By Bill Wilson — Markets were awash with irrational exuberance on Nov. 30 upon an announcement by the Federal Reserve and other central banks to lower interest rates for “temporary U.S. dollar liquidity swap arrangements”. Particularly, this will lower the cost of dollars in Europe, which is thought will help with any potential liquidity shortfalls there.

Whether that will work or not remains to be seen. These facilities were already open, so it is unclear how lowering the cost of dollars by a half-a-percentage point of interest — a liquidity booster — will do anything to solve Europe’s inherent solvency crisis.

Nonetheless, the markets’ response — the Dow surged by 490 points — indicates that there is a big appetite for more credit expansion by central banks. They would really like to see more quantitative easing from the Fed, and in particular the European Central Bank, to bail out European banks that bet poorly on sovereign debt.

All of which raises the question: Is more debt good for the economy? Will this make us wealthier?

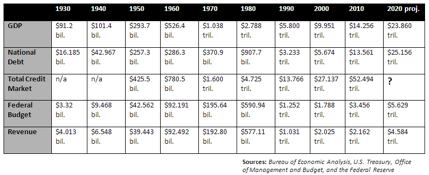

Since 1940, with few exceptions, the economy has roughly doubled nominally in size, along with the federal budget, revenues, the national debt, and the total outstanding credit nationwide. It has happened like clockwork, and if government projections are to be believed, will happen again this decade.

By 2020, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) projects the GDP to grow from its current level of about $15 trillion to more than $23.86 trillion. It shows the budget growing from its current $3.7 trillion level to $5.629 trillion, revenues from $2.2 trillion to $4.584 trillion, and the national debt from $15 trillion to $25.156 trillion.

Certainly, there is a long set of data to confirm that view, as shown in the following table, where routinely, each category roughly doubled every decade.

However, there are exceptions. For example, the 2000’s were the first decade since the 1930’s wherein revenues did not about double. Instead, they moved from $2.025 trillion in 2000 to $2.162 trillion in 2010.

This was in large part due to the financial crisis and the recession that followed. Revenues had reached a high of $2.56 trillion in 2007 when the deficit was only $160.7 billion, but then collapsed along with the economy.

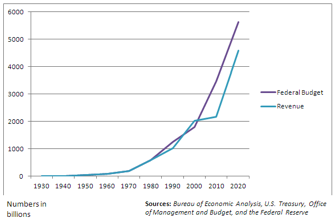

The recession has not slowed down government spending, however. To cope with the economic downturn, Keynesian central planners in Congress and the Fed brought forth an unprecedented explosion of government borrowing and monetary expansion, totaling trillions. While revenues are down by roughly $400 billion since the downturn began, spending has jumped by about $1 trillion. As a result, the budget deficit now totals $1.4 trillion.

This is shown visually in the following chart, and shows the trillion-dollar annual deficits the federal government is planning to run over the next ten years.

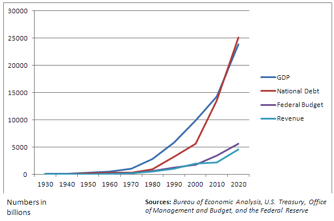

But, a spiking of the deficits was not the only side effect of the recession. Now, the national debt is poised to become larger than the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) this year if not early next year. Right now, the debt is currently rising by about 10 percent on annualized basis, while the economy is only tepidly growing at about 2 percent.

And if nothing changes about the budget baseline, the debt will continue growing at about 6.6 percent every year this decade, as shown below. Even if the economy were to grow vigorously as OMB anticipates, the growth of the debt will far outpace it.

That could make surpassing the 100 percent debt-to-GDP mark a permanent fixture for taxpayers — a point of no return if spending and borrowing is not brought under control and the economy fails to recover robustly.

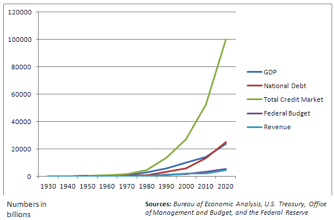

But even that does not show the entire picture. The final data point we look at is total outstanding credit in the nation, which according to the Federal Reserve currently totals $52.554 trillion. Like all of the other indicators, this is one that has roughly doubled every single decade.

Moreover, because money is created through the lending process, according to the Keynesians who have run the economy for much the past century, it is a figure that must always grow in order for there to be any economic expansion.

Here, it is shown growing to roughly $100 trillion by decade’s end, presumably to support the projected $23.86 trillion GDP by 2020. So the thinking goes, it has doubled like clockwork every decade before, so why not again?

There are a few problems with this outlook. First, as revealed by economic analyst Chris Martenson, total outstanding credit is not growing at a pace to double this decade. Not even close.

In fact, it has been completely flat since 2008 according to Fed data, owing in large part to declining home values, the high rate of foreclosures, and an unwillingness on the part of the American people to increase their debt exposure.

We have already maxed out our credit cards. Families are still deleveraging from the credit bubble to improve their household budgets.

All of which means we have hit a natural ceiling, at least for now, for credit expansion. So addicted to debt are we, as credit fails to grow substantially in the next decade, it is likely that OMB’s rosy economic outlook will prove to be very wrong. That in turn will mean revenues are actually much lower and the debt much higher.

Too much debt, which has been used for decades to juice the economy, has now become a major drain on economic output.

There is another major problem. Note how it takes an ever-widening gap between total credit and economic growth, supposedly to support that growth. That indicates there is less bang for the buck when it comes to expanding credit, resulting in exponentially higher borrowing by the entire economy but with smaller amounts of growth in return.

In short, all we are accomplishing presently is creating debt, not wealth. And one day in the not too distant future, the bill will come due.

Bill Wilson is the President of Americans for Limited Government. You can follow Bill on Twitter at @BillWilsonALG.