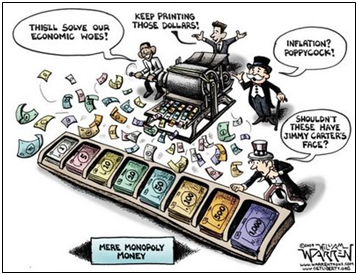

Since August 2007 when the financial crisis began, the U.S. Federal Reserve has increased its balance sheet more than 304 percent to $2.7 trillion, an unprecedented monetary expansion dubbed “quantitative easing.” In addition, it has lowered the Federal Funds Rate to near-zero levels to further ease credit.

When the central bank undertook these dramatic measures to expand the monetary base and lending, several observers, including this author, predicted that it would — indeed, should — have resulted in inflation, a general increase in price levels to correspond with the increase.

Yet, from 2008 through 2012, inflation for all items including food and energy has averaged just 2.08 percent. In 2013, if the first six months are any indication, inflation will come in at a tame 2.2 percent for the year.

The question is why? How is it that the Fed’s balance sheet has increased on average 33 percent a year, but inflation only registers 2 percent?

“[I]nflation has been postponed,” writes University Professor of Public Policy at Carnegie Mellon University Allan Meltzer in his post, “When inflation doves cry.”

Part of the reason is because most of the quantitative easing has not been converted into lending. Since 2007, excess reserves held by banks have jumped from a mere $1.78 billion —with a “b” — to more than $2.03 trillion with a “t” today.

Meltzer notes, “all the reserves added in the second and third rounds of QE, more than 95 percent, are sitting in excess reserves, neither lent nor borrowed and never used to increase money in circulation. The Fed pays the banks 0.25 percent to keep them idle.”

This can be seen as the $56 trillion of credit outstanding nationwide — all debts public and private — has remained essentially frozen for five years, only growing at about 2 percent a year. Between 1946 and 2007, it averaged 8.4 percent growth annually.

Or M2, which has only averaged 6.9 percent average since 2008 despite the rapid acceleration of Fed assets.

All of which indicates a very weak recovery, particularly in the financial sector — and explains why the money is just sitting there. Demand for loans is weak, so the money supply is not accelerating.

Instead, banks have even found a way to profit off the idle reserves, by earning interest on them from the Fed: “With $2 trillion in excess reserves, and the prospect of as much as $85 billion added each month, banks receive $5 billion a year, and rising, without taking any risk.”

But, Meltzer warns inflation may yet be on the horizon, “Historically, the Fed has typically been slow to respond to inflation. Waiting until inflation is here, as some propose, is the usual way. But that merely fuels inflation expectations and makes the task more painful.”

Perhaps then the thing to look for is an acceleration in credit creation, and a drawdown of the excess reserves by the banks. The quantitative easing has not really entered the economy yet, so why should it have caused inflation? The question is: When will it enter the economy?

After all, as I wrote back in 2009, “the prediction is not for instant inflation, but that once market-based thawing does apparently begin to ensue, and all the excessive liquidity finds its way into the marketplace, demand will spike in one area or another and thus so will prices. There will be another asset bubble. And then the politicians will dutifully declare that the ‘recovery’ has ensued.”

Certainly, the recovery has not fully happened yet, and until it does, the excess liquidity will lay dormant. But it may just be a matter of time.

Robert Romano is the Senior Editor of Americans for Limited Government.