colo.-based consulting firm.

Donziger, the New York attorney, has stepped down as the lead attorney and has declined to make any recent media comments. The plaintiffs have reacted to recent developments through Pablo Fajardo, an attorney in Ecuador.

Most recently, Judge Lewis Kaplan of the Southern District of New York, issued a preliminary injunction order against RICO defendants. The order “enjoins and restrains” the defendants from receiving any benefits, directly or indirectly, until after a final determination is made about the RICO suit.

The Chevron case is the subject of a new film called “Crude,” which focuses attention on the evidence company officials have presented in their RICO suit. Industry officials who are constantly under attack from well-heeled environmental interests should carefully study the example set by Chevron. The company did not retreat and surrender even when it was seemingly easy to settle. Consequently, green activists who are accustomed to rolling over private companies have been forced to play defense in the court room. When it filed the RICO suit, Chevron also made its case to the public in a press release that explored key aspects of its case against the defendants.

“Documents, sworn deposition testimony, and outtakes from the movie Crude showing Donziger and his environmental consultants, including Stratus Consulting, plotting to secretly write the report of the supposedly `neutral’ Ecuadorian court expert—Richard Stalin Cabrera Vega—who was appointed at the plaintiffs’ lawyers’ insistence to serve as the Lago Agrio court’s sole, “global damages expert.” The ghostwritten ‘Cabrera’ report would serve as the basis for the plaintiffs’ lawyers’ demands for more than $27 billion in damages—a figure that later was inflated to more than $113 billion after evidence of the Cabrera fraud emerged.

Documents and e-mails demonstrating that, after ghostwriting Cabrera’s initial report recommending more than $16 billion in damages, Donziger, Stratus and their co-conspirators pretended to criticize “Cabrera’s” report and demand that the damages be increased. The conspirators then prepared “Cabrera’s” responses to their own criticisms, increasing the initial damages estimate by more than $10 billion. The scheme culminated in a fraudulent “peer review” conducted by Stratus staff in which they pretended to perform an “independent” review and validation of the reports that they had ghostwritten for Cabrera’s signature.

* Plaintiffs’ documents, including Donziger’s own detailed notes, as well as outtakes from Crude revealing a campaign of judicial intimidation by Donziger and his colleagues. On film, Donziger declared, “the only language that I believe, this judge is gonna understand is one of pressure, intimidation and humiliation. And that’s what we’re doin’ today. We’re gonna let him know what time it is . . . . We’re going to scare the judge, I think today.” These tactics were employed because, according to Donziger, judges in Ecuador “make decisions based on who they fear the most, not based on what laws should dictate.” When it was suggested to Donziger that no judge would rule against them because “[h]e’ll be killed,” Donziger replied that, though the judge might not actually be killed, “he thinks he will be… Which is just as good.”

* Evidence of a concerted effort by the named defendants and others conspiring with them to deceive members of the U.S. Congress, U.S. and state government regulatory agencies, and others into believing that the company faces a multibillion-dollar liability and has sought to mislead investors-all with the aim of forcing Chevron to settle. The campaign has included demands for Securities and Exchange Commission investigations, lobbying of government officials, including the U.S. Department of Justice and New York Attorney General, direct targeting of others with misinformation, and overt threats directed at Chevron’s Board of Directors.

* Correspondence, memos, emails and agreements documenting the financing of the fraudulent scheme and the planned division of the windfall. The evidence reveals that the real parties standing to gain from the Lago Agrio lawsuit are U.S. law firms and investors, not indigenous rainforest residents. These U.S lawyers have also schemed to divvy up the proceeds of any recovery they extract from Chevron outside of Ecuador and beyond the reach of Ecuadorian law.”