An Americans for Limited Government review of Internal Revenue Service (IRS) revenue procedures has revealed that the Determinations Unit responsible for targeting tea party and other groups applying for tax-exempt status was required to send certain applications to the Exempt Organizations (EO) Technical office based in Washington, D.C. for special scrutiny.

This would belie initial claims made by former IRS Commissioner Steven Miller to congressional investigators that the scandal had been originated by two “rogue” officials at the Cincinnati office.

The criteria used in 2010 for identifying special cases reads: “EO Determinations will refer to EO Technical those applications that present issues which are not specifically covered by statute or regulations, or by a ruling, opinion, or court decision published in the Internal Revenue Bulletin.”

The rule continues, “In addition, EO Determinations will refer those applications that have been specifically reserved by revenue procedure or by other official Service instructions for handling by EO Technical for purposes of establishing uniformity or centralized control of designated categories of cases.”

One key question that emerges from the rule is who created the “designated category of cases.” Did the Determinations Unite receive “other official Service instructions” to designate these cases? Did they just take it upon themselves? Did EO Technical tell them to do it?

In his testimony, outgoing IRS commissioner Miller suggested in his May 17 testimony that “People in Cincinnati decided let’s start grouping these cases, let’s centralize these cases.”

Except, under the procedure, the “centralized control of designated categories of cases” is limited to cases “specifically reserved by revenue procedure or by other official Service instructions for handling by EO Technical,” which is based in Washington, D.C.

As there was no apparent published revenue procedure alerting the Determinations Unit to target either the tea party or even political cases broadly, if rules were being followed, that leaves special agency instructions coming from EO Technical in Washington to the Determinations Unit in Cincinnati as the sole possibility for why political cases were originally selected.

That is, if Lois Lerner was correct in her delivered testimony that her office had “not violated any IRS rules or regulations.”

To be fair, the rule does grant the Determinations Unit some discretion in determining which cases might be selected, but that too is limited to cases involving “an issue on which there is no published precedent, or there has been non-uniformity in the Service’s handling of similar cases, the organization may request that EO Determinations either refer the application to EO Technical or seek technical advice from EO Technical.”

The problem with this reading of the scandal is that the agency had already been processing the applications of 501(c)(4)s, which are allowed to engage in political activities, without putting them into a special category of cases. So, the Determinations Unit cannot claim that (c)(4)s engaging in political activity was unprecedented, because that is simply not true.

As for “non-uniformity” in the handling of political cases, that was created, not fixed, by the act of selecting certain political cases for special scrutiny and not all of them.

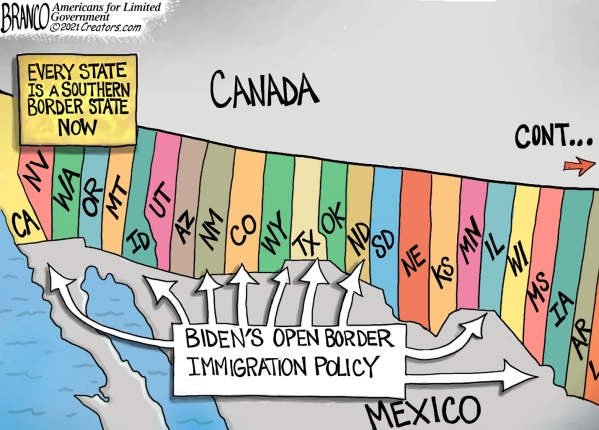

Apparently, it was not until after the Citizens United v. FEC Supreme Court ruling — which allowed non-profit organizations to make independent expenditures in favor or against candidates for elected office — that groups were targeted for engaging in political activities. But why?

That case said groups were protected under the First Amendment and allowed to act politically. Did either EO Technical or the Determinations Unit receive legal or other agency guidance that political cases needed to be targeted in light of the Citizens United ruling? If there was a smoking gun in this scandal, that would be it.

Leaving all that aside for a moment, even if Determinations Unit that came up with the idea of targeting political cases and/or the tea party for special scrutiny, then EO Technical in Washington, D.C. would still have had to approve the referral of political cases as a “designated category of cases,” which included the tea party groups.

There should also have been a form 3778 under Internal Revenue Manual 7.20.1.4.2 that was filed by the Determinations Unit to EO Technical requesting centralization of either tea party or political cases or just of one particular group. That is the form congressional investigators should be demanding. Allowing all of this correspondence to be bottled up with the Treasury Inspector General is unacceptable. Those records should be subpoenaed and made public.

If there was no form 3778 filed, then there may not be any evidence to support Miller’s sworn claim that “People in Cincinnati decided let’s start grouping these cases, let’s centralize these cases.” Then investigators would have to ask who at EO Technical might have requested the cases be centralized.

One final note. So far, congressional investigators have only focused on who came up with the idea of targeting the tea party, not on who decided that political cases ought to be broadly targeted in defiance of the Citizens United ruling.

This is a broader question, and if anyone wants an answer, they will have to in the least ask it — or else the true culprits in this scandal may never be revealed.

Because targeting speech on the basis that it is political is just as bad as targeting it because it’s “tea party” or “progressive” or religious for that matter. Viewpoint discrimination is viewpoint discrimination.

Robert Romano is the Senior Editor of Americans for Limited Government.