So far it’s not much, several billion in stock buys by central banks. But all over the world, there are about $10.2 trillion of foreign exchange reserves that could be tapped, according to the International Monetary Fund’s Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) database.

Interestingly, the IMF notes that “COFER data for individual countries are strictly confidential.” So, when central banks flood equities markets with excess reserves, investors likely won’t know until after the fact, and then, only if such purchases are disclosed.

But why would central banks purchase stocks? Aren’t those… risky?

In 2000, none other than current Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke — then a professor — commenting on Japanese policies after their housing bubble popped in 1989, included corporate bond and equity purchases in his menu of options that might be pursued in an environment with near-zero interest rates.

Bernanke left no mistake that the reason to boost aggregate demand in this fashion is to raise prices: “The object of such purchases would be to raise asset prices, which in turn would stimulate spending”.

Vince Reinhart, then Fed Director of its Division of Monetary Affairs, at Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting in June 2004 described the circumstances under which a central bank might engage in such purchases: “if the policymakers believed that deflationary forces were severe.”

Reinhart also dismissed the possibility at the time, saying, “These options would change how we are viewed in financial markets, involve credit judgments of a form we are not used to, perhaps smack of desperation, and pull us into a tighter relationship with other parts of government.”

But let’s leave that aside. Consider carefully the circumstances Reinhart outlined when this might actually happen: “if the policymakers believed that deflationary forces were severe.” Uh-oh.

Now that central banks are actively buying stocks, this could be an extremely bearish signal for investors. Central banks may not believe that the current market rally is sustainable and that the means to propping it up is to step in and forcefully monetize the markets.

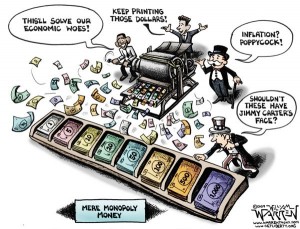

That alone would be outrageous enough, if the object is to socialize risks in the private sector, and to artificially bolster the capital gains of a select few. But let’s examine some numbers to see what the impact might be if central banks let loose their $10.2 trillion of foreign exchange reserves on the stock market.

According to the World Federation of Exchanges (WFE), the total value of equities worldwide fell from a high of $56.8 trillion in May 2008 to $42.9 trillion in Sept. 2008. By the end of 2008 it was $32.8 trillion. And in Feb. 2009, it had dropped to a low of $29.1 trillion.

In less than a year, over $27.7 trillion of wealth was erased.

Since that time, there has been a considerable recovery. The total value of equities rose to $54 trillion in 2010, and then came down slightly in 2011 to $47 trillion, with the WFE citing collateral damage from the sovereign debt crisis.

In Jan., it stood at about $50.8 trillion. So, global equity markets are currently about 74.5 percent off their lows and climbing. To look at it from the perspective of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, it hit a low of 6594 in March 2009, and has risen to about 13000 today. It’s nearly 100 percent off its low.

Does that mean it is time for a correction? Or even a cyclical recession?

For certain, central banks stepping into stocks now will be buying the market at or near a high. Why would they do that unless “policymakers believed that deflationary forces were severe”?

Perhaps that is just a pretext. One effect of central banks buying at a high would be to allow favored shareholders of companies to realize profits on their stock holdings (i.e. capital gains). It’s important to note that the high percentage gains in equity values over the past three years were actually a low-volume trade.

In other words, not too many people appear to be buying the Dow at 13000.

Are financial institutions sitting on a lot of overvalued assets and need to sell them to book the gains before the correction comes? Hmmm.

There’s over $20 trillion of gains at stake since the markets’ collective lows of 2009. But don’t expect a bailout in your personal portfolio solely from central banks’ foreign exchange reserves. There are not enough of those to buy all of the world’s stocks.

So, the privileged few will get a bailout — and a preemptive one at that. And the worst part is there will be no way to stop the intervention.

Outraged yet? You should be. But then, this is what happens when value is completely severed from currency. It is time to seriously reconsider this Monopoly money scheme.

Bill Wilson is the President of Americans for Limited Government. You can follow Bill on Twitter at @BillWilsonALG.