In 2009, when Pimco CEO and co-chief investment officer Mohamed El-Erian crafted the “new normal” hypothesis with colleagues, it anticipated “coming out of the financial crisis, the economy would not recover in a normal cyclical fashion,” and that “some of the recent abrupt changes to markets, households, institutions, and government policies are unlikely to be reversed in the next few years.”

Instead, “Global growth will be subdued for a while and unemployment high; a heavy hand of government will be evident in several sectors; the core of the global system will be less cohesive and, with the magnet of the Anglo-Saxon model in retreat, finance will no longer be accorded a preeminent role in post-industrial economies.”

Four years later, El-Erian’s words have proven prophetic. In the U.S. unemployment most certainly remains high at 7.6 percent — although beneath the numbers is even worse as it would be more like 11 percent if labor force participation had just held steady.

And growth is still lackluster. Just on June 26, the Bureau of Economic Analysis revised downward growth for the first quarter from 2.4 percent to 1.8 percent annualized on lower than anticipated consumer spending. So, that’s bad news, right?

Wrong. Stocks on the Dow Jones counterintuitively rallied by 254 points on June 26-27 over the two proceeding days of trading. Why?

Perhaps, to the perverse thinking of investors addicted to quantitative easing, bad economic news was actually good news. With Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke’s recent announcement of a sunset to his $85 billion a month quantitative easing when unemployment hits 7 percent — expected sometime in 2014 — markets tanked by more than 500 points.

Wall Street apparently prefers artificial monetary stimulus over real growth fundamentals.

So, if the economy is weaker than expected, then it will take longer for unemployment to reach 7 percent, therefore quantitative easing will last longer than expected, extending the program beyond the end of Bernanke’s term at the beginning of 2014. That gloomy outlook may have cheered investors.

And if things still look bad after Bernanke’s gone, it’s possible if not probable his successor will further extend the program.

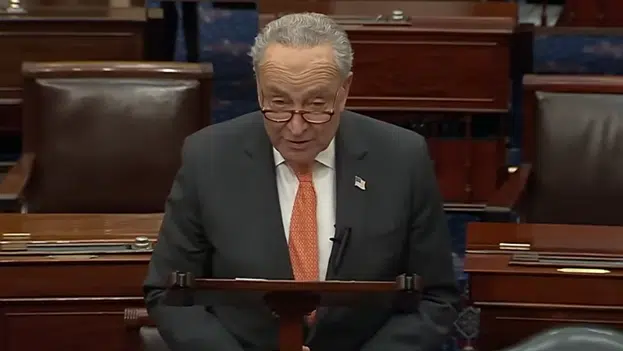

After all, the Fed head is a Senate-confirmed position, and the Senate will still be controlled by Democrats who, like their ideological leaders such as New York Times columnist and economist Paul Krugman, believe the stimulus was not big enough and has not lasted long enough.

As El-Erian predicted in 2009, “Farther down the road, political commitment will be needed to drain the system of emergency liquidity — a task complicated by the strong possibility that the U.S. and UK, in particular, will face a reduction in trend growth rates at a time of increasing pressure to lower unemployment. Remember, the evidence of recent years is that governments are reluctant to impose short-term pain for long-term gain.”

Therefore, political pressure will mount on whoever is nominated to be the next Fed chairman not to turn off the easy money, but to the contrary, to keep quantitative easing going.

A perfect example of the psychological impact of Bernanke’s announcement is the recent upswing in interest rates fostered by the Bernanke QE sunset announcement. Since then, mortgage applications — both for home sales and refis — have dropped off.

Suffice to say, any bad news in the housing sector — which was responsible for the financial crisis — will be joined by a chorus of voices in Washington, D.C. demanding yet more monetary easing from the central bank.

Even without any political pressure, the economic headwinds faced at present might compel the Fed to indefinitely extend the quantitative easing program anyway. Evidence continues to mount that China’s credit bubble is popping and its banking system is in big trouble. European financial markets remain as distressed as ever with deleveraging forces reasserting themselves.

Here, again, bad news might be more good news. For, stress in markets overseas in recent history has caused a flight to safety into treasuries, which has had the impact of lowering interest rates. That, coupled with a renewed Fed effort to pump more money into the economy, could mean a few more counterintuitive stock market rallies and further rate drops.

Taken together, it shows the perversity of the Fed’s program — and why it should come to an end sooner rather than later. For, the sooner the Fed gets out of the way, the sooner markets can really find their bottom and the virtuous cycle of growth can begin anew based on fundamentals instead of helicopter money.

After all, the new normal is bad enough. It need not be artificially prolonged.

Robert Romano is the Senior Editor of Americans for Limited Government.